The 2005 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was destructive and deadly to southern India, despite the weak storms. The basin covers the Indian Ocean north of the equator as well as inland areas, sub-divided by the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. Although the season began early with two systems in January, the bulk of activity was confined from September to December. The official India Meteorological Department tracked 12 depressions in the basin, and the unofficial Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) monitored two additional storms. Three systems intensified into a cyclonic storm, which have sustained winds of at least 63 km/h (39 mph), at which point the IMD named them.

The 2006 North Indian Ocean cyclone season had no bounds, but cyclones tend to form between April and December, with peaks in May and November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean.

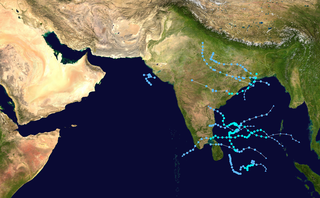

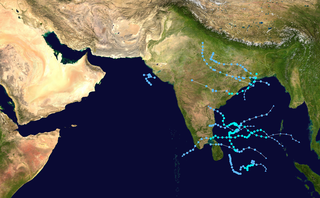

The 2000 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was fairly quiet compared to its predecessor, with all of the activity originating in the Bay of Bengal. The basin comprises the Indian Ocean north of the equator, with warnings issued by the India Meteorological Department (IMD) in New Delhi. There were six depressions throughout the year, of which five intensified into cyclonic storms – tropical cyclones with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) sustained over 3 minutes. Two of the storms strengthened into a Very Severe Cyclonic Storm, which has winds of at least 120 km/h (75 mph), equivalent to a minimal hurricane. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) also tracked storms in the basin on an unofficial basis, estimating winds sustained over 1 minute.

The 1996 North Indian Ocean cyclone season featured several deadly tropical cyclones, with over 2,000 people killed during the year. The India Meteorological Department (IMD) – the Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the northern Indian Ocean as recognized by the World Meteorological Organization – issued warnings for nine tropical cyclones in the region. Storms were also tracked on an unofficial basis by the American-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center, which observed one additional storm. The basin is split between the Bay of Bengal off the east coast of India and the Arabian Sea off the west coast. During the year, the activity was affected by the monsoon season, with most storms forming in June or after October.

The 1990 North Indian Ocean cyclone season featured a below average total of twelve cyclonic disturbances and one of the most intense tropical cyclones in the basin on record. During the season the systems were primarily monitored by the India Meteorological Department, while other warning centres such as the United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center also monitored the area. During the season, there were at least 1,577 deaths, while the systems caused over US$693 million in damages. The most significant system was the 1990 Andhra Pradesh cyclone, which was the most intense, damaging, and the deadliest system of the season.

The 2008 North Indian Ocean cyclone season officially ran throughout the year during 2008, with the first depression forming on April 27. The timeline includes information that was not operationally released, meaning that information from post-storm reviews by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC), and the India Meteorological Department (IMD), such as information on a storm that was not operationally warned on. This timeline documents all the storm formations, strengthening, weakening, landfalls, extratropical transitions, as well as dissipation's during the 2008 North Indian Ocean cyclone season.

The 1994 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was a below-average year in which eight tropical cyclones affected seven countries bordering the North Indian Ocean. The India Meteorological Department tracks all tropical cyclones in the basin, north of the equator. The first system developed on March 21 in the Bay of Bengal, the first March storm in the basin since 1938. The second storm was the most powerful cyclone of the season, attaining maximum sustained winds of 215 km/h (135 mph) in the northern Bay of Bengal. Making landfall near the border of Bangladesh and Myanmar, the cyclone killed 350 people and left US$125 million in damage.

The 2013 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was an event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation, in which tropical cyclones formed in the North Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea. The season had no official bounds, but cyclones typically formed between May and December, with the peak from October to November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean.

The 2014 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was an event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation. The season included two very severe cyclonic storms, both in October, and one other named cyclonic storm, classified according to the tropical cyclone intensity scale of the India Meteorological Department. Cyclone Hudhud is estimated to have caused US$3.58 billion in damage across eastern India, and more than 120 deaths.

Severe Cyclonic Storm Helen was a relatively weak tropical cyclone that formed in the Bay of Bengal Region on 18 November 2013, from the remnants of Tropical Storm Podul. It was classified as Deep Depression BOB 06 by the IMD on 19 November. As it was moving on a very slow northwest direction on 20 November, it became Cyclonic Storm Helen as it brought light to heavy rainfall in eastern India. It then became a Severe Cyclonic Storm on the afternoon hours of 21 November.

Very Severe Cyclonic Storm Lehar was a tropical cyclone that primarily affected the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. Lehar was the second most intense tropical cyclone of the 2013 season, surpassed by Cyclone Phailin, as well as one of the two relatively strong cyclones that affected Southern India in November 2013, the other being Cyclone Helen.

Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Hudhud was a strong tropical cyclone that caused extensive damage and loss of life in eastern India and Nepal during October 2014. Hudhud originated from a low-pressure system that formed under the influence of an upper-air cyclonic circulation in the Andaman Sea on October 6. Hudhud intensified into a cyclonic storm on October 8 and as a Severe Cyclonic Storm on October 9. Hudhud underwent rapid deepening in the following days and was classified as a Very Severe Cyclonic Storm by the IMD. Shortly before landfall near Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, on October 12, Hudhud reached its peak strength with three-minute wind speeds of 185 km/h (115 mph) and a minimum central pressure of 960 mbar (28.35 inHg). The system then drifted northwards towards Uttar Pradesh and Nepal, causing widespread rains in both areas and heavy snowfall in the latter.

The 2016 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was an event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation. It was the deadliest season since 2010, killing more than 400 people. The season was an average one, seeing four named storms, with one further intensifying into a very severe cyclonic storm. The first named storm, Roanu, developed on 19 May while the season's last named storm, Vardah, dissipated on 18 December. The North Indian Ocean cyclone season has no official bounds, but cyclones tend to form between April and December, with the two peaks in May and November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean.

The 2018 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was one of the most active North Indian Ocean cyclone seasons since 1992, with the formation of fourteen depressions and seven cyclones. The North Indian Ocean cyclone season has no official bounds, but cyclones tend to form between April and December, with the two peaks in May and November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean.

The 2019 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was the most active North Indian Ocean cyclone season on record, in terms of cyclonic storms, however the 1992 season was more active according to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center. The season featured 12 depressions, 11 deep depressions, 8 cyclonic storms, 6 severe cyclonic storms, 6 very severe cyclonic storms, 3 extremely severe cyclonic storms, and 1 super cyclonic storm, Kyarr, the first since Cyclone Gonu in 2007. Additionally, it was also the third-costliest season recorded in the North Indian Ocean, only behind the 2020 and 2008 seasons.

The 2020 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was the costliest North Indian Ocean cyclone season on record, mostly due to Cyclone Amphan. The North Indian Ocean cyclone season has no official bounds, but cyclones tend to form between April and November, with peaks in late April to May and October to November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean. The season began on May 16 with the designation of Depression BOB 01 in the Bay of Bengal, which later became Amphan. Cyclone Amphan was the strongest storm in the Bay of Bengal in 21 years and would break Nargis of 2008's record as the costliest storm in the North Indian Ocean. The season concluded with the dissipation of Cyclone Burevi on December 5. Overall, the season was slightly above average, seeing the development of five cyclonic storms.

The 2021 North Indian Ocean cyclone season is an ongoing event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation. The North Indian Ocean cyclone season has no official bounds, but cyclones tend to form between April and December, peaking between May to November. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean.

Very Severe Cyclonic Storm Titli was a deadly and destructive tropical cyclone that caused extensive damage to Eastern India and Bangladesh in 2018. The fifth named storm to form in the 2018 North Indian Ocean cyclone season, the storm developed from a low-pressure area that formed in the Andaman Sea on October 6. Over the next two days, the low-pressure area entered the Bay of Bengal and became a depression on October 8, receiving the designation BOB 08 from the IMD. Afterward, the storm rapidly strengthened, becoming a Very Severe Cyclonic Storm on October 9, equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale (SSHWS). On October 11, Titli made landfall in eastern India at peak intensity, before weakening into a remnant low on the next day.

The 2013 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was an average season during the period of tropical cyclone formation in the North Indian Ocean. The season began in May with the formation of Cyclone Viyaru, which made landfall on Bangladesh, destroying more than 26,500 houses. After a period of inactivity, Cyclone Phailin formed in October, and became an extremely severe cyclonic storm. Additionally, it was a Category 5-equivalent cyclone on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. It then made landfall in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh and Odisha, becoming the most intense cyclone to strike the country since the 1999 Odisha cyclone. In November, cyclones Helen and Lehar formed, and they both made landfall in Andhra Pradesh just one week away from each other. The latter also affected the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Cyclones Gulab and Shaheen were two related, consecutive tropical cyclones that caused considerable damage to South and West Asia. Gulab impacted eastern India, while Shaheen impacted Pakistan, Iran, Oman and the United Arab Emirates. Gulab was the third named storm of the 2021 North Indian Ocean cyclone season, as well as the fourth named storm of the season after its reformation in the Arabian Sea as Shaheen. The cyclone's origins can be traced back to a low-pressure area situated over the Bay of Bengal on September 24. The system quickly organized, with the India Meteorological Department (IMD) upgrading the system to a depression on the same day. On the next day, the system strengthened into a Cyclonic Storm, and the IMD assigned it the name Gulab. On September 26, Gulab made landfall in India's Andhra Pradesh but weakened overland, before degenerating into a remnant low on September 28. The system continued moving westward, emerging into the Arabian Sea on September 29, before regenerating into a depression early on September 30. Early on October 1, the system restrengthened into a Cyclonic Storm, which the IMD named Shaheen. The system gradually strengthened as it entered the Gulf of Oman. While slowly moving westward, the storm turned southwestward, subsequently making an extremely rare landfall in Oman on October 3, as a Category 1-equivalent cyclone. Shaheen then rapidly weakened, before dissipating the next day.