Bible translations into Serbian started to appear in fragments in the 11th century. Efforts to make a complete translation started in the 16th century. The first published complete translations were made in the 19th century.

Bible translations into Serbian started to appear in fragments in the 11th century. Efforts to make a complete translation started in the 16th century. The first published complete translations were made in the 19th century.

Among first translations in Serbian are the famous Codex Marianus (written in Glagolitic script) from 11th century, and Miroslav Gospel (written in Cyrillic script) from 12th century. [1] [2]

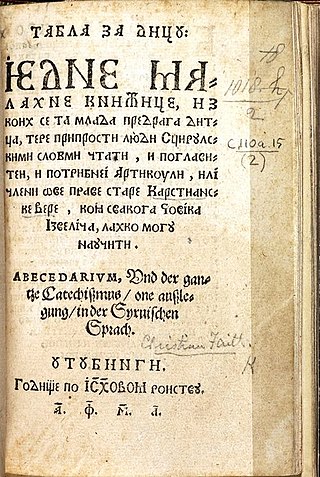

In 1561 South Slavic Bible Institute was established for publishing Protestant books translated to South Slavic languages. For this task, the president of this institute Primož Trubar engaged Stjepan Konzul Istranin and Antun Dalmatin as translators for Serbian. [3] The Cyrillic text was the responsibility of Antun Dalmatin. [4] The type for printing the Cyrillic-script texts was cast by craftsmen from Nuremberg. [5] The first attempt to use it failed, and the type had to be reconstructed. [6] In 1561 in Tübingen three small books were printed (including Abecedarium and Catechismus ) in the Glagolitic script. [7] The same books were also printed in Ulach in Serbian with the reconstructed Cyrillic type. [6] [7] For a considerable amount of time, the institute tried to employ a certain Dimitrije Serb to help Istranin and Dalmatin, but without success. [8] Eventually, they managed to employ two Serbian Orthodox priests - Jovan Maleševac from Ottoman Bosnia and Matija Popović from Ottoman Serbia. [8]

At the beginning of the 18th century, Gavrilo Stefanović Venclović translated some 20,000 pages of old biblical literature into vernacular Serbian. [9]

The first Serbian gospel was printed in 1537 in the Rujno Monastery printing house, and in Belgrade printing house in 1552, and also in Mrkšina crkva printing house in 1562. Despite the retained archaic forms and vocabulary, these texts were understandable to the people. Meanwhile, the first modern printed Bible was of Atanasije Stojković (published by the Russian Bible Society at Saint Petersburg, 1824) but was not written in the vernacular Serbian, but was a mixture of Church Slavonic and Serbian. Stojković later translated the New Testament to Serbian in 1830. A more popular translation of the New Testament by Vuk Karadžić was published in Vienna in 1847, and was combined with the translation of the Old Testament of 1867 by Đuro Daničić in Belgrade, printed together in 1868. [10]

Other subsequent translations are the following:

| Translation by | Genesis 1:1 – 3 | John 3:16 |

|---|---|---|

| Đuro Daničić, linguist (Old Testament in 1867), and Vuk Karadžić, linguist (New Testament in 1847) | У почетку створи Бог небо и земљу. А земља беше без обличја и пуста, и беше тама над безданом; и дух Божји дизаше се над водом. И рече Бог: Нека буде светлост. И би светлост. | Јер Богу тако омиље свијет да је и сина својега јединороднога дао, да ни један који га вјерује не погине, него да има живот вјечни. |

| Lujo Bakotić, lexicographer (in 1933) | У почетку створи Бог небо и земљу. Земља беше пуста и празна; над безданом беше тама, и дух Божји лебдијаше над водама. Бог рече: Нека буде светлост. И би светлост. | Јер Бог толико љуби свет, да је и Сина свога јединорођенога дао, да ни један који у њега верује не пропадне, него да има живот вечни. [11] |

| Dimitrije Stefanović, Serbian Orthodox priest (in 1934) | New Testament only | Јер је Бог тако заволео свет, да је и Сина свога јединорођенога дао, да ниједан који верује у њега, не погине, него да има живот вечни. |

| Emilijan Čarnić , Serbian Orthodox theologian (in 1973) | New Testament only | Јер Бог је тако заволео свет да је свог јединородног Сина дао, да сваки - ко верује у њега - не пропадне, него да има вечни живот. |

| Serbian Orthodox Synod (in 1984) | New Testament only | Јер Бог тако завоље свијет да је Сина својега Јединороднога дао, да сваки који вјерује у њега не погине, него да има живот вјечни. |

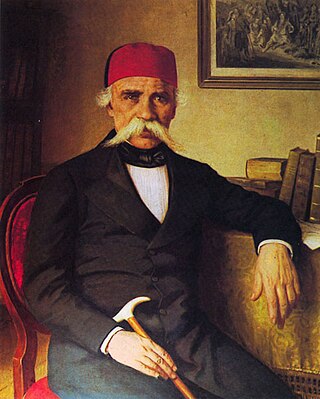

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić was a Serbian philologist, anthropologist and linguist. He was one of the most important reformers of the modern Serbian language. For his collection and preservation of Serbian folktales, Encyclopædia Britannica labelled Karadžić "the father of Serbian folk-literature scholarship." He was also the author of the first Serbian dictionary in the new reformed language. In addition, he translated the New Testament into the reformed form of the Serbian spelling and language.

