Ngô Đình Diệm was a South Vietnamese politician who was the final prime minister of the State of Vietnam (1954–1955) and later the first president of the Republic of Vietnam from 1955 until his capture and assassination during the CIA-backed 1963 South Vietnamese coup.

The Viet Cong (VC) was an epithet and umbrella term to refer to the communist-driven armed movement and united front organization in South Vietnam. Formally organized as and led by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam and nominally conducted military operations under the name of the Liberation Army of South Vietnam (LASV), the movement fought under the direction of North Vietnam against the South Vietnamese and United States governments during the Vietnam War. The organization had both guerrilla and regular army units, as well as a network of cadres who organized and mobilized peasants in the territory the VC controlled. During the war, communist fighters and some anti-war activists claimed that the VC was an insurgency indigenous to the South that represented the legitimate rights of people in South Vietnam, while the U.S. and South Vietnamese governments portrayed the group as a tool of North Vietnam. It was later conceded by the modern Vietnamese communist leadership that the movement was actually under the North Vietnamese political and military leadership, aiming to unify Vietnam under a single banner.

Dương Văn Minh, popularly known as Big Minh, was a South Vietnamese politician and a senior general in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and a politician during the presidency of Ngô Đình Diệm. In 1963, he became chief of a military junta after leading a coup in which Diệm was assassinated. Minh lasted only three months before being toppled by Nguyễn Khánh, but assumed power again as the fourth and last President of South Vietnam in April 1975, two days before surrendering to North Vietnamese forces. He earned his nickname "Big Minh", because he was approximately 1.83 m (6 ft) tall and weighed 90 kg (198 lb).

Hòa Hảo is a Vietnamese new religious movement. It is described either as a syncretistic folk religion or as a sect of Buddhism. It was founded in 1939 by Huỳnh Phú Sổ (1920–1947), who is regarded as a saint by its devotees. It is one of the major religions of Vietnam with between one million and eight million adherents, mostly in the Mekong Delta.

A Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) is a designation for a group of United States military advisors sent to other countries to assist in the training of conventional armed forces and facilitate military aid. Although numerous MAAGs operated around the world throughout the 1940s–1970s, including in Yugoslavia after 1951, and to the Ethiopian Armed Forces, the most famous MAAGs were those active in South Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand, before and during the Vietnam War. Records held by the National Archives and Records Administration detail the activities of numerous assistance advisory groups.

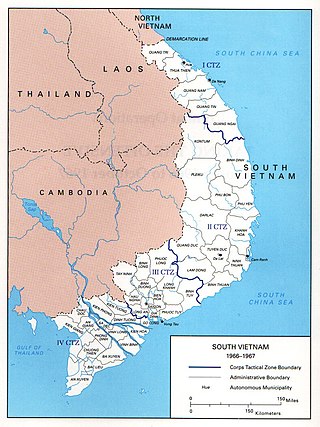

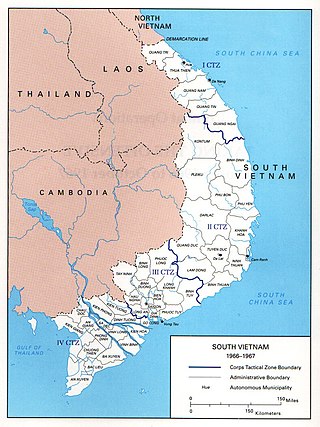

The Battle of Bình Giã was conducted by the Viet Cong (VC) and People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) from December 28, 1964, to January 1, 1965, during the Vietnam War in Bình Giã, Phước Tuy province, South Vietnam.

On November 11, 1960, a failed coup attempt against President Ngô Đình Diệm of South Vietnam was led by Lieutenant Colonel Vương Văn Đông and Colonel Nguyễn Chánh Thi of the Airborne Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN).

Phạm Ngọc Thảo, also known as Albert Thảo, was a communist sleeper agent of the Việt Minh who infiltrated the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and also became a major provincial leader in South Vietnam. In 1962, he was made overseer of Ngô Đình Nhu's Strategic Hamlet Program in South Vietnam and deliberately forced it forward at an unsustainable speed, causing the production of poorly equipped and poorly defended villages and the growth of rural resentment toward the regime of President Ngô Đình Diệm, Nhu's elder brother. In light of the failed land reform efforts in North Vietnam, the Hanoi government welcomed Thao's efforts to undermine Diem.

The South Vietnamese Regional Forces, originally the Civil Guard, were a component of Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) territorial defence forces. Recruited locally, they served as full-time province-level forces, originally raised as a militia. In 1964, the Regional Forces were integrated into the ARVN and placed under the command of the Joint General Staff.

