The Kingdom of Jerusalem, also known as the Crusader Kingdom, was one of the Crusader states established in the Levant immediately after the First Crusade. It lasted for almost two hundred years, from the accession of Godfrey of Bouillon in 1099 until the fall of Acre in 1291. Its history is divided into two periods with a brief interruption in its existence, beginning with its collapse after the siege of Jerusalem in 1187 and its restoration after the Third Crusade in 1192.

The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem is the Latin Catholic ecclesiastical patriarchate in Jerusalem, officially seated in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It was originally established in 1099, with the Kingdom of Jerusalem encompassing the territories in the Holy Land newly conquered by the First Crusade. From 1374 to 1847 it was a titular see, with the patriarchs of Jerusalem being based at the Basilica di San Lorenzo fuori le Mura in Rome. Pope Pius IX re-established a resident Latin patriarch in 1847.

The Crusader states, or Outremer, were four Catholic polities that existed in the Levant from 1098 to 1291. Following the principles of feudalism, the foundation for these polities was laid by the First Crusade by the European Christians, which was proclaimed by the Latin Church in 1095 in order to reclaim the Holy Land after it was lost to the 7th-century Arab Muslim conquest. Situated on the Eastern Mediterranean, the four states were, in order from north to south: the County of Edessa (1098–1144), the Principality of Antioch (1098–1268), the County of Tripoli (1102–1289), and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291).

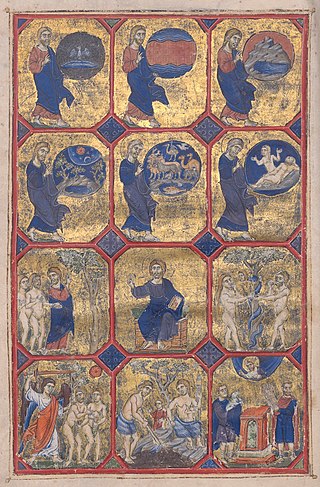

The medieval art of the Western world covers a vast scope of time and place, with over 1000 years of art in Europe, and at certain periods in Western Asia and Northern Africa. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional art, genres, revivals, the artists' crafts, and the artists themselves.

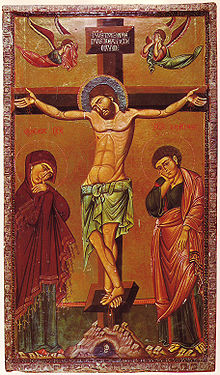

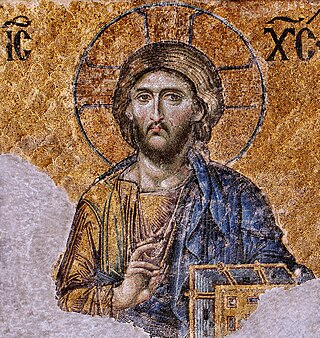

Byzantine art comprises the body of artistic products of the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of western Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward.

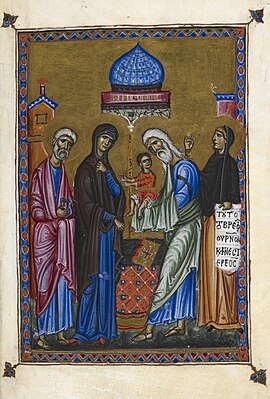

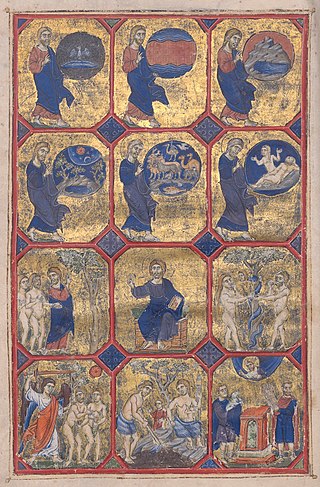

The Melisende Psalter is an illuminated manuscript commissioned around 1135 in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, probably by King Fulk for his wife Queen Melisende. It is a notable example of Crusader art, which resulted from a merging of the artistic styles of Roman Catholic Europe, the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine Empire and the art of the Armenian illuminated manuscript.

The king or queen of Jerusalem was the supreme ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a Crusader state founded in Jerusalem by the Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade, when the city was conquered in 1099. Most of them were men, but there were also five queens regnant of Jerusalem, either reigning alone suo jure, or as co-rulers of husbands who reigned as kings of Jerusalem jure uxoris.

