Akkadian is an extinct East Semitic language that was spoken in ancient Mesopotamia from the third millennium BC until its gradual replacement in common use by Old Aramaic among Assyrians and Babylonians from the 8th century BC.

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform scripts are marked by and named for the characteristic wedge-shaped impressions which form their signs. Cuneiform is the earliest known writing system and was originally developed to write the Sumerian language of southern Mesopotamia.

Old Persian is one of two directly attested Old Iranian languages and is the ancestor of Middle Persian. Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native speakers as ariya (Iranian). Old Persian is close to both Avestan and the language of the Rig Veda, the oldest form of the Sanskrit language. All three languages are highly inflected.

Khwārezmian is an extinct Eastern Iranian language closely related to Sogdian. The language was spoken in the area of Khwarezm (Chorasmia), centered in the lower Amu Darya south of the Aral Sea.

Middle Persian, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasanian Empire. For some time after the Sasanian collapse, Middle Persian continued to function as a prestige language. It descended from Old Persian, the language of the Achaemenid Empire and is the linguistic ancestor of Modern Persian, the official language of Iran, Afghanistan (Dari) and Tajikistan (Tajik).

Middle Persian literature is the corpus of written works composed in Middle Persian, that is, the Middle Iranian dialect of Persia proper, the region in the south-western corner of the Iranian plateau. Middle Persian was the prestige dialect during the era of Sasanian dynasty. It is the largest source of Zoroastrian literature.

Frahang-i Oīm-Ēwak is an old Avestan-Middle Persian dictionary. It is named with the two first words of the dictionary: oīm in Avestan means 'one' and ēwak is its Pahlavi equivalent. It gives the Pahlavi meanings of about 880 Avestan words, either by one word or one phrase or by explaining it.

The Avestan alphabet is a writing system developed during Iran's Sasanian era (226–651 CE) to render the Avestan language.

The Parthian language, also known as Arsacid Pahlavi and Pahlawānīg, is an extinct ancient Northwestern Iranian language once spoken in Parthia, a region situated in present-day northeastern Iran and Turkmenistan. Parthian was the language of state of the Arsacid Parthian Empire, as well as of its eponymous branches of the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia, Arsacid dynasty of Iberia, and the Arsacid dynasty of Caucasian Albania.

The Book of Arda Viraf is a Zoroastrian text written in Middle Persian. It contains about 8,800 words. It describes the dream-journey of a devout Zoroastrian through the next world. The text assumed its definitive form in the 9th-10th centuries after a series of redactions and it is probable that the story was an original product of 9th-10th century Pars.

Pahlavi is a particular, exclusively written form of various Middle Iranian languages. The essential characteristics of Pahlavi are:

The Jamasp Nameh is a Middle Persian book of revelations. In an extended sense, it is also a primary source on Medieval Zoroastrian doctrine and legend. The work is also known as the Ayādgār ī Jāmāspīg or Ayātkār-ī Jāmāspīk, meaning "[In] Memoriam of Jamasp".

Pazend or Pazand is one of the writing systems used for the Middle Persian language. It was based on the Avestan alphabet, a phonetic alphabet originally used to write Avestan, the language of the Avesta, the primary sacred texts of Zoroastrianism.

The Bundahishn is an encyclopedic collection of beliefs about Zoroastrian cosmology written in the Book Pahlavi script. The original name of the work is not known. It is one of the most important extant witnesses to Zoroastrian literature in the Middle Persian language.

Dingir ⟨𒀭⟩, usually transliterated DIĜIR, is a Sumerian word for 'god' or 'goddess'. Its cuneiform sign is most commonly employed as the determinative for religious names and related concepts, in which case it is not pronounced and is conventionally transliterated as a superscript ⟨d⟩, e.g. dInanna.

The Manichaean script is an abjad-based writing system rooted in the Semitic family of alphabets and associated with the spread of Manichaeism from southwest to central Asia and beyond, beginning in the third century CE. It bears a sibling relationship to early forms of the Pahlavi scripts, both systems having developed from the Imperial Aramaic alphabet, in which the Achaemenid court rendered its particular, official dialect of Aramaic. Unlike Pahlavi, the Manichaean script reveals influences from the Sogdian alphabet, which in turn descends from the Syriac branch of Aramaic. The Manichaean script is so named because Manichaean texts attribute its design to Mani himself. Middle Persian is written with this alphabet.

A Sumerogram is the use of a Sumerian cuneiform character or group of characters as an ideogram or logogram rather than a syllabogram in the graphic representation of a language other than Sumerian, such as Akