Hitoyoshi is a city in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. As of 31 August 2024, the city had an estimated population of 29,842 in 15292 households, and a population density of 140 persons per km2. The total area of the city is 210.55 km2 (81.29 sq mi).

Ashikita is a town located in Ashikita District, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan.As of 1 August 2024, the town had an estimated population of 15,024 in 6909 households, and a population density of 64 persons per km2. The total area of the town is 34.08 km2 (13.16 sq mi).

Itsuki is a village located in Kuma District, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. As of 31 August 2024, the village had an estimated population of 937 in 466 households, and a population density of 3.7 persons per km2. The total area of the village is 252.92 km2 (97.65 sq mi). The name of Itsuki is well known for an indigenous folksong Itsuki no Komoriuta, or Lullaby of Itsuki.

The Kuma River is a river in Kumamoto Prefecture, central Western part of Kyūshū, Japan. It is sometimes referred as Kumagawa River. It is the longest river in Kyushu, with the length of 115 km long and has a drainage area of 1,880 km2 (730 sq mi). The river's estuary was designated part of Japan's 500 Important Wetlands.

The Hisatsu Line is a railway line in Kyushu, Japan, operated by the Kyushu Railway Company. It connects Yatsushiro on the Kagoshima Main Line to Hayato station, Kirishima on the Nippo Main Line. From 1909 the line was the original rail connection from Yatsushiro to Kagoshima until the Yatsushiro – Kagoshima coastal route via Sendai opened in 1927.

The Yunomae Line is a railway line in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan, connecting Hitoyoshi-Onsen Station in Hitoyoshi and Yunomae Station in Yunomae. It is the only railway line operated by the third sector Kumagawa Railroad. As the company name suggests, the line parallels the Kuma River. The company is also called Kumatetsu (くま鉄). The company took over the former JR Kyushu line in 1989.

Yatsushiro Station is a junction passenger railway station located in the city of Yatsushiro, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. It is operated by JR Kyushu and the third-sector railway company Hisatsu Orange Railway. It is also a freight depot for the Japan Freight Railway Company.

Aoi Aso Shrine is a Shinto shrine in Hitoyoshi, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. It is colloquially known as Aoi-san (青井さん). It was originally established as a prefectural shrine, but is currently designated as a national shrine. Five of the structures within the shrine are listed as National Treasures of Japan.

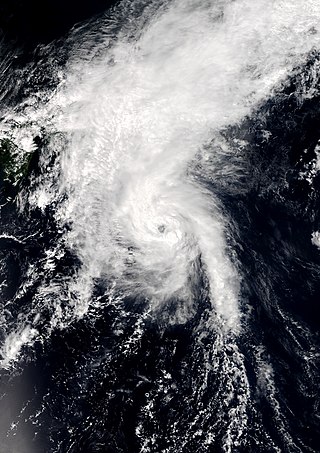

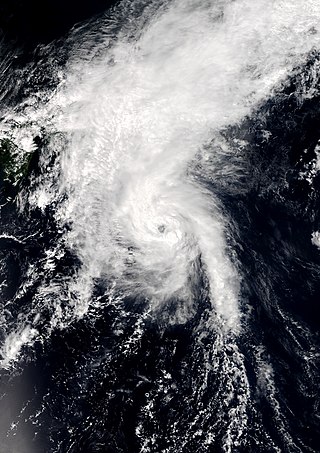

Tropical Storm Etau was the deadliest tropical cyclone to impact Japan since Typhoon Tokage in 2004. Forming on August 8, 2009 from an area of low pressure, the system gradually intensified into a tropical storm. Tracking in a curved path around the edge of a subtropical ridge, Etau continued to intensify as it neared Japan. By August 10, the cyclone reached its peak intensity as a weak tropical storm with winds of 75 km/h and a barometric pressure of 992 hPa (mbar). Shortly after, Etau began to weaken. Increasing wind shear led to the center becoming devoid of convection and the system eventually weakened to a tropical depression on August 13. The remnants of Etau persisted for nearly three days before dissipating early on August 16.

