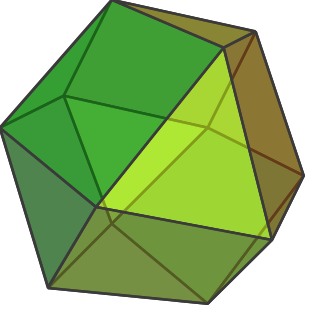

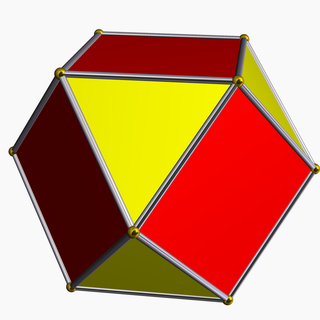

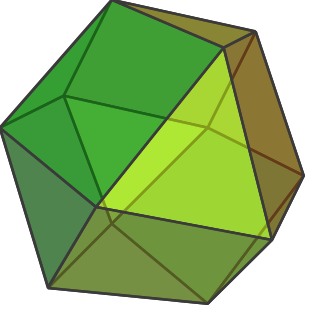

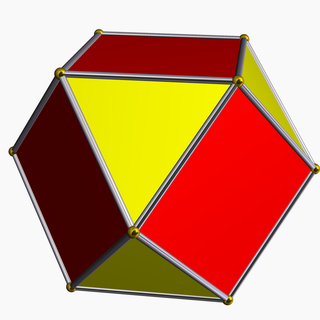

A cuboctahedron is a polyhedron with 8 triangular faces and 6 square faces. A cuboctahedron has 12 identical vertices, with 2 triangles and 2 squares meeting at each, and 24 identical edges, each separating a triangle from a square. As such, it is a quasiregular polyhedron, i.e., an Archimedean solid that is not only vertex-transitive but also edge-transitive. It is radially equilateral. Its dual polyhedron is the rhombic dodecahedron.

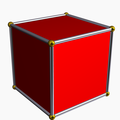

In geometry, a cube is a three-dimensional solid object bounded by six square faces. It has twelve edges and eight vertices. It can be represented as a rectangular cuboid with six square faces, or a parallelepiped with equal edges. It is an example of many type of solids: Platonic solid, regular polyhedron, parallelohedron, zonohedron, and plesiohedron. The dual polyhedron of a cube is the regular octahedron.

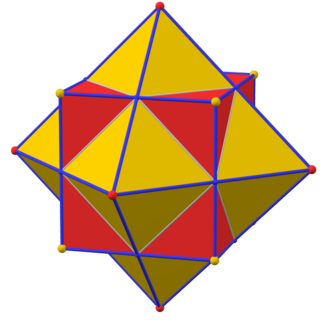

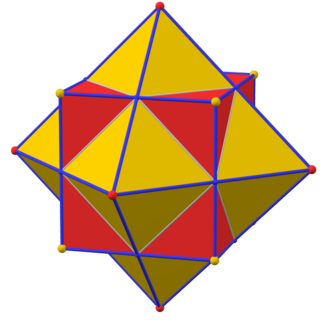

In geometry, every polyhedron is associated with a second dual structure, where the vertices of one correspond to the faces of the other, and the edges between pairs of vertices of one correspond to the edges between pairs of faces of the other. Such dual figures remain combinatorial or abstract polyhedra, but not all can also be constructed as geometric polyhedra. Starting with any given polyhedron, the dual of its dual is the original polyhedron.

In geometry, an icosidodecahedron or pentagonal gyrobirotunda is a polyhedron with twenty (icosi) triangular faces and twelve (dodeca) pentagonal faces. An icosidodecahedron has 30 identical vertices, with two triangles and two pentagons meeting at each, and 60 identical edges, each separating a triangle from a pentagon. As such, it is one of the Archimedean solids and more particularly, a quasiregular polyhedron.

In geometry, a polyhedron is a three-dimensional figure with flat polygonal faces, straight edges and sharp corners or vertices.

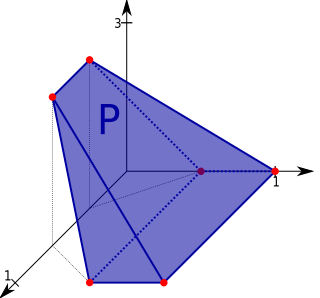

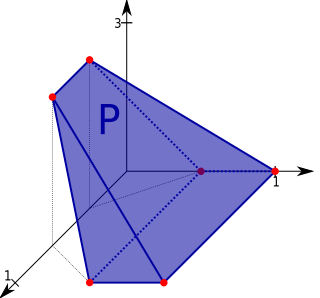

In geometry, a 4-polytope is a four-dimensional polytope. It is a connected and closed figure, composed of lower-dimensional polytopal elements: vertices, edges, faces (polygons), and cells (polyhedra). Each face is shared by exactly two cells. The 4-polytopes were discovered by the Swiss mathematician Ludwig Schläfli before 1853.

In geometry, the truncated icosahedron is a polyhedron that can be constructed by truncating all of the regular icosahedron's vertices. Intuitively, it may be regarded as footballs that are typically patterned with white hexagons and black pentagons. It can be found in the application of geodesic dome structures such as those whose architecture Buckminster Fuller pioneered are often based on this structure. It is an example of an Archimedean solid, as well as a Goldberg polyhedron.

In solid geometry, a face is a flat surface that forms part of the boundary of a solid object; a three-dimensional solid bounded exclusively by faces is a polyhedron. A face can be finite like a polygon or circle, or infinite like a half-plane or plane.