Đuro Daničić, born Đorđe Popović and also known as Đura Daničić, was a Serbian philologist, translator, linguistic historian and lexicographer. He was a prolific scholar at the Belgrade Lyceum.

The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet is a variation of the Cyrillic script used to write the Serbian language, updated in 1818 by the Serbian philologist and linguist Vuk Karadžić. It is one of the two alphabets used to write modern standard Serbian, the other being Gaj's Latin alphabet.

The Vienna Literary Agreement was the result of a meeting held in March 1850, when writers from Croatia, Serbia and Carniola (Slovenia) met to discuss the extent to which their literatures could be conjoined and united to create a standardized Serbo-Croatian language.

The agreement recognized the commonality of South Slavic dialects and enumerated a basic set of grammar rules which they shared.

Đuro is a South Slavic male given name derived from Đurađ.

Bible translations into Croatian started to appear in fragments in the 14th century. Efforts to make a complete translation started in the 16th century. The first published complete translations were made in the 19th century.

Jovan Maleševac was a Serbian Orthodox monk and scribe who collaborated in 1561 with the Slovene Protestant reformer Primož Trubar to print religious books in Cyrillic. Between 1524 and 1546, Maleševac wrote five liturgical books in Church Slavonic at Serbian Orthodox monasteries in Herzegovina and Montenegro. He later settled in the region of White Carniola, in present-day Slovenia. In 1561, he was engaged by Trubar to proof-read Cyrillic Protestant liturgical books produced in the South Slavic Bible Institute in Urach, Germany, where he stayed for five months.

Stipan/Stjepan Konzul Istranin, or Stephanus Consul, was a 16th-century Croatian Protestant reformator who authored and translated religious books to Čakavian dialect. Istranin was the most important Croatian Protestant writer.

The South Slavic Bible Institute was established in Urach in January 1561 by Baron Hans von Ungnad, who was its owner and patron. Ungnad was supported by Christoph, Duke of Württemberg, who allowed Ungnad to use his castle of Amandenhof near Urach as a seat of this institute.

Antun Aleksandrović Dalmatin was 16th century Croatian translator and publisher of Protestant liturgical books.

Hans von Ungnad (1493–1564) was 16th-century Habsburg nobleman who was best known as founder of the South Slavic Bible Institute established to publish Protestant books translated to South Slavic languages.

Matija Popović was 16th-century Serbian Orthodox priest from Ottoman Bosnia. Popović was printer in the South Slavic Bible Institute.

Atanasije Stojković was a Serbian, Austrian and Russian writer, pedagogue, scholar, physicist, mathematician and astronomer. He is considered the founder of Russian meteoritics. Stojković was the president of the Imperial University of Kharkov from 1807 to 1809 and from 1811 to 1813.

Danilo Medaković was a Serbian writer, journalist and publisher. One of Serbia's leading publicists, Medaković had his own printing press in Novi Sad where he published several periodicals, magazines, and three newspapers, both political and literary. Milorad Medaković, also a writer and publisher, was his younger brother.

Juraj Juričić, was a Croatian Protestant preacher and translator. Born in Croatia, Juričić translated and wrote in German, Slovenian and Croatian. In his Slovenian translations there are many elements of Croatian.

Dimitrije Frušić, also known in Trieste as Demetrio Frussich was a prominent Serbian medical doctor, journalist, and publisher. He was the founder of the influential Novine Serbske together with Dimitrije Davidović in Vienna during the Serbian Enlightenment. He was a well-respected physician in his day who played an important role in the construction of a new hospital -- Ospedale Maggiore -- in Trieste.

Inok Sava, was a Serbian monk, scribe and traveller who published a Serbian Primer (syllabary) in 1597. Of rare books designated by the National Library of Serbia, Inok Sava's Prvi srpski bukvar is considered among the rarest.

Đorđe Trifunović is a Serbian literary scholar and literary historian of the University of Belgrade.

The Gospel of Saint Nicholas is a Serbian illuminated manuscript written on parchment in 13th from the Monastery of St. Nicholas of Rošci, with size of 16x10.5 cm, 144 pages and 17 editions of text on each of the pages decorated with illuminations, initials and flags, gold and silver details. According to the historian Pavel Šafarik (1858), this Gospel he calls it "The Gospel of Queen Jelena", was written for Helen of Anjou, between 1240 and 1250.

Jovan Bošković was a Serbian professor, philologist, librarian, and politician.