Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he is regarded as one of the main founders of modern bacteriology. As such he is popularly nicknamed the father of microbiology, and as the father of medical bacteriology. His discovery of the anthrax bacterium in 1876 is considered as the birth of modern bacteriology. Koch used his discoveries to establish that germs "could cause a specific disease" and directly provided proofs for the germ theory of diseases, therefore creating the scientific basis of public health, saving millions of lives. For his life's work Koch is seen as one of the founders of modern medicine.

A Petri dish is a shallow transparent lidded dish that biologists use to hold growth medium in which cells can be cultured, originally, cells of bacteria, fungi and small mosses. The container is named after its inventor, German bacteriologist Julius Richard Petri. It is the most common type of culture plate. The Petri dish is one of the most common items in biology laboratories and has entered popular culture. The term is sometimes written in lower case, especially in non-technical literature.

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks, the mortality rate approaches 10%. Signs and symptoms may vary from mild to severe, and usually start two to five days after exposure. Symptoms often develop gradually, beginning with a sore throat and fever. In severe cases, a grey or white patch develops in the throat, which can block the airway, and create a barking cough similar to what is observed in croup. The neck may also swell in part due to the enlargement of the facial lymph nodes. Diphtheria can also involve the skin, eyes, or genitals, and can cause complications, including myocarditis, inflammation of nerves, kidney problems, and bleeding problems due to low levels of platelets.

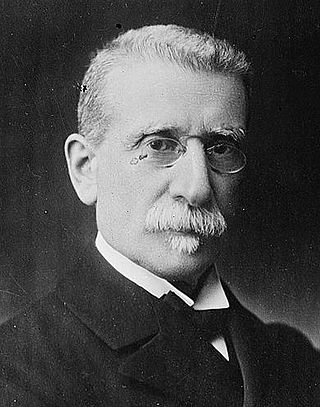

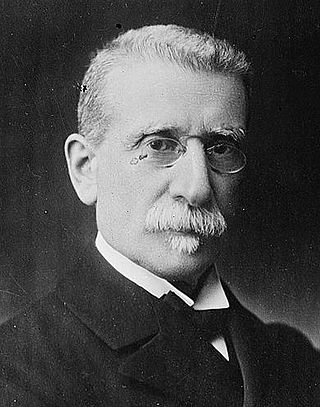

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran was a French physician who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907 for his discoveries of parasitic protozoans as causative agents of infectious diseases such as malaria and trypanosomiasis. Following his father, Louis Théodore Laveran, he took up military medicine as his profession. He obtained his medical degree from University of Strasbourg in 1867.

Brigadier General George Miller Sternberg was a U.S. Army physician who is considered the first American bacteriologist, having written Manual of Bacteriology (1892). After he survived typhoid and yellow fever, Sternberg documented the cause of malaria (1881), discovered the cause of lobar pneumonia (1881), and confirmed the roles of the bacilli of tuberculosis and typhoid fever (1886).

The Pasteur Institute is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines for anthrax and rabies. The institute was founded on 4 June 1887 and inaugurated on 14 November 1888.

Johannes Andreas Grib Fibiger was a Danish physician and professor of anatomical pathology at the University of Copenhagen. He was the recipient of the 1926 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for his discovery of the Spiroptera carcinoma". He demonstrated that the roundworm which he called Spiroptera carcinoma could cause stomach cancer in rats and mice. His experimental results were later proven to be a case of mistaken conclusion. Erling Norrby, who had served as the Permanent Secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and Professor and Chairman of Virology at the Karolinska Institute, declared Fibiger's Nobel Prize as "one of the biggest blunders made by the Karolinska Institute."

Friedrich August Johannes Loeffler was a German bacteriologist at the University of Greifswald.

Corynebacterium diphtheriae is the pathogenic bacterium that causes diphtheria. It is also known as the Klebs–Löffler bacillus, because it was discovered in 1884 by German bacteriologists Edwin Klebs (1834–1912) and Friedrich Löffler (1852–1915). The bacteria are usually harmless unless they are infected by a bacteriophage that carries a gene that gives rise to a toxin. This toxin causes the disease. Diphtheria is caused by the adhesion and infiltration of the bacteria into the mucosal layers of the body, primarily affecting the respiratory tract and the subsequent release of an endotoxin. The toxin has a localized effect on skin lesions, as well as a metastatic, proteolytic effects on other organ systems in severe infections. Originally a major cause of childhood mortality, diphtheria has been almost entirely eradicated due to the vigorous administration of the diphtheria vaccination in the 1910s.

