| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɒksɪˈtoʊsɪn/ ⓘ OK-sih-TOH-sin |

| Trade names | Induxin |

| ATC code | |

| Physiological data | |

| Source tissues | Pituitary gland |

| Target tissues | Wide spread |

| Receptors | Oxytocin receptor |

| Antagonists | Atosiban |

| Precursor | Oxytocin/neurophysin I prepropeptide |

| Metabolism | Liver and other oxytocinases |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 30% |

| Metabolism | Liver and other oxytocinases |

| Elimination half-life | 1–6 min (IV) ~2 h (intranasal) [1] [2] |

| Excretion | Biliary and kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.045 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

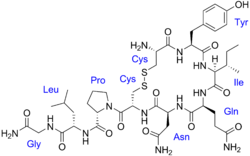

| Formula | C43H66N12O12S2 |

| Molar mass | 1007.19 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Oxytocin is a peptide hormone and neuropeptide normally produced in the hypothalamus and released by the posterior pituitary. [3] Present in animals since early stages of evolution, in humans it plays roles in behavior that include social bonding, love, reproduction, childbirth, and the period after childbirth. [4] [5] [6] [7] Oxytocin is released into the bloodstream as a hormone in response to sexual activity and during childbirth. [8] [9] It is also available in pharmaceutical form. In either form, oxytocin stimulates uterine contractions to speed up the process of childbirth.

Contents

- Etymology

- History

- Biochemistry

- Biosynthesis

- Neural sources

- Non-neural sources

- Evolution

- Biological function

- Physiological

- Psychological

- Chemistry

- In medicine

- See also

- References

- Further reading

- External links

In its natural form, it also plays a role in maternal bonding and milk production. [9] [10] Production and secretion of oxytocin is controlled by a positive feedback mechanism, where its initial release stimulates production and release of further oxytocin. For example, when oxytocin is released during a contraction of the uterus at the start of childbirth, this stimulates production and release of more oxytocin and an increase in the intensity and frequency of contractions. This process compounds in intensity and frequency and continues until the triggering activity ceases. A similar process takes place during lactation and during sexual activity.

Oxytocin is derived by enzymatic splitting from the peptide precursor encoded by the human OXT gene. The deduced structure of the active nonapeptide is: