Mathematics

5 is a Fermat prime, a Mersenne prime exponent, [1] as well as a Fibonacci number. 5 is the first congruent number, as well as the length of the hypotenuse of the smallest integer-sided right triangle, making part of the smallest Pythagorean triple (3, 4, 5). [2]

5 is the first safe prime [3] and the first good prime. [4] 11 forms the first pair of sexy primes with 5. [5] 5 is the second Fermat prime, of a total of five known Fermat primes. [6] 5 is also the first of three known Wilson primes (5, 13, 563). [7]

Geometry

A shape with five sides is called a pentagon. The equilateral pentagon is the first regular polygon that does not tile the plane with copies of itself. The pentagon solid has the largest face of any of the five regular three-dimensional regular Platonic solids.

A conic is determined using five points in the same way that two points are needed to determine a line. [8] A pentagram, or five-pointed polygram, is a star polygon constructed by connecting some non-adjacent vertices of a regular pentagon as self-intersecting edges. [9] The internal geometry of the pentagon and pentagram (represented by its Schläfli symbol {5/2}) appears prominently in Penrose tilings. Pentagrams are facets inside Kepler–Poinsot star polyhedra and Schläfli–Hess star polychora.

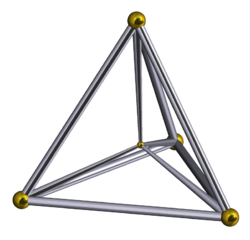

There are five regular Platonic solids the tetrahedron, the cube, the octahedron, the dodecahedron, and the icosahedron. [10]

The plane contains a total of five Bravais lattices, or arrays of points defined by discrete translation operations. Uniform tilings of the plane, are generated from combinations of only five regular polygons. [11]

Higher dimensional geometry

A hypertetrahedron, or 5-cell, is the 4 dimensional analogue of the tetrahedron. It has five vertices. Its orthographic projection is homomorphic to the group K5. [12] : p.120

There are five fundamental mirror symmetry point group families in 4-dimensions. There are also 5 compact hyperbolic Coxeter groups, or 4-prisms, of rank 5, each generating uniform honeycombs in hyperbolic 4-space as permutations of rings of the Coxeter diagrams. [13]

Algebra

5 is the value of the central cell of the first non-trivial normal magic square, called the Luoshu square. All integers can be expressed as the sum of five non-zero squares. [14] [15] There are five countably infinite Ramsey classes of permutations. [16] : p.4 5 is conjectured to be the only odd, untouchable number; if this is the case, then five will be the only odd prime number that is not the base of an aliquot tree. [17]

).

). Every odd number greater than five is conjectured to be expressible as the sum of three prime numbers; Helfgott has provided a proof of this [18] (also known as the odd Goldbach conjecture) that is already widely acknowledged by mathematicians as it still undergoes peer-review. On the other hand, every odd number greater than one is the sum of at most five prime numbers (as a lower limit). [19]

Group theory

In graph theory, all graphs with four or fewer vertices are planar, however, there is a graph with five vertices that is not: K5, the complete graph with five vertices. By Kuratowski's theorem, a finite graph is planar if and only if it does not contain a subgraph that is a subdivision of K5, or K3,3, the utility graph. [20]

There are five complex exceptional Lie algebras. The five Mathieu groups constitute the first generation in the happy family of sporadic groups. These are also the first five sporadic groups to have been described. [21] : p.54 A centralizer of an element of order 5 inside the largest sporadic group arises from the product between Harada–Norton sporadic group and a group of order 5. [22] [23]