Corynebacterium is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria and most are aerobic. They are bacilli (rod-shaped), and in some phases of life they are, more specifically, club-shaped, which inspired the genus name.

Lysogeny, or the lysogenic cycle, is one of two cycles of viral reproduction. Lysogeny is characterized by integration of the bacteriophage nucleic acid into the host bacterium's genome or formation of a circular replicon in the bacterial cytoplasm. In this condition the bacterium continues to live and reproduce normally, while the bacteriophage lies in a dormant state in the host cell. The genetic material of the bacteriophage, called a prophage, can be transmitted to daughter cells at each subsequent cell division, and later events can release it, causing proliferation of new phages via the lytic cycle.

Carl Friedländer was a German pathologist and microbiologist who helped discover the bacterial cause of pneumonia in 1882. He also first described thromboangiitis obliterans.

George Henry Falkiner Nuttall FRS was an American-British bacteriologist who contributed much to the knowledge of parasites and of insect carriers of diseases. He made significant innovative discoveries in immunology, about life under aseptic conditions, in blood chemistry, and about diseases transmitted by arthropods, especially ticks. He carried out investigations into the distribution of Anopheline mosquitoes in England in relation to the previous prevalence of malaria there. With William Welch he identified the organism responsible for causing gas gangrene.

Richard Friedrich Johannes Pfeiffer FRS was a German physician and bacteriologist. Pfeiffer was born to Otto Pfeiffer, a German pastor of the local Evangelical parish, and Natalia née Jüttner, in Treustädt, Province of Posen (Prussia), and died in Bad Landeck.

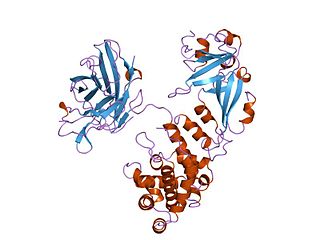

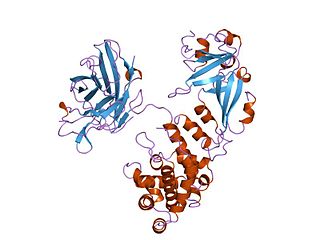

Diphtheria toxin is an exotoxin secreted mainly by Corynebacterium diphtheriae but also by Corynebacterium ulcerans and Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, the pathogenic bacterium that causes diphtheria. The toxin gene is encoded by a prophage called corynephage β. The toxin causes the disease in humans by gaining entry into the cell cytoplasm and inhibiting protein synthesis.

William Hallock Park was an American bacteriologist and laboratory director at the New York City Board of Health, Division of Pathology, Bacteriology, and Disinfection from 1893 to 1936.

Ettore Marchiafava was an Italian physician, pathologist and neurologist. He spent most of his career as professor of medicine at the University of Rome. His works on malaria laid down the foundation for modern malariology. He and Angelo Celli were the first to elucidate living malarial parasites in human blood, and able to distinguish the protozoan parasites responsible for tertian and benign malaria. In 1885 they gave the formal scientific name Plasmodium for these parasites. They also discovered meningococcus as the causative agent of cerebral and spinal meningitis. Marchiafava was the first to describe syphilitic cerebral arteritis and degeneration of brain in an alcoholic patient, which is now eponymously named Marchiafava's disease. He gave a complete description of a genetic disease of blood now known Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria or sometimes Strübing-Marchiafava-Micheli syndrome, in honour of the pioneer scientists. He was personal physician to three successive popes and also to House of Savoy. In 1913 he was elected to Senate of the Kingdom of Italy. He founded the first Italian anti-tuberculosis sanatorium at Rome. He was elected member of the Accademia dei Lincei, becoming its vice-president in 1933.

Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli was an Italian physician known for his works in pathology and hygiene. He studied for his medical degree at the University of Pisa. He was trained in pathology under the German pathologist Rudolf Virchow. He worked in medical services at Florence, Palermo, and Rome. He was Chair of Pathology at the Sapienza University of Rome. He was known to the public for his service during cholera outbreak and in establishing hospitals, particularly the Institute for Experimental Hygiene in Rome. He was elected to Italian Senate during 1892–1893. He, with Edwin Klebs, discovered that typhoid and diphtheria were caused by bacteria. However, they made a mistake in declaring that a bacterium was also responsible for malaria.

John Howard Mueller was an American biochemist, pathologist, and bacteriologist. He is known as the discoverer of the amino acid methionine in 1921, and as the co-developer, with Jane Hinton, of the eponymous Mueller–Hinton agar.

George Stuart Graham-Smith was a British pathologist and zoologist particularly noted for his work on flies, both as disease vectors, and as organisms of interest in their own right.