A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input. An individual's construction of reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behavior in the world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, and irrationality.

Attention is the concentration of awareness on some phenomenon to the exclusion of other stimuli. It is a process of selectively concentrating on a discrete aspect of information, whether considered subjective or objective. William James (1890) wrote that "Attention is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration, of consciousness are of its essence." Attention has also been described as the allocation of limited cognitive processing resources. Attention is manifested by an attentional bottleneck, in terms of the amount of data the brain can process each second; for example, in human vision, only less than 1% of the visual input data can enter the bottleneck, leading to inattentional blindness.

Metacognition is an awareness of one's thought processes and an understanding of the patterns behind them. The term comes from the root word meta, meaning "beyond", or "on top of". Metacognition can take many forms, such as reflecting on one's ways of thinking and knowing when and how to use particular strategies for problem-solving. There are generally two components of metacognition: (1) knowledge about cognition and (2) regulation of cognition. A metacognitive model differs from other scientific models in that the creator of the model is per definition also enclosed within it. Scientific models are often prone to distancing the observer from the object or field of study whereas a metacognitive model in general tries to include the observer in the model.

Depressive realism is the hypothesis developed by Lauren Alloy and Lyn Yvonne Abramson that depressed individuals make more realistic inferences than non-depressed individuals. Although depressed individuals are thought to have a negative cognitive bias that results in recurrent, negative automatic thoughts, maladaptive behaviors, and dysfunctional world beliefs, depressive realism argues not only that this negativity may reflect a more accurate appraisal of the world but also that non-depressed individuals' appraisals are positively biased.

Affective neuroscience is the study of how the brain processes emotions. This field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The basis of emotions and what emotions are remains an issue of debate within the field of affective neuroscience.

Salience is that property by which some thing stands out. Salient events are an attentional mechanism by which organisms learn and survive; those organisms can focus their limited perceptual and cognitive resources on the pertinent subset of the sensory data available to them.

The dot-probe paradigm is a test used by cognitive psychologists to assess selective attention.

Attentional bias refers to how a person's perception is affected by selective factors in their attention. Attentional biases may explain an individual's failure to consider alternative possibilities when occupied with an existing train of thought. For example, cigarette smokers have been shown to possess an attentional bias for smoking-related cues around them, due to their brain's altered reward sensitivity. Attentional bias has also been associated with clinically relevant symptoms such as anxiety and depression.

Test anxiety is a combination of physiological over-arousal, tension and somatic symptoms, along with worry, dread, fear of failure, and catastrophizing, that occur before or during test situations. It is a psychological condition in which people experience extreme stress, anxiety, and discomfort during and/or before taking a test. This anxiety creates significant barriers to learning and performance. Research suggests that high levels of emotional distress have a direct correlation to reduced academic performance and higher overall student drop-out rates. Test anxiety can have broader consequences, negatively affecting a student's social, emotional and behavioural development, as well as their feelings about themselves and school.

Alcohol myopia is a cognitive-physiological theory on alcohol use disorder in which many of alcohol's social and stress-reducing effects, which may underlie its addictive capacity, are explained as a consequence of alcohol's narrowing of perceptual and cognitive functioning. The alcohol myopia model posits that rather than disinhibit, alcohol produces a myopia effect that causes users to pay more attention to salient environmental cues and less attention to less salient cues. Therefore, alcohol's myopic effects cause intoxicated people to respond almost exclusively to their immediate environment. This "nearsightedness" limits their ability to consider future consequences of their actions as well as regulate their reactive impulses.

Social anxiety is the anxiety and fear specifically linked to being in social settings. Some categories of disorders associated with social anxiety include anxiety disorders, mood disorders, autism spectrum disorders, eating disorders, and substance use disorders. Individuals with higher levels of social anxiety often avert their gazes, show fewer facial expressions, and show difficulty with initiating and maintaining a conversation. Social anxiety commonly manifests itself in the teenage years and can be persistent throughout life; however, people who experience problems in their daily functioning for an extended period of time can develop social anxiety disorder. Trait social anxiety, the stable tendency to experience this anxiety, can be distinguished from state anxiety, the momentary response to a particular social stimulus. Half of the individuals with any social fears meet the criteria for social anxiety disorder. Age, culture, and gender impact the severity of this disorder. The function of social anxiety is to increase arousal and attention to social interactions, inhibit unwanted social behavior, and motivate preparation for future social situations.

