Related Research Articles

In phonetics, a nasal, also called a nasal occlusive or nasal stop in contrast with an oral stop or nasalized consonant, is an occlusive consonant produced with a lowered velum, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. The vast majority of consonants are oral consonants. Examples of nasals in English are, and, in words such as nose, bring and mouth. Nasal occlusives are nearly universal in human languages. There are also other kinds of nasal consonants in some languages.

Chechen is a Northeast Caucasian language spoken by approximately 1.5 million people, mostly in the Chechen Republic and by members of the Chechen diaspora throughout Russia and the rest of Europe, Jordan, Central Asia and Georgia.

Pharyngealization is a secondary articulation of consonants or vowels by which the pharynx or epiglottis is constricted during the articulation of the sound.

Taa, also known as ǃXóõ, is a Tuu language notable for its large number of phonemes, perhaps the largest in the world. It is also notable for having perhaps the heaviest functional load of click consonants, with one count finding that 82% of basic vocabulary items started with a click. Most speakers live in Botswana, but a few hundred live in Namibia. The people call themselves ǃXoon or ʼNǀohan, depending on the dialect they speak. The Tuu languages are one of the three traditional language families that make up the Khoisan languages.

Naro, also Nharo, is a Khoe language spoken in Ghanzi District of Botswana and in eastern Namibia. It is probably the most-spoken of the Tshu–Khwe languages. Naro is a trade language among speakers of different Khoe languages in Ghanzi District. There exists a dictionary.

Gǀui or Gǀwi is a Khoe dialect of Botswana with 2,500 speakers. It is part of the Gǁana dialect cluster, and is closely related to Naro. It has a number of loan words from ǂʼAmkoe. Gǀui, ǂʼAmkoe, and Taa form the core of the Kalahari Basin sprachbund, and share a number of characteristic features, including extremely large consonant inventories.

The Sikkimese language, also called Sikkimese, Bhutia, or Drenjongké, Dranjoke, Denjongka, Denzongpeke and Denzongke, belongs to the Tibeto-Burman languages. It is spoken by the Bhutia in Sikkim, India and in parts of Province No. 1, Nepal. The Sikkimese people refer to their own language as Drendzongké and their homeland as Drendzong. Up until 1975 Sikkimese did not have a written language. After gaining Indian Statehood the language was introduced as a school subject in Sikkim and the written language was developed.

Guéré (Gere), also called Wè (Wee), is a Kru language spoken by over 300,000 people in the Dix-Huit Montagnes and Moyen-Cavally regions of Ivory Coast.

Khwarshi is a Northeast Caucasian language spoken in the Tsumadinsky-, Kizilyurtovsky- and Khasavyurtovsky districts of Dagestan by the Khwarshi people. The exact number of speakers is not known, but the linguist Zaira Khalilova, who has carried out fieldwork in the period from 2005 to 2009, gives the figure 8,500. Other sources give much lower figures, such as Ethnologue with the figure 1,870 and the latest population census of Russia with the figure 1,872. The low figures are because many Khwarshi have registered themselves as being Avar speakers, because Avar is their literary language.

The phonology of Sesotho and those of the other Sotho–Tswana languages are radically different from those of "older" or more "stereotypical" Bantu languages. Modern Sesotho in particular has very mixed origins inheriting many words and idioms from non-Sotho–Tswana languages.

The Owa language is one of the languages of Solomon Islands. It is part of the same dialect continuum as Kahua, and shares the various alternate names of that dialect.

Urhobo is a South-Western Edoid language spoken by the Urhobo people of southern Nigeria.

The Nukak language is a language of uncertain classification, perhaps part of the macrofamily Puinave-Maku. It is very closely related to Kakwa.

Moloko (Məlokwo) is an Afro-Asiatic language spoken in northern Cameroon.

Ndrumbea, variously spelled Ndumbea, Dubea, Drubea and Païta, is a New Caledonian language that gave its name to the capital of New Caledonia, Nouméa, and the neighboring town of Dumbéa. It has been displaced to villages outside the capital, with fewer than a thousand speakers remaining. Gordon (1995) estimates that there may only be two or three hundred. The Dubea are the people; the language has been called Naa Dubea "language of Dubea".

Fulniô, or Yatê, is a language isolate of Brazil, and the only indigenous language remaining in the northeastern part of that country. The two dialects, Fulniô and Yatê, are very close. The Fulniô dialect is used primarily during a three-month religious retreat. Today, the language is spoken in Águas Belas, Pernambuco.

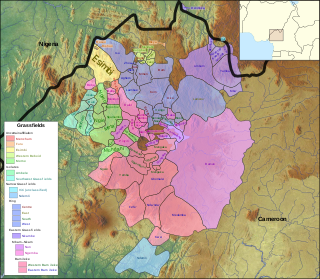

Babanki, or Kejom, is the traditional language of the Kejom people of the Western Highlands of Cameroon.

Chemnitz dialect is a distinct German dialect of the city of Chemnitz and an urban variety of Vorerzgebirgisch, a variant of Upper Saxon German.

Medumba phonology is the way in which the Medumba language is pronounced. It deals with phonetics, phonotactics and their variation across different dialects of Medumba.

References

- ↑ Yocoboué Dida at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Lakota Dida at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Gaɓogbo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)