Related Research Articles

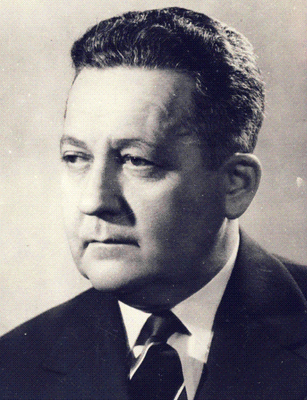

Ion Gheorghe Iosif Maurer was a Romanian communist politician and lawyer, and the 49th Prime Minister of Romania. He is the longest serving Prime Minister in the history of Romania.

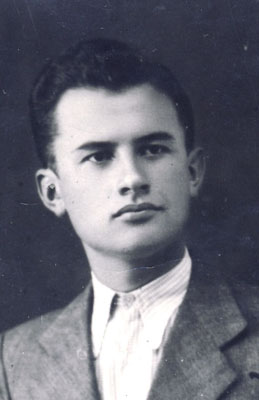

Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu was a Romanian communist politician and leading member of the Communist Party of Romania (PCR), also noted for his activities as a lawyer, sociologist and economist. For a while, he was a professor at the University of Bucharest. Pătrășcanu rose to a government position before the end of World War II and, after having disagreed with Stalinist tenets on several occasions, eventually came into conflict with the Romanian Communist government of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. He became a political prisoner and was ultimately executed. Fourteen years after Pătrășcanu's death, Romania's new communist leader, Nicolae Ceaușescu, endorsed his rehabilitation as part of a change in policy.

Vasile Luca was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian and Soviet communist politician, a leading member of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) from 1945 and until his imprisonment in the 1950s. Noted for his activities in the Ukrainian SSR in 1940–1941, he sided with Ana Pauker during World War II, and returned to Romania to serve as the minister of finance and one of the most recognizable leaders of the Communist regime. Luca's downfall, coming at the end of a conflict with Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, signaled that of Pauker.

Gheorghe Apostol was a Romanian politician, deputy Prime Minister of Romania and a former leader of the Communist Party (PCR), noted for his rivalry with Nicolae Ceaușescu.

The Ploughmen's Front was a Romanian left-wing agrarian-inspired political organisation of ploughmen, founded at Deva in 1933 and led by Petru Groza. At its peak in 1946, the Front had over 1 million members.

Constantin Pîrvulescu was a Romanian communist politician, one of the founders of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR), who, as time went on, became an active opponent of leader Nicolae Ceaușescu. Briefly expelled from the Party in 1960, he was re-admitted and elected to the Party Revision Committee in 1974.

Grigore Preoteasa was a Romanian communist activist, journalist and politician, who served as Communist Romania's Minister of Foreign Affairs between October 4, 1955, and the time of his death.

Miron Constantinescu was a Romanian communist politician, a leading member of the Romanian Communist Party, as well as a Marxist sociologist, historian, academic, and journalist. Initially close to Communist Romania's leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, he became increasingly critical of the latter's Stalinist policies during the 1950s, and was sidelined together with Iosif Chișinevschi. Reinstated under Nicolae Ceauşescu, he became a member of the Romanian Academy.

Lena Constante was a Romanian artist, essayist, and memoirist, known for her work in stage design and tapestry. A family friend of Communist Party politician Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu, she was arrested by the Communist regime following the conflict between Pătrășcanu and Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. She was indicted in his trial and spent twelve years as a political prisoner.

Alexandru Nicolschi was a Romanian communist activist, Soviet agent and officer, and Securitate chief under the Communist regime. Active until 1961, he was one of the most recognizable leaders of violent political repression.

Ștefan Foriș was a Hungarian and Romanian communist journalist who served as general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party between December 1940 and April 1944. Born a Transylvanian Csángó and an Austro-Hungarian subject, he saw action with the Hungarian Landwehr throughout World War I. While training in mathematics at Eötvös Loránd University, he affiliated with the Galileo Circle and, moving to the far-left, entered the Hungarian Communist Party in late 1918. During the brief existence of a Hungarian Soviet Republic, he joined the war against Romania (1919), but subsequently opted to settle in the Romanian Kingdom, at Brașov. Foriș emerged as a local leader of the Socialist Party, largely failing at convincing his subordinates to join the PCR upon its creation (1921). He took up underground work even before the PCR was formally outlawed, while establishing his public profile as an accountant and a correspondent for moderate left-wing newspapers—including Adevărul and Facla.