Typhoon Man-yi was a very severe storm that brought very strong winds and flash floods to Japan during mid-September. The third typhoon of the 2013 Pacific typhoon season, Man-yi was identified on September 10. It became a storm on September 12 and reached peak intensity on September 15. Japan was then experiencing winds above 30 knots. Typhoon Man-yi became extratropical on September 16 and fully dissipated late on September 20 in the Kamchatka Peninsula region, bringing strong winds until September 25.

Severe Tropical Storm Nakri, known in the Philippines as Tropical Storm Inday, was a large, long-lived, and slow-moving tropical cyclone that produced prolific rains over Japan and South Korea in early August 2014.

Severe Tropical Storm Etau caused extensive and destructive flooding across eastern Japan during early September 2015. Originating from a tropical disturbance near Guam on September 2, Etau was first classified a tropical depression on September 5. Tracking generally north, the cyclone gradually intensified and reached its peak strength with winds of 95 km/h (60 mph) on September 8. The following day, Etau made landfall in Honshu, Japan. It subsequently transitioned into an extratropical cyclone later that day over the Sea of Japan.

Hitoyoshi Castle was an Edo period flatlands-style Japanese castle located in the city of Hitoyoshi, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. Its ruins have been protected as a National Historic Site since 1961. It is No.93 on the list "100 Fine Castles of Japan". Since the Sagara clan was appointed jitō n the Kamakura period, the clan inhabited this castle for 35 generations, for 670 years until the Meiji restoration of 1871.

Kawasemi Yamasemi is a two-car limited express train operated by Kyushu Railway Company in Japan.

Severe Tropical Storm Nanmadol, known in the Philippines as Severe Tropical Storm Emong, was a tropical cyclone that impacted southern Japan during July 2017. Nanmadol developed over in the Philippine Sea as a tropical depression on July 1, and strengthened into the third named storm of the 2017 typhoon season on July 3. After gaining organization, the system rapidly developed and intensified into a severe tropical storm and reached its peak intensity with a 10-minute maximum sustained winds of 100 km/h (62 mph) and a minimum barometric pressure of 985 hPa (29.1 inHg). On July 4, Nanmadol turned eastwards and made landfall near Nagasaki, Kyushu, just before it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.

In late June through mid-July 2018, successive heavy downpours in southwestern Japan resulted in widespread, devastating floods and mudflows. The event is officially referred to as Heisei san-jū-nen shichi-gatsu gōu by the Japan Meteorological Agency. As of 20 July, 225 people were confirmed dead across 15 prefectures with a further 13 people reported missing. More than 8 million people were advised or urged to evacuate across 23 prefectures. It is the deadliest freshwater flood-related disaster in the country since the 1982 Nagasaki flood when 299 people died.

The SL Hitoyoshi was a named steam hauled excursion train operated by the Kyushu Railway Company on the Kagoshima Main Line and the Hisatsu Line between April 2009 and March 2024.

Typhoon Talim, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Lannie, was an intense and destructive tropical cyclone that affected parts of East Asia, especially Japan, during September 2017. The eighteenth named storm and the sixth typhoon of the 2017 Pacific typhoon season, Talim's origins can be traced back to an area of low-pressure that the Joint Typhoon Warning Center first monitored on September 6. The disturbance was upgraded to a tropical depression by the Japan Meteorological Agency only two days later, and it became a tropical storm on September 9, earning the name Talim. Talim grew stronger over the next few days, eventually becoming a typhoon the next day. Within a favorable environment, the typhoon rapidly intensified after passing through the Ryukyu Islands. However, as it moved eastward, Talim started to weaken due to wind shear, and on September 16, it was downgraded to a tropical storm. The storm passed over Japan, near Kyushu the next day, before becoming extratropical on September 18. The extratropical remnants were last noted by the JMA four days later, before dissipating fully on September 22.

On 5 May 2023, a MJMA 6.5 or Mw 6.3 earthquake struck off the coast of Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. It was located 49 kilometres northeast of Anamizu, Hōsu District, with the town of Suzu closest to the epicenter.

The 1957 Isahaya flood was a series of floods occurring in the northwest part of the Japanese island of Kyushu, in and around Isahaya, Nagasaki Prefecture. Spanning 3 days, from July 25 to July 28, 1957, torrential rain brought floods and landslides to the region. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries recorded an astonishing 1.109 meters of rain in just one 24-hour period, the highest ever recorded in Japan.