Related Research Articles

Abortion in Canada is legal throughout pregnancy, and is publicly funded as a medical procedure under the combined effects of the federal Canada Health Act and provincial health-care systems. However, access to services and resources varies by region. While some restrictions exist, Canada is one of the few nations with no criminal restrictions on abortion. Abortion is subject to provincial healthcare regulatory rules and guidelines for physicians. No provinces offer abortion on request at 24 weeks and beyond, although there are exceptions for certain medical complications.

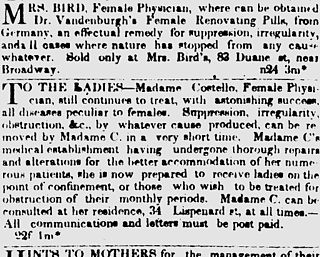

Emily Howard Stowe was a Canadian physician who was the first female physician to practise in Canada, the second licensed female physician in Canada and an activist for women's rights and suffrage. Stowe helped found the women's suffrage movement in Canada and campaigned for the country's first medical college for women.

John Bodkin Adams was a British general practitioner, convicted fraudster, and suspected serial killer. Between 1946 and 1956, 163 of his patients died while in comas, which was deemed to be worthy of investigation. In addition, 132 out of 310 patients had left Adams money or items in their wills.

Thomas Neill Cream, also known as the Lambeth Poisoner, was a Scottish-Canadian medical doctor and serial killer who poisoned his victims with strychnine. He murdered up to 10 people in three countries, targeting mostly lower-class women, prostitutes and pregnant women seeking abortions. He was convicted and sentenced to death, and was hanged on 15 November 1892.

The practice of induced abortion—the deliberate termination of a pregnancy—has been known since ancient times. Various methods have been used to perform or attempt abortion, including the administration of abortifacient herbs, the use of sharpened implements, the application of abdominal pressure, and other techniques. The term abortion, or more precisely spontaneous abortion, is sometimes used to refer to a naturally occurring condition that ends a pregnancy, that is, to what is popularly called a miscarriage. But in what follows the term abortion will always refer to an induced abortion.

R v Davidson, also known as the Menhennitt ruling, was a significant ruling delivered in the Supreme Court of Victoria on 26 May 1969. It concerned the legality of abortion in the Australian state of Victoria. The ruling was not the end of the case, but rather answered certain questions of law about the admissibility of evidence, so as to allow the trial to proceed.

R v Adams [1957] is an English case that established the principle of double effect applicable to doctors: that if a doctor "gave treatment to a seriously ill patient with the aim of relieving pain or distress, as a result of which that person's life was inadvertently shortened, the doctor was not guilty of murder" where a restoration to health is no longer possible. Such medicines are among those sometimes used in palliative care, most commonly for the most severe pain.

New York State Department of Health Code, Section 405, also known as the Libby Zion Law, is a regulation that limits the amount of resident physicians' work in New York State hospitals to roughly 80 hours per week. The law was named after Libby Zion, who died in 1984 at the age of 18 under the care of what her father believed to be overworked resident physicians and intern physicians. In July 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education adopted similar regulations for all accredited medical training institutions in the United States.

Milan Vuitch was a physician performing abortions in Washington, D.C., and Silver Spring, Maryland. Born in Serbia, he was a naturalized U.S. citizen.

Gertrude "Bobby" Hullett, a resident of Eastbourne, East Sussex, England, was a patient of Dr John Bodkin Adams, who was indicted for her murder but not brought to trial for it. Adams was tried in 1957 for the murder of Edith Alice Morrell, and the prosecution intended to proceed with the Hullett indictment as a second prosecution that could follow the Morrell case in certain circumstances, although it did not bring the case to trial following the verdict in the Morrell trial.

Edith Alice Morrell was a resident of Eastbourne, East Sussex, England, and patient of Dr John Bodkin Adams. Although Adams was acquitted in 1957 of her murder, the question of Adams' role in Morrell's death excited considerable interest at the time and continues to do so. This is partly because of negative pre-trial publicity which remains in the public record, partly because of the several dramatic incidents in the trial and partly as Adams declined to give evidence in his own defence. The trial featured in headlines around the world and was described at the time as "one of the greatest murder trials of all time" and "murder trial of the century". It was also described by the trial judge as unique because "the act of murder" had "to be proved by expert evidence." The trial also established the legal doctrine of double effect, where a doctor giving treatment with the aim of relieving pain may, as an unintentional result, shorten life.

Henry Dyer Grindle was a Manhattan physician and abortion provider in the 1870s who worked under the name H.D. Grindle.

Nelson Gordon Bigelow was a Canadian lawyer and political figure in Ontario. He represented Toronto in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario as a Liberal in 1892.

Ann Augusta Stowe-Gullen, was a Canadian medical doctor, lecturer and suffragist. She was born in Mount Pleasant, Ontario as the daughter of Emily Howard Stowe and John Fiuscia Michael Heward Stowe. A plaque regarding her work can be found in Brant County, Ontario.

Kermit Barron Gosnell is an American former physician and serial killer. He provided abortions at his clinic in West Philadelphia. Gosnell was convicted of the murders of three infants who were born alive after using drugs to induce birth, the manslaughter of one woman during an abortion procedure, and of several other medically related crimes.

Conrad Robert Murray is a Grenadian-American former cardiologist who was the personal physician of Michael Jackson, providing medical treatment to help him sleep on the day Jackson died in 2009. In 2011, Murray was convicted of involuntary manslaughter in Jackson's death for having inadvertently overdosed him with a powerful surgical anesthetic, propofol, which was being improperly used as a bedtime sleep agent. Murray served a little less than two years out of his original four-year prison sentence.

People v. Murray was the American criminal trial of Michael Jackson's personal physician, Conrad Murray, who was charged with involuntary manslaughter for the pop singer's death on June 25, 2009, from a dose of the general anesthetic propofol. The trial, which started on September 27, 2011, was held in the Los Angeles County Superior Court in Los Angeles, California, before Judge Michael Pastor as a televised proceeding, reaching a guilty verdict on November 7, 2011.

Constance Barbara Backhouse, is a Canadian legal scholar and historian, specializing in gender and race discrimination. She is a Distinguished University Professor and University Research Chair at the Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa in Ottawa, Canada. In addition to her academic publications, Backhouse is the author of several books on feminist- and race-related legal rights topics. Backhouse is President of the American Society for Legal History, and is the first non-US scholar to hold this position.

Sheila Hodgers was an Irish woman from Dundalk, County Louth, who died of multiple cancers two days after giving birth to her third child. She was denied treatments for her cancer while pregnant because the Catholic ethos of the hospital did not wish to harm the foetus. Her case was publicised in an article in The Irish Times the week before a September 1983 referendum which enshrined the right to life of the foetus in the Constitution of Ireland. The case has been recounted in subsequent pro-choice commentary on abortion in the Republic of Ireland.

William Scott Husel is an American intensive/critical care physician who was charged with 14 counts of murder relating to the deaths of multiple patients from his care of terminally ill patients at Mount Carmel West and St. Ann's Hospitals in Columbus, Ohio. The prosecution in this case argued that Dr. Husel hastened the death of terminally ill patients. He turned himself in on June 5, 2019. After an extensive trial, Husel was found not guilty on all counts on April 20, 2022.

References

- Constance B. Backhouse, "The Celebrated Abortion Trial of Dr. Emily Stowe, Toronto, 1879," Canadian Bulletin of Medical History/Bulletin canadien d'histoire de la médecine, Volume 8: 1991, pages 159-187.

- Famous Canadian Physicians: Dr. Emily Howard Stowe at Library and Archives Canada