| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dogmatil, Others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets, capsules, solution), intramuscular injection |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 25–40% [2] [3] |

| Protein binding | <40% [2] |

| Metabolism | Not metabolized; [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] 95% is exerted as the unchanged drug [2] [4] |

| Elimination half-life | 6–8 hours [2] [9] |

| Excretion | Urine (70–90%), [9] [3] Feces. [4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.036.124 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

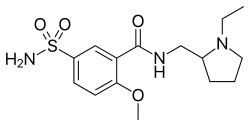

| Formula | C15H23N3O4S |

| Molar mass | 341.43 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Sulpiride, sold under the brand name Dogmatil among others, is an atypical antipsychotic (although some texts have referred to it as a typical antipsychotic) [10] medication of the benzamide class which is used mainly in the treatment of psychosis associated with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, and is sometimes used in low dosage to treat anxiety and dysthymia.

Contents

- Medical uses

- Schizophrenia

- Depression and anxiety

- Other uses

- Contraindications

- Pregnancy and lactation

- Side effects

- Overdose

- Interactions

- Pharmacology

- Pharmacodynamics

- History

- Society and culture

- Brand names

- Medicinal forms

- Patient aversions

- Research

- Hormonal contraception

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- References

- External links

The drug is chemically and clinically similar to amisulpride. Levosulpiride is its purified levo-isomer and is sold in some countries for similar purposes.

Sulpiride is commonly used in Asia, Central America, Europe, South Africa and South America. It is not approved in the United States, Canada, or Australia.