The Ascension of Jesus is the Christian belief, reflected in the major Christian creeds and confessional statements, that Jesus ascended to Heaven after his resurrection, where he was exalted as Lord and Christ, sitting at the right hand of God.

In art, a Madonna is a representation of Mary, either alone or with her child Jesus. These images are central icons for both the Catholic and Orthodox churches. The word is from Italian ma donna 'my lady' (archaic). The Madonna and Child type is very prevalent in Christian iconography, divided into many traditional subtypes especially in Eastern Orthodox iconography, often known after the location of a notable icon of the type, such as the Theotokos of Vladimir, Agiosoritissa, Blachernitissa, etc., or descriptive of the depicted posture, as in Hodegetria, Eleusa, etc.

Christian art is sacred art which uses subjects, themes, and imagery from Christianity. Most Christian groups use or have used art to some extent, including early Christian art and architecture and Christian media.

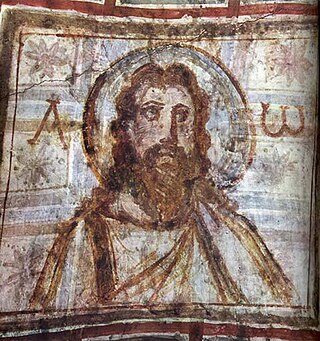

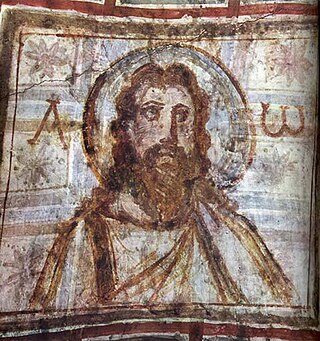

The depiction of Jesus in pictorial form dates back to early Christian art and architecture, as aniconism in Christianity was rejected within the ante-Nicene period. It took several centuries to reach a conventional standardized form for his physical appearance, which has subsequently remained largely stable since that time. Most images of Jesus have in common a number of traits which are now almost universally associated with Jesus, although variants are seen.

An aureola or aureole is the radiance of luminous cloud which, in paintings of sacred personages, surrounds the whole figure.

The Dormition of the Mother of God is a Great Feast of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Catholic Churches. It celebrates the "falling asleep" (death) of Mary the Theotokos, and her being taken up into heaven. The Feast of the Dormition is observed on August 15, which for the churches using the Julian calendar corresponds to August 28 on the Gregorian calendar. The Armenian Apostolic Church celebrates the Dormition not on a fixed date, but on the Sunday nearest 15 August. In Western Churches the corresponding feast is known as the Assumption of Mary, with the exception of the Scottish Episcopal Church, which has traditionally celebrated the Falling Asleep of the Blessed Virgin Mary on August 15.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the feast of the death and Resurrection of Jesus, called Pascha (Easter), is the greatest of all holy days and as such it is called the "feast of feasts". Immediately below it in importance, there is a group of Twelve Great Feasts. Together with Pascha, these are the most significant dates on the Orthodox liturgical calendar. Eight of the great feasts are in honor of Jesus Christ, while the other four are dedicated to the Virgin Mary—the Theotokos.

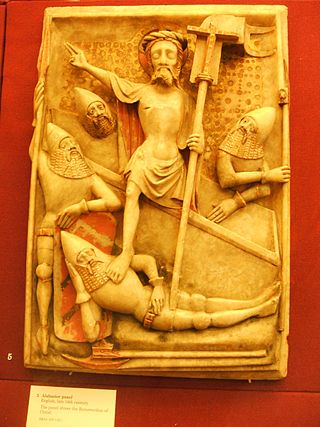

A doubting Thomas is a skeptic who refuses to believe without direct personal experience – a reference to the Gospel of John's depiction of the Apostle Thomas, who, in John's account, refused to believe the resurrected Jesus had appeared to the ten other apostles until he could see and feel Jesus's crucifixion wounds.

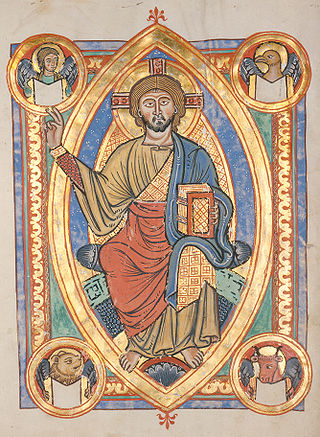

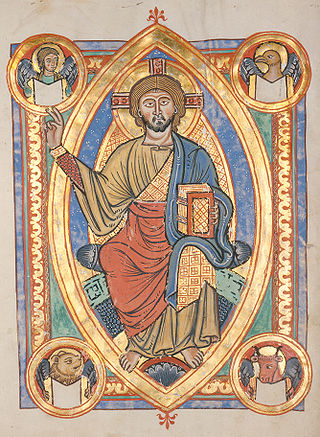

A mandorla is an almond-shaped aureola, i.e. a frame that surrounds the totality of an iconographic figure. It is usually synonymous with vesica, a lens shape. Mandorlas often surround the figures of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary in traditional Christian iconography. It is distinguished from a halo in that it encircles the entire body and not just the head. It is commonly used to frame the figure of Christ in Majesty in early medieval and Romanesque art, as well as Byzantine art of the same periods. It is the shape generally used for mediaeval ecclesiastical seals, secular seals generally being round.

