Bivalvia, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bivalves have no head and they lack some usual molluscan organs, like the radula and the odontophore. The class includes the clams, oysters, cockles, mussels, scallops, and numerous other families that live in saltwater, as well as a number of families that live in freshwater. The majority are filter feeders. The gills have evolved into ctenidia, specialised organs for feeding and breathing. Most bivalves bury themselves in sediment, where they are relatively safe from predation. Others lie on the sea floor or attach themselves to rocks or other hard surfaces. Some bivalves, such as the scallops and file shells, can swim. Shipworms bore into wood, clay, or stone and live inside these substances.

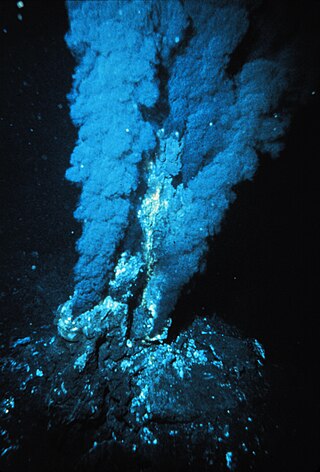

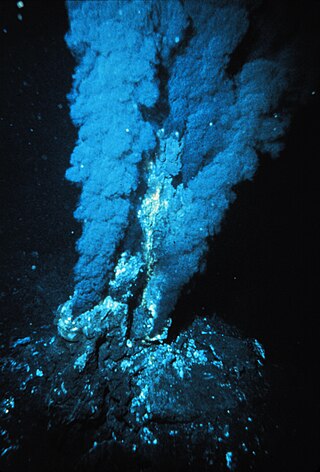

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspots. The dispersal of hydrothermal fluids throughout the global ocean at active vent sites creates hydrothermal plumes. Hydrothermal deposits are rocks and mineral ore deposits formed by the action of hydrothermal vents.

A cold seep is an area of the ocean floor where seepage of fluids rich in hydrogen sulfide, methane, and other hydrocarbons occurs, often in the form of a brine pool. Cold does not mean that the temperature of the seepage is lower than that of the surrounding sea water; on the contrary, its temperature is often slightly higher. The "cold" is relative to the very warm conditions of a hydrothermal vent. Cold seeps constitute a biome supporting several endemic species.

The Alvinellidae are a family of small, deep-sea polychaete worms endemic to hydrothermal vents in the Pacific Ocean. Belonging to the order Terebellida, the family contains two genera, Alvinella and Paralvinella; the former genus contains two valid species and the latter eight. Members of the family are termed alvinellids.

Riftia pachyptila, commonly known as the giant tube worm and less commonly known as the giant beardworm, is a marine invertebrate in the phylum Annelida related to tube worms commonly found in the intertidal and pelagic zones. R. pachyptila lives on the floor of the Pacific Ocean near hydrothermal vents. The vents provide a natural ambient temperature in their environment ranging from 2 to 30 °C, and this organism can tolerate extremely high hydrogen sulfide levels. These worms can reach a length of 3 m, and their tubular bodies have a diameter of 4 cm (1.6 in).

A veliger is the planktonic larva of many kinds of sea snails and freshwater snails, as well as most bivalve molluscs (clams) and tusk shells.

Alvinocarididae is a family of shrimp, originally described by M. L. Christoffersen in 1986 from samples collected by DSV Alvin, from which they derive their name. Shrimp of the family Alvinocarididae generally inhabit deep sea hydrothermal vent regions, and hydrocarbon cold seep environments. Carotenoid pigment has been found in their bodies. The family Alvinocarididae comprises 7 extant genera.

Chrysomallon squamiferum, commonly known as the scaly-foot gastropod, scaly-foot snail, sea pangolin, or volcano snail is a species of deep-sea hydrothermal-vent snail, a marine gastropod mollusc in the family Peltospiridae. This vent-endemic gastropod is known only from deep-sea hydrothermal vents in the Indian Ocean, where it has been found at depths of about 2,400–2,900 m (1.5–1.8 mi). C. squamiferum differs greatly from other deep-sea gastropods, even the closely related neomphalines. In 2019, it was declared endangered on the IUCN Red List, the first species to be listed as such due to risks from deep-sea mining of its vent habitat.

Colleen Marie Cavanaugh is an American academic microbiologist best known for her studies of hydrothermal vent ecosystems. As of 2002, she is the Edward C. Jeffrey Professor of Biology in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University and is affiliated with the Marine Biological Laboratory and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Cavanaugh was the first to propose that the deep-sea giant tube worm, Riftia pachyptila, obtains its food from bacteria living within its cells, an insight which she had as a graduate student at Harvard. Significantly, she made the connection that these chemoautotrophic bacteria were able to play this role through their use of chemosynthesis, the biological oxidation of inorganic compounds to synthesize organic matter from very simple carbon-containing molecules, thus allowing organisms such as the bacteria to exist in deep ocean without sunlight.

