The Rök runestone is one of the most famous runestones, featuring the longest known runic inscription in stone. It can now be seen beside the church in Rök, Ödeshög Municipality, Östergötland, Sweden. It is considered the first piece of written Swedish literature and thus it marks the beginning of the history of Swedish literature.

A rune is a letter in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write Germanic languages before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised purposes thereafter. In addition to representing a sound value, runes can be used to represent the concepts after which they are named (ideographs). Scholars refer to instances of the latter as Begriffsrunen. The Scandinavian variants are also known as fuþark, or futhark, these names derived from the first six letters of the script, ⟨ᚠ⟩, ⟨ᚢ⟩, ⟨ᚦ⟩, ⟨ᚨ⟩/⟨ᚬ⟩, ⟨ᚱ⟩, and ⟨ᚲ⟩/⟨ᚴ⟩, corresponding to the Latin letters ⟨f⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨þ⟩/⟨th⟩, ⟨a⟩, ⟨r⟩, and ⟨k⟩. The Anglo-Saxon variant is futhorc, or fuþorc, due to changes in Old English of the sounds represented by the fourth letter, ⟨ᚨ⟩/⟨ᚩ⟩.

The Younger Futhark, also called Scandinavian runes, is a runic alphabet and a reduced form of the Elder Futhark, with only 16 characters, in use from about the 9th century, after a "transitional period" during the 7th and 8th centuries. The reduction, somewhat paradoxically, happened at the same time as phonetic changes that led to a greater number of different phonemes in the spoken language, when Proto-Norse evolved into Old Norse. Also, the writing custom avoided carving the same rune consecutively for the same sound, so the spoken distinction between long and short vowels was lost in writing. Thus, the language included distinct sounds and minimal pairs that were written the same.

The Elder Futhark, also known as the Older Futhark, Old Futhark, or Germanic Futhark, is the oldest form of the runic alphabets. It was a writing system used by Germanic peoples for Northwest Germanic dialects in the Migration Period. Inscriptions are found on artifacts including jewelry, amulets, plateware, tools, and weapons, as well as runestones in Scandinavia, from the 2nd to the 10th centuries.

The Kylver stone, listed in the Rundata catalog as runic inscription G 88, is a Swedish runestone which dates from about 400 AD. It is notable for its listing of each of the runes in the Elder Futhark.

Proto-Norse was an Indo-European language spoken in Scandinavia that is thought to have evolved as a northern dialect of Proto-Germanic in the first centuries CE. It is the earliest stage of a characteristically North Germanic language, and the language attested in the oldest Scandinavian Elder Futhark inscriptions, spoken from around the 2nd to the 8th centuries CE. It evolved into the dialects of Old Norse at the beginning of the Viking Age around 800 CE, which later themselves evolved into the modern North Germanic languages.

A runic inscription is an inscription made in one of the various runic alphabets. They generally contained practical information or memorials instead of magic or mythic stories. The body of runic inscriptions falls into the three categories of Elder Futhark, Anglo-Frisian Futhorc and Younger Futhark.

Seeland-II-C is a Scandinavian bracteate from Zealand, Denmark, that has been dated to the Migration period. The bracteate bears an Elder Futhark inscription which reads as:

Erilaz or Erilaʀ is a Migration period Proto-Norse word attested on various Elder Futhark inscriptions, which has often been interpreted to mean "magician" or "rune master", viz. one who is capable of writing runes to magical effect. However, as Mees (2003) has shown, the word is an ablaut variant of earl, and is also thought to be linguistically related to the name of the tribe of the Heruli, so it is probably merely an old Germanic military title.

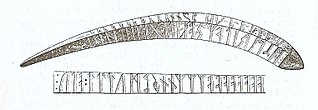

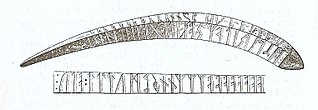

The Lindholm "amulet", listed as DR 261 in Rundata, is a bone piece, carved into the shape of a rib, dated to the 2nd to 4th centuries and has a runic inscription. The Lindholm bone piece is dated between 375CE to 570CE and it is around 17 centimeters long at its longest points. It currently resides at Lund University Historical Museum in Sweden.

A bind rune or bindrune is a Migration Period Germanic ligature of two or more runes. They are extremely rare in Viking Age inscriptions, but are common in earlier (Proto-Norse) and later (medieval) inscriptions.

The Tjurkö Bracteates, listed by Rundata as DR BR75 and DR BR76, are two bracteates found on Tjurkö, Eastern Hundred, Blekinge, Sweden, bearing Elder Futhark runic inscriptions in Proto-Norse.

There is some evidence that, in addition to being a writing system, runes historically served purposes of magic. This is the case from the earliest epigraphic evidence of the Roman to the Germanic Iron Age, with non-linguistic inscriptions and the alu word. An erilaz appears to have been a person versed in runes, including their magic applications.

The Järsberg Runestone is a runestone in the elder futhark near Kristinehamn in Värmland, Sweden.

The Noleby Runestone, which is also known as the Fyrunga Runestone or Vg 63 for its Rundata catalog listing, is a runestone in Proto-Norse which is engraved with the Elder Futhark. It was discovered in 1894 at the farm of Stora Noleby in Västergötland, Sweden.

The Sønder Kirkeby Runestone, listed as runic inscription DR 220 in the Rundata catalog, is a Viking Age memorial runestone that was discovered in Sønder Kirkeby, which is located about 5 kilometers east of Nykøbing Falster, Denmark.

The swastika design is known from artefacts of various cultures since the Neolithic, and it recurs with some frequency on artefacts dated to the Germanic Iron Age, i.e. the Migration period to Viking Age period in Scandinavia, including the Vendel era in Sweden, attested from as early as the 3rd century in Elder Futhark inscriptions and as late as the 9th century on Viking Age image stones.

The Læborg or Laeborg Runestone, listed as DR 26 in the Rundata catalog, is a Viking Age memorial runestone located outside of the village hall or Forsamlinghus in Læborg, which is about 3 kilometers north of Vejen, Denmark. The stone includes two depictions of the hammer of the Norse pagan god Thor.

The Asferg Runestone, listed as DR 121 in the Rundata catalog, is a Viking Age memorial runestone found at Asferg, which is about 10 km northeast of Randers, Aarhus County, Region Midtjylland, Denmark.

The Strängnäs stone, or runic inscription Sö Fv2011;307, is a runestone inscribed with runes written in Proto-Norse using the Elder Futhark alphabet. It was discovered in 1962, when a stove was demolished in a house at Klostergatan 4, in Strängnäs, Sweden. The stone is of Jotnian sandstone and measures 21 centimetres (8.3 in) in length, 13 centimetres (5.1 in) in width and 7.5 centimetres (3.0 in) in thickness.