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary does not appear in the New Testament, but appears in apocryphal literature of the 3rd and 4th centuries, and by 1000 was widely believed in the Western Church, though not made formal Catholic dogma until 1950. It first became a popular subject in Western Christian art in the 12th century, along with other narrative scenes from the Life of the Virgin, and the Coronation of the Virgin. These "Marian" subjects were especially promoted by the Cistercian Order and Saint Bernard of Clairvaux.

Poitiers Cathedral is a Roman Catholic church in Poitiers, France. It is the seat of the Archbishop of Poitiers.

Christ in Majesty or Christ in Glory is the Western Christian image of Christ seated on a throne as ruler of the world, always seen frontally in the centre of the composition, and often flanked by other sacred figures, whose membership changes over time and according to the context. The image develops from Early Christian art, as a depiction of the Heavenly throne as described in 1 Enoch, Daniel 7, and The Apocalypse of John. In the Byzantine world, the image developed slightly differently into the half-length Christ Pantocrator, "Christ, Ruler of All", a usually unaccompanied figure, and the Deesis, where a full-length enthroned Christ is entreated by Mary and St. John the Baptist, and often other figures. In the West, the evolving composition remains very consistent within each period until the Renaissance, and then remains important until the end of the Baroque, in which the image is ordinarily transported to the sky.

The Coronation of the Virgin or Coronation of Mary is a subject in Christian art, especially popular in Italy in the 13th to 15th centuries, but continuing in popularity until the 18th century and beyond. Christ, sometimes accompanied by God the Father and the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove, places a crown on the head of Mary as Queen of Heaven. In early versions the setting is a Heaven imagined as an earthly court, staffed by saints and angels; in later versions Heaven is more often seen as in the sky, with the figures seated on clouds. The subject is also notable as one where the whole Christian Trinity is often shown together, sometimes in unusual ways. Crowned Virgins are also seen in Eastern Orthodox Christian icons, specifically in the Russian Orthodox church after the 18th century. Mary is sometimes shown, in both Eastern and Western Christian art, being crowned by one or two angels, but this is considered a different subject.

The Seven Joys of the Virgin is a popular devotion to events of the life of the Virgin Mary, arising from a trope of medieval devotional literature and art.

Mary has been one of the major subjects of Western art for centuries. There is an enormous quantity of Marian art in the Catholic Church, covering both devotional subjects such as the Virgin and Child and a range of narrative subjects from the Life of the Virgin, often arranged in cycles. Most medieval painters, and from the Reformation to about 1800 most from Catholic countries, have produced works, including old masters such as Michelangelo and Botticelli.

The life of Christ as a narrative cycle in Christian art comprises a number of different subjects showing events from the life of Jesus on Earth. They are distinguished from the many other subjects in art showing the eternal life of Christ, such as Christ in Majesty, and also many types of portrait or devotional subjects without a narrative element.

The depiction of the Virgin Mary as the Queen of Heaven has been a popular subject in Catholic art for centuries.

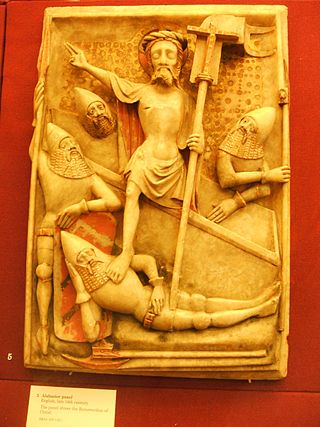

The resurrection of Jesus has long been central to Christian faith and Christian art, whether as a single scene or as part of a cycle of the Life of Christ. In the teachings of the traditional Christian churches, the sacraments derive their saving power from the passion and resurrection of Christ, upon which the salvation of the world entirely depends. The redemptive value of the resurrection has been expressed through Christian art, as well as being expressed in theological writings.

The Transfiguration of Jesus has been an important subject in Christian art, above all in the Eastern church, some of whose most striking icons show the scene.

The iconostasis of the Cathedral of Hajdúdorog is the largest Greek Catholic icon screen in Hungary. It is 11 m tall and 7 m wide, holding 54 icons on five tiers. Creating such a monumental work of art requires a number of different craftsmen. Miklós Jankovits was hired by the Greek Catholic parish of Hajdúdorog in 1799 to carve the wooden framework, including the doors and the icon frames of the iconostasis. Mátyás Hittner and János Szűts could only start the painting and gilding works in 1808. The last icon was completed in 1816.