In geometry, the truncated tetrahedron is an Archimedean solid. It has 4 regular hexagonal faces, 4 equilateral triangle faces, 12 vertices and 18 edges. It can be constructed by truncating all 4 vertices of a regular tetrahedron.

In geometry, a polytope or a tiling is isogonal or vertex-transitive if all its vertices are equivalent under the symmetries of the figure. This implies that each vertex is surrounded by the same kinds of face in the same or reverse order, and with the same angles between corresponding faces.

In geometry, a net of a polyhedron is an arrangement of non-overlapping edge-joined polygons in the plane which can be folded to become the faces of the polyhedron. Polyhedral nets are a useful aid to the study of polyhedra and solid geometry in general, as they allow for physical models of polyhedra to be constructed from material such as thin cardboard.

A convex polytope is a special case of a polytope, having the additional property that it is also a convex set contained in the -dimensional Euclidean space . Most texts use the term "polytope" for a bounded convex polytope, and the word "polyhedron" for the more general, possibly unbounded object. Others allow polytopes to be unbounded. The terms "bounded/unbounded convex polytope" will be used below whenever the boundedness is critical to the discussed issue. Yet other texts identify a convex polytope with its boundary.

In Euclidean geometry, rectification, also known as critical truncation or complete-truncation, is the process of truncating a polytope by marking the midpoints of all its edges, and cutting off its vertices at those points. The resulting polytope will be bounded by vertex figure facets and the rectified facets of the original polytope.

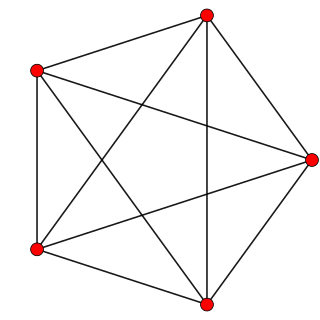

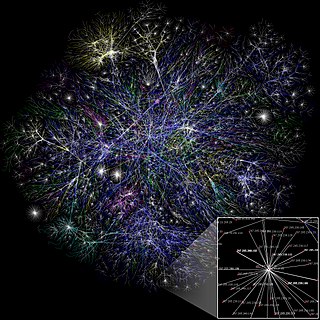

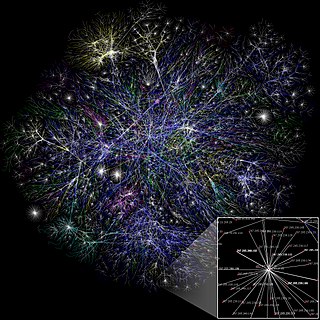

Geometric graph theory in the broader sense is a large and amorphous subfield of graph theory, concerned with graphs defined by geometric means. In a stricter sense, geometric graph theory studies combinatorial and geometric properties of geometric graphs, meaning graphs drawn in the Euclidean plane with possibly intersecting straight-line edges, and topological graphs, where the edges are allowed to be arbitrary continuous curves connecting the vertices; thus, it can be described as "the theory of geometric and topological graphs". Geometric graphs are also known as spatial networks.

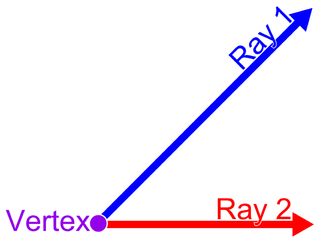

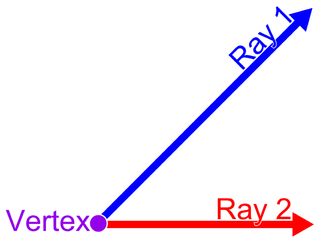

In geometry, a vertex is a point where two or more curves, lines, or edges meet or intersect. As a consequence of this definition, the point where two lines meet to form an angle and the corners of polygons and polyhedron are vertices.

Polyhedral combinatorics is a branch of mathematics, within combinatorics and discrete geometry, that studies the problems of counting and describing the faces of convex polyhedra and higher-dimensional convex polytopes.

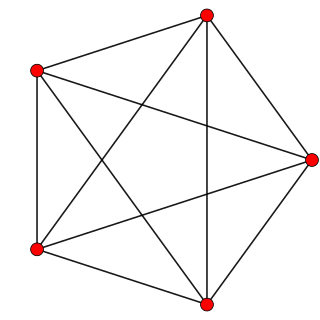

In polyhedral combinatorics, a branch of mathematics, Steinitz's theorem is a characterization of the undirected graphs formed by the edges and vertices of three-dimensional convex polyhedra: they are exactly the 3-vertex-connected planar graphs. That is, every convex polyhedron forms a 3-connected planar graph, and every 3-connected planar graph can be represented as the graph of a convex polyhedron. For this reason, the 3-connected planar graphs are also known as polyhedral graphs.

In geometric graph theory, a branch of mathematics, a polyhedral graph is the undirected graph formed from the vertices and edges of a convex polyhedron. Alternatively, in purely graph-theoretic terms, the polyhedral graphs are the 3-vertex-connected, planar graphs.

In polyhedral combinatorics, a branch of mathematics, Balinski's theorem is a statement about the graph-theoretic structure of three-dimensional convex polyhedra and higher-dimensional convex polytopes. It states that, if one forms an undirected graph from the vertices and edges of a convex d-dimensional convex polyhedron or polytope, then the resulting graph is at least d-vertex-connected: the removal of any d − 1 vertices leaves a connected subgraph. For instance, for a three-dimensional polyhedron, even if two of its vertices are removed, for any pair of vertices there will still exist a path of vertices and edges connecting the pair.

In geometry, a toroidal polyhedron is a polyhedron which is also a toroid, having a topological genus of 1 or greater. Notable examples include the Császár and Szilassi polyhedra.