Ifremeria nautilei is a species of large, deepwater hydrothermal vent sea snail, a marine gastropod mollusk in the family Provannidae, and the only species in the genus Ifremeria. This species lives in the South Pacific Ocean

Thalassonerita is a monotypic genus of sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Neritidae. Its sole species is Thalassonerita naticoidea. T. naticoidea is endemic to underwater cold seeps in the northern Gulf of Mexico and in the Caribbean. Originally classified as Bathynerita, the genus was reassessed in 2019 after Thalassonerita was found to be a senior synonym of Bathynerita.

Bathymodiolus is a genus of deep-sea mussels, marine bivalve molluscs in the family Mytilidae. Many of them contain intracellular chemoautotrophic bacterial symbionts.

Bathymodiolus thermophilus is a species of large, deep water mussel, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family Mytilidae, the true mussels. The species was discovered at abyssal depths when submersible vehicles such as DSV Alvin began exploring the deep ocean. It occurs on the sea bed, often in great numbers, close to hydrothermal vents where hot, sulphur-rich water wells up through the floor of the Pacific Ocean.

Nuttallia obscurata, the purple mahogany clam, dark mahogany clam, varnish clam or savory clam, is a species of saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusk in the family Psammobiidae. It was first described to science by Lovell Augustus Reeve, a British conchologist, in 1857.

Thermarces cerberus is a species of ray-finned fish in the family Zoarcidae. This fish, commonly known as the pink vent fish, is associated with hydrothermal vents and cold seeps at bathypelagic depths in the East Pacific.

Vulcanolepas osheai, commonly referred to as O'Shea's vent barnacle, is a stalked barnacle of the family Neolepadidae. This species is endemic to New Zealand.

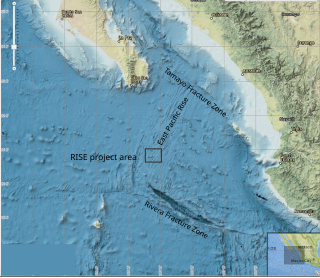

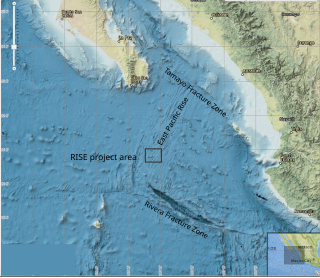

Kathleen (Kathy) Crane is an American marine geologist, best known for her contributions to the discovery of hydrothermal vents on the Galápagos Rift along the East Pacific Rise in the mid-1970s.

The hydrothermal vent microbial community includes all unicellular organisms that live and reproduce in a chemically distinct area around hydrothermal vents. These include organisms in the microbial mat, free floating cells, or bacteria in an endosymbiotic relationship with animals. Chemolithoautotrophic bacteria derive nutrients and energy from the geological activity at Hydrothermal vents to fix carbon into organic forms. Viruses are also a part of the hydrothermal vent microbial community and their influence on the microbial ecology in these ecosystems is a burgeoning field of research.

The RISE Project (Rivera Submersible Experiments) was a 1979 international marine research project which mapped and investigated seafloor spreading in the Pacific Ocean, at the crest of the East Pacific Rise (EPR) at 21° north latitude. Using a deep sea submersible (ALVIN) to search for hydrothermal activity at depths around 2600 meters, the project discovered a series of vents emitting dark mineral particles at extremely high temperatures which gave rise to the popular name, "black smokers". Biologic communities found at 21° N vents, based on chemosynthesis and similar to those found at the Galapagos spreading center, established that these communities are not unique. Discovery of a deep-sea ecosystem not based on sunlight spurred theories of the origin of life on Earth.

Rimicaris exoculata, commonly known as the 'blind shrimp', is a species of shrimp. It thrives on active hydrothermal edifices at deep-sea vents of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This species belongs to the Alvinocarididae family of shrimp, named after DSV Alvin, the vessel that collected the original samples described by M. L. Christoffersen in 1986. The name Rimicaris is derived from the Latin word 'rima', which means rift or fissure, in reference to the Mid Atlantic Ridge, and the Greek word 'karis', meaning shrimp. The species epithet 'exoculata' is derived from the Latin term 'exoculo', meaning deprived of eyes, referring to the highly modified, non-image-forming eyes.