Antipsychotics, also known as neuroleptics, are a class of psychotropic medication primarily used to manage psychosis, principally in schizophrenia but also in a range of other psychotic disorders. They are also the mainstay together with mood stabilizers in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare but life-threatening reaction that can occur in response to neuroleptic or antipsychotic medication. Symptoms include high fever, confusion, rigid muscles, variable blood pressure, sweating, and fast heart rate. Complications may include rhabdomyolysis, high blood potassium, kidney failure, or seizures.

The atypical antipsychotics (AAP), also known as second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and serotonin–dopamine antagonists (SDAs), are a group of antipsychotic drugs largely introduced after the 1970s and used to treat psychiatric conditions. Some atypical antipsychotics have received regulatory approval for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, irritability in autism, and as an adjunct in major depressive disorder.

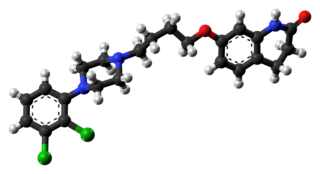

Quetiapine, sold under the brand name Seroquel among others, is an atypical antipsychotic medication used for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and major depressive disorder. Despite being widely used as a sleep aid due to its sedating effect, the benefits of such use do not appear to generally outweigh the side effects. It is taken orally.

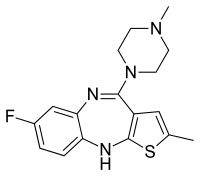

Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic primarily used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. For schizophrenia, it can be used for both new-onset disease and long-term maintenance. It is taken by mouth or by injection into a muscle.

Aripiprazole, sold under the brand names Abilify and Aristada, among others, is an atypical antipsychotic. It is primarily used in the treatment of schizophrenia, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and bipolar disorder; other uses include as an add-on treatment in major depressive disorder, tic disorders, and irritability associated with autism. Aripiprazole is taken by mouth or via injection into a muscle. A Cochrane review found low-quality evidence of effectiveness in treating schizophrenia.

Dopaminergic means "related to dopamine" (literally, "working on dopamine"), dopamine being a common neurotransmitter. Dopaminergic substances or actions increase dopamine-related activity in the brain. Dopaminergic brain pathways facilitate dopamine-related activity. For example, certain proteins such as the dopamine transporter (DAT), vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), and dopamine receptors can be classified as dopaminergic, and neurons that synthesize or contain dopamine and synapses with dopamine receptors in them may also be labeled as dopaminergic. Enzymes that regulate the biosynthesis or metabolism of dopamine such as aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase or DOPA decarboxylase, monoamine oxidase (MAO), and catechol O-methyl transferase (COMT) may be referred to as dopaminergic as well. Also, any endogenous or exogenous chemical substance that acts to affect dopamine receptors or dopamine release through indirect actions (for example, on neurons that synapse onto neurons that release dopamine or express dopamine receptors) can also be said to have dopaminergic effects, two prominent examples being opioids, which enhance dopamine release indirectly in the reward pathways, and some substituted amphetamines, which enhance dopamine release directly by binding to and inhibiting VMAT2.

Amisulpride is an antiemetic and antipsychotic medication used at lower doses intravenously to prevent and treat postoperative nausea and vomiting; and at higher doses by mouth to treat schizophrenia and acute psychotic episodes. It is sold under the brand names Barhemsys and Solian, Socian, Deniban and others. At very low doses it is also used to treat dysthymia.

Sulpiride, sold under the brand name Dogmatil among others, is an atypical antipsychotic medication of the benzamide class which is used mainly in the treatment of psychosis associated with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, and sometimes used in low dosage to treat anxiety and mild depression. Sulpiride is commonly used in Asia, Central America, Europe, South Africa and South America. Levosulpiride is its purified levo-isomer and is sold in India for similar purpose. It is not approved in the United States, Canada, or Australia. The drug is chemically and clinically similar to amisulpride.

Zotepine is an atypical antipsychotic drug indicated for acute and chronic schizophrenia. It has been used in Germany since 1990 and Japan since 1982.

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) are symptoms that are archetypically associated with the extrapyramidal system of the brain's cerebral cortex. When such symptoms are caused by medications or other drugs, they are also known as extrapyramidal side effects (EPSE). The symptoms can be acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term). They include movement dysfunction such as dystonia, akathisia, parkinsonism characteristic symptoms such as rigidity, bradykinesia, tremor, and tardive dyskinesia. Extrapyramidal symptoms are a reason why subjects drop out of clinical trials of antipsychotics; of the 213 (14.6%) subjects that dropped out of one of the largest clinical trials of antipsychotics, 58 (27.2%) of those discontinuations were due to EPS.