Rumination is the focused attention on the symptoms of one's mental distress, and on its possible causes and consequences, as opposed to its solutions, according to the Response Styles Theory proposed by Nolen-Hoeksema in 1998.

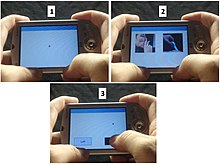

Cognitive bias modification (CBM) refers to procedures used in psychology that aim to directly change biases in cognitive processes, such as biased attention toward threat stimuli and biased interpretation of ambiguous stimuli as threatening. The procedures are designed to modify information processing via cognitive tasks that use basic learning principles and repeated practice to encourage a healthier thinking style in line with the training contingency.

Attentional control, colloquially referred to as concentration, refers to an individual's capacity to choose what they pay attention to and what they ignore. It is also known as endogenous attention or executive attention. In lay terms, attentional control can be described as an individual's ability to concentrate. Primarily mediated by the frontal areas of the brain including the anterior cingulate cortex, attentional control is thought to be closely related to other executive functions such as working memory.

Richard McNally is an American psychologist and director of clinical training at Harvard University's department of psychology. As a clinical psychologist and experimental psycho-pathologist, McNally studies anxiety disorders and related syndromes, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and complicated grief.

A cognitive vulnerability in cognitive psychology is an erroneous belief, cognitive bias, or pattern of thought that predisposes an individual to psychological problems. The vulnerability exists before the symptoms of a psychological disorder appear. After the individual encounters a stressful experience, the cognitive vulnerability shapes a maladaptive response that increases the likelihood of a psychological disorder.

Emotion perception refers to the capacities and abilities of recognizing and identifying emotions in others, in addition to biological and physiological processes involved. Emotions are typically viewed as having three components: subjective experience, physical changes, and cognitive appraisal; emotion perception is the ability to make accurate decisions about another's subjective experience by interpreting their physical changes through sensory systems responsible for converting these observed changes into mental representations. The ability to perceive emotion is believed to be both innate and subject to environmental influence and is also a critical component in social interactions. How emotion is experienced and interpreted depends on how it is perceived. Likewise, how emotion is perceived is dependent on past experiences and interpretations. Emotion can be accurately perceived in humans. Emotions can be perceived visually, audibly, through smell and also through bodily sensations and this process is believed to be different from the perception of non-emotional material.

Cognitive behavioral training (CBTraining), sometimes referred to as structured cognitive behavioral training, (SCBT) is an organized process that uses systematic, highly-structured tasks designed to improve cognitive functions. Functions such as working memory, decision making, and attention are thought to inform whether a person defaults to an impulsive behavior or a premeditated behavior. The aim of CBTraining is to affect a person's decision-making process and cause them to choose the premeditated behavior over the impulsive behavior in their everyday life. Through scheduled trainings that may be up to a few hours long and may be weekly or daily over a specific set of time, the goal of CBTraining is to show that focusing on repetitive, increasingly difficult cognitive tasks can transfer those skills to other cognitive processes in your brain, leading to behavioral change. There has been a recent resurgence of interest in this field with the invention of new technologies and a greater understanding of cognition in general.

Interpretive bias or interpretation bias is an information-processing bias, the tendency to inappropriately analyze ambiguous stimuli, scenarios and events. One type of interpretive bias is hostile attribution bias, wherein individuals perceive benign or ambiguous behaviors as hostile. For example, a situation in which one friend walks past another without acknowledgement. The individual may interpret this behavior to mean that their friend is angry with them.

Affect labeling is an implicit emotional regulation strategy that can be simply described as "putting feelings into words". Specifically, it refers to the idea that explicitly labeling one's, typically negative, emotional state results in a reduction of the conscious experience, physiological response, and/or behavior resulting from that emotional state. For example, writing about a negative experience in one's journal may improve one's mood. Some other examples of affect labeling include discussing one's feelings with a therapist, complaining to friends about a negative experience, posting one's feelings on social media or acknowledging the scary aspects of a situation.