The McNamara–Taylor mission was a 10-day fact-finding expedition to South Vietnam in September 1963 by the Kennedy administration to review progress in the battle by the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and its American advisers against the communist insurgency of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. The mission was led by US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and General Maxwell D. Taylor, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

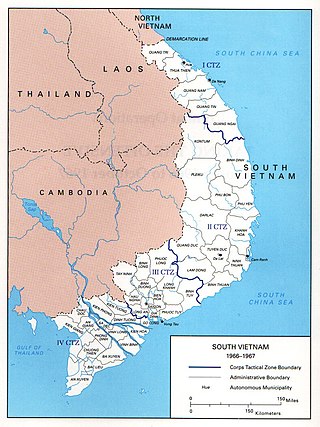

The 1954 to 1959 phase of the Vietnam War was the era of the two nations. Coming after the First Indochina War, this period resulted in the military defeat of the French, a 1954 Geneva meeting that partitioned Vietnam into North and South, and the French withdrawal from Vietnam, leaving the Republic of Vietnam regime fighting a communist insurgency with USA aid. During this period, North Vietnam recovered from the wounds of war, rebuilt nationally, and accrued to prepare for the anticipated war. In South Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm consolidated power and encouraged anti-communism. This period was marked by U.S. support to South Vietnam before Gulf of Tonkin, as well as communist infrastructure-building.

The 1959 to 1963 phase of the Vietnam War started after the North Vietnamese had made a firm decision to commit to a military intervention in the guerrilla war in the South Vietnam, a buildup phase began, between the 1959 North Vietnamese decision and the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which led to a major US escalation of its involvement. Vietnamese communists saw this as a second phase of their revolution, the US now substituting for the French.

The year 1961 saw a new American president, John F. Kennedy, attempt to cope with a deteriorating military and political situation in South Vietnam. The Viet Cong (VC) with assistance from North Vietnam made substantial gains in controlling much of the rural population of South Vietnam. Kennedy expanded military aid to the government of President Ngô Đình Diệm, increased the number of U.S. military advisors in South Vietnam, and reduced the pressure that had been exerted on Diệm during the Eisenhower Administration to reform his government and broaden his political base.

The defeat of the South Vietnamese Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) in a battle in January set off a furious debate in the United States on the progress being made in the war against the Viet Cong (VC) in South Vietnam. Assessments of the war flowing into the higher levels of the U.S. government in Washington, D.C. were wildly inconsistent, some citing an early victory over the VC, others a rapidly deteriorating military situation. Some senior U.S. military officers and White House officials were optimistic; civilians of the Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), junior military officers, and the media were decidedly less so. Near the end of the year, U.S. leaders became more pessimistic about progress in the war.

The Viet Cong (VC) insurgency expanded in South Vietnam in 1962. U.S. military personnel flew combat missions and accompanied South Vietnamese soldiers in ground operations to find and defeat the insurgents. Secrecy was the official U.S. policy concerning the extent of U.S. military involvement in South Vietnam. The commander of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), General Paul D. Harkins, projected optimism that progress was being made in the war, but that optimism was refuted by the concerns expressed by a large number of more junior officers and civilians. Several prominent magazines, newspapers and politicians in the U.S. questioned the military strategy the U.S. was pursuing in support of the South Vietnamese government of President Ngô Đình Diệm. Diệm created the Strategic Hamlet Program as his top priority to defeat the VC. The program intended to cluster South Vietnam's rural dwellers into defended villages where they would be provided with government social services.

In 1960, the oft-expressed optimism of the United States and the Government of South Vietnam that the Viet Cong (VC) were nearly defeated proved mistaken. Instead the VC became a growing threat and security forces attempted to cope with VC attacks, assassinations of local officials, and efforts to control villages and rural areas. Throughout the year, the U.S. struggled with the reality that much of the training it had provided to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) during the previous five years had not been relevant to combating an insurgency. The U.S. changed its policy to allow the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) to begin providing anti-guerrilla training to ARVN and the paramilitary Civil Guard.

1959 saw Vietnam still divided into South and North. North Vietnam authorized the Viet Cong (VC) to undertake limited military action as well as political action to subvert the Diệm government. North Vietnam also authorized the construction of what would become known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail to supply the VC in South Vietnam. Armed encounters between the VC and the government of South Vietnam became more frequent and with larger numbers involved. In September, 360 soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) were ambushed by a force of about 100 VC guerrillas.

In 1955, the Prime Minister of South Vietnam Ngô Đình Diệm faced a severe challenge to his rule over South Vietnam from the Bình Xuyên criminal gang and the Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo religious sects. In the Battle of Saigon in April, Diệm's army eliminated the Bình Xuyên as a rival and soon also reduced the power of the sects. The United States, which had been wavering in its support of Diệm before the battle, strongly supported him afterwards. Diệm declined to enter into talks with North Vietnam concerning an election in 1956 to unify the country. Diệm called a national election in October and easily defeated Head of State Bảo Đại, thus becoming President of South Vietnam.

Ngo Dinh Diem consolidated his power as the President of South Vietnam. He declined to have a national election to unify the country as called for in the Geneva Accords. In North Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh apologized for certain consequences of the land reform program he had initiated in 1955. The several thousand Viet Minh cadres the North had left behind in South Vietnam focused on political action rather than insurgency. The South Vietnamese army attempted to root out the Viet Minh.

In 1957 South Vietnam's President Ngô Đình Diệm visited the United States and was acclaimed a "miracle man' who had saved one-half of Vietnam from communism. However, in the latter part of the year, violent incidents committed by anti-Diệm insurgents increased and doubts about the viability of Diệm's government were expressed in the media and by U.S. government officials.