The Cenacle, also known as the Upper Room, is a room in Mount Zion in Jerusalem, just outside the Old City walls, traditionally held to be the site of the Last Supper, the final meal that, in the Gospel accounts, Jesus held with the apostles.

The siege of Acre took place in 1291 and resulted in the Crusaders' losing control of Acre to the Mamluks. It is considered one of the most important battles of the period. Although the crusading movement continued for several more centuries, the capture of the city marked the end of further crusades to the Levant. When Acre fell, the Crusaders lost their last major stronghold of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. They still maintained a fortress at the northern city of Tartus, engaged in some coastal raids, and attempted an incursion from the tiny island of Ruad; but, when they lost that, too, in a siege in 1302, the Crusaders no longer controlled any part of the Holy Land.

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Christian Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these military expeditions are those to the Holy Land between 1095 and 1291 that had the objective of reconquering Jerusalem and its surrounding area from Muslim rule after the region had been conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate centuries earlier. Beginning with the First Crusade, which resulted in the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, dozens of military campaigns were organised, providing a focal point of European history for centuries. Crusading declined rapidly after the 15th century.

Jaroslav Thayer Folda III is a medievalist, in which field he is a Haskins Medal winner; he is a scholar in the history of the art of the Crusades and the N. Ferebee Taylor Professor of the History of Art at the University of North Carolina. His area of interest for teaching and research is the art of the Middle Ages in Europe and the Mediterranean world.

Burchard of Mount Sion, was a German priest, Dominican friar, pilgrim and author probably from Magdeburg in northern Germany, who travelled to the Middle East at the end of the 13th century. There he wrote his book called: Descriptio Terrae Sanctae or "Description of the Holy Land" which is considered to be of "extraordinary importance".

In ecclesiastical architecture, a ciborium is a canopy or covering supported by columns, freestanding in the sanctuary, that stands over and covers the altar in a church. It may also be known by the more general term of baldachin, though ciborium is often considered more correct for examples in churches. Really a baldachin should have a textile covering, or at least, as at Saint Peter’s in Rome, imitate one. There are exceptions; Bernini's structure in Saint Peter's, Rome is always called the baldachin.

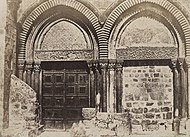

The Cathedral of Our Lady of Tortosa was a Catholic cathedral in the city of Tartus, Syria. Erected during the 12th century, it has been described by historians as "the best-preserved religious structure of the Crusades." The cathedral was popular among pilgrims during the Crusades because Saint Peter was said to have founded a small church there dedicated to the Virgin Mary. After it was captured by the Mamluks, the cathedral was turned into a mosque. Today, the building serves as the National Museum of Tartus.

The siege of Tyre took place from 12 November 1187 to 1 January 1188. An Ayyubid army commanded by Saladin made an amphibious assault on the city, defended by Conrad of Montferrat. After two months of continuous struggle, Saladin dismissed his army and retreated to Acre.

The History of Jerusalem during the Kingdom of Jerusalem began with the capture of the city by the Latin Christian forces at the apogee of the First Crusade. At that point it had been under Muslim rule for over 450 years. It became the capital of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, until it was again conquered by the Ayyubids under Saladin in 1187. For the next forty years, a series of Christian campaigns, including the Third and Fifth Crusades, attempted in vain to retake the city, until Emperor Frederick II led the Sixth Crusade and successfully negotiated its return in 1229.

Koz Castle, or Kürşat Castle is a castle in the Altınözü district of the Hatay Province of Turkey, built on a small hill where the Kuseyr Creek starts. It was built by the Principality of Antioch out of ashlar. The castle used to have a gate to the north, but this gate no longer exists and the eastern side of the castle has been leveled, with some original barns left. Some bastions of the castle stand to this day.

Abbey of Saint Mary of the Valley of Jehosaphat was a Benedictine abbey situated east of the Old City of Jerusalem, founded by Godfrey of Bouillon on the believed site of the Tomb of the Virgin Mary.

Thietmar or Dithmar was a German Christian pilgrim who visited the Holy Land in 1217–1218 and wrote an account of his travels, the Liber peregrinationis.

The Acre Bible is a partial Old French version of the Old Testament, containing both new and revised translations of 15 canonical and 4 deuterocanonical books, plus a prologue and glosses. The books are Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, Judith, Esther, Job, Tobit, Proverbs, 1 and 2 Maccabees and Ruth. It is an early and somewhat rough vernacular translation. Its version of Job is the earliest vernacular translation in Western Europe.