Tricyclics are cyclic chemical compounds that contain three fused rings of atoms.

Olanzapine/fluoxetine is a fixed-dose combination medication containing olanzapine (Zyprexa), an atypical antipsychotic, and fluoxetine (Prozac), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Olanzapine/fluoxetine is primarily used to treat the depressive episodes of bipolar I disorder as well as treatment-resistant depression.

Sultopride (trade names Barnetil, Barnotil, Topral) is an atypical antipsychotic of the benzamide chemical class used in Europe, Japan, and Hong Kong for the treatment of schizophrenia. It was launched by Sanofi-Aventis in 1976. Sultopride acts as a selective D2 and D3 receptor antagonist. It has also been shown to have clinically relevant affinity for the GHB receptor as well, a property it shares in common with amisulpride and sulpiride.

Blonanserin, sold under the brand name Lonasen, is a relatively new atypical antipsychotic commercialized by Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma in Japan and Korea for the treatment of schizophrenia. Relative to many other antipsychotics, blonanserin has an improved tolerability profile, lacking side effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms, excessive sedation, or hypotension. As with many second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics it is significantly more efficacious in the treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia compared to first-generation (typical) antipsychotics such as haloperidol.

NMDA receptor modulators are a new form of antipsychotic that are in Phase II FDA studies. The first compound studied was glycine which was hypothesized by Daniel Javitt after observation that people with phencyclidine(PCP)-induced psychosis were lacking in glutamate transmission. In giving glycine to people with PCP-induced psychosis a recovery rate was noted. From there, it was hypothesized that people with psychosis from schizophrenia would benefit from increased glutamate transmission and glycine was added with strong recovery rates noted especially in the area of negative and cognitive symptoms. Glycine, however, sporadic results aside remains an adjunct antipsychotic and an unworkable compound. However, the Eli Lilly and Company study drug LY-2140023 is being studied as a primary antipsychotic and is showing strong recovery rates, especially in the area of negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. Tardive dyskinesia, diabetes and other standard complications have not been noted:

Treatment with LY2140023, like treatment with olanzapine, was safe and well-tolerated; treated patients showed statistically significant improvements in both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia compared to placebo. Notably, patients treated with LY-2140023 did not differ from placebo-treated patients with respect to prolactin elevation, extrapyramidal symptoms or weight gain. These data suggest that mGlu2/3 receptor agonists have antipsychotic properties and may provide a new alternative for the treatment of schizophrenia.

Pomaglumetad (LY-404,039) is an amino acid analog drug that acts as a highly selective agonist for the metabotropic glutamate receptor group II subtypes mGluR2 and mGluR3. Pharmacological research has focused on its potential antipsychotic and anxiolytic effects. Pomaglumetad is intended as a treatment for schizophrenia and other psychotic and anxiety disorders by modulating glutamatergic activity and reducing presynaptic release of glutamate at synapses in limbic and forebrain areas relevant to these disorders. Human studies investigating therapeutic use of pomaglumetad have focused on the prodrug LY-2140023, a methionine amide of pomaglumetad (also called pomaglumetad methionil) since pomaglumetad exhibits low oral absorption and bioavailability in humans.

Umespirone (KC-9172) is a drug of the azapirone class which possesses anxiolytic and antipsychotic properties. It behaves as a 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist (Ki = 15 nM), D2 receptor partial agonist (Ki = 23 nM), and α1-adrenoceptor receptor antagonist (Ki = 14 nM), and also has weak affinity for the sigma receptor (Ki = 558 nM). Unlike many other anxiolytics and antipsychotics, umespirone produces minimal sedation, cognitive/memory impairment, catalepsy, and extrapyramidal symptoms.

Antipsychotic switching refers to the process of switching out one antipsychotic for another antipsychotic. There are multiple indications for switching antipsychotics, including inadequate efficacy and drug intolerance. There are several strategies that have been theorized for antipsychotic switching, based upon the timing of discontinuation and tapering of the original antipsychotic and the timing of initiation and titration of the new antipsychotic. Major adverse effects from antipsychotic switching may include supersensitivity syndromes, withdrawal, and rebound syndromes.

Bromerguride (INN), also known as 2-bromolisuride, is an antidopaminergic and serotonergic agent of the ergoline group which was described as having atypical antipsychotic properties but was never marketed. It was the first antidopaminergic ergoline derivative to be discovered. The pharmacodynamic actions of bromerguride are said to be "reversed" relative to its parent compound lisuride, a dopaminergic agent.