Gheorghe Pintilie was a Soviet and Romanian intelligence agent and political assassin, who served as first head of the Securitate (1948–1958). Born as a subject of the Russian Empire in Tiraspol, he was briefly employed as a manual laborer, and trained as a locksmith, before joining the Red Army cavalry and seeing action in the Russian Civil War. The NKVD shortlisted him for espionage missions in the 1920s, and in 1928 sent him on for such clandestine work in the Kingdom of Romania. Bodnarenko was apprehended there some nine years later, and sentenced to a twenty-years' imprisonment. While at Doftana, he became the ringleader of imprisoned Soviet spies, together with whom he joined the Romanian Communist Party (PCR). He expressed his loyalty toward Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, the jailed communist and emerging factional leader; their tight political camaraderie lasted into the late 1950s.

Valter or Walter Roman, born Ernst or Ernő Neuländer, was a Romanian communist activist and soldier. During his lifetime, Roman was active inside the Romanian, Czechoslovakian, French, and Spanish Communist parties as well as being a Comintern cadre. He started his military career as a volunteer in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War, and rose to prominence in Communist Romania, as a high-level politician and military official.

Emil Bodnăraș was a Romanian communist politician, an army officer, and a Soviet agent, who had considerable influence in the Romanian People's Republic.

Ion Vincze was a Romanian communist politician and diplomat. An activist of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR), he was married to Constanța Crăciun, herself a prominent member of the party.

Petre Borilă was a Romanian communist politician who briefly served as Vice-Premier under the Communist regime. A member of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) since his late teens, he was a political commissar in the Spanish Civil War and a Comintern cadre afterwards, spending World War II in exile in the Soviet Union. Borilă returned to Romania during the late 1940s, and rose to prominence under Communist rule, when he was a member of the PCR's Central Committee and Politburo.

Alexandru Drăghici was a Romanian communist activist and politician. He was Interior Minister in 1952 and from 1957 to 1965, and State Security Minister from 1952 to 1957. In these capacities, he exercised control over the Securitate secret police during a period of active repression against other Communist Party members, anti-communist resistance members and ordinary citizens.

Leonte Răutu was a Bessarabian-born Romanian communist activist and propagandist, who served as deputy prime minister in 1969–1972. He was chief ideologist of the Romanian Communist Party during the rule of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, and one of his country's few high-ranking communists to have studied Marxism from the source. Răutu was of Jewish origin, though he embraced atheism and anti-Zionism. His adventurous youth, with two prison terms served for illegal political activity, culminated in his self-exile to the Soviet Union, where he spent the larger part of World War II. Specializing in agitprop and becoming friends with communist militant Ana Pauker, he joined the Romanian section of Radio Moscow.

Mișu Dulgheru was a Romanian communist activist and spy. A clerk by trade, he rose through the secret police as the Romanian Communist Party consolidated its hold on power between 1944 and 1947, while from 1948 through 1952, he played an important role as an officer in the new Securitate. Subsequently, arrested as part of a wider purge, he was released after an investigation lasting over two years, but never regained his earlier prestige. Late in life, he left his native country for Israel and, later, Canada.

Remus Koffler was a Romanian communist activist who, during the 1930s and 1940s, helped assure financing for the Romanian Communist Party. Arrested in 1949 as an inconvenient survivor, he was executed over four years later.

References

- Introduction to Gad Calmgran, "Boris I, regele Andorrei" ("Boris I, King of Andorra"), in Magazin Istoric, August 1997

- (in Romanian) Calmanovici's letter to the engineer Emil Herstein, sent from prison (1955), at the Sfera Politicii archive; retrieved July 29, 2007

- Lavinia Betea,

- (in Romanian) "Procese politice" ("Political Trials"), in Jurnalul Național , June 12, 2006

- (in Romanian) "«Recunoștința» Partidului față de cei care l-au subvenționat" ("The Party's «Gratitude» towards Those Who Had Financed It"), in Magazin Istoric, August 1997; retrieved July 29, 2007

- "Testamentul lui Foriș" ("Foriș' Last Will"), in Magazin Istoric, April 1997

- (in Romanian) Sanda Golopenția, "Introducere la Ultima carte de Anton Golopenția (Anchetatorii)" ("Introduction to Anton Golopenția's Ultima carte (The Inquisitors)"), at Memoria.ro; retrieved July 29, 2007

- Robert Levy, Ana Pauker: The Rise and Fall of a Jewish Communist, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2001. ISBN 0-520-22395-0

- Vladimir Tismăneanu, Stalinism pentru eternitate, Polirom, Iași, 2005. ISBN 973-681-899-3 (translation of Stalinism for All Seasons: A Political History of Romanian Communism, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2003. ISBN 0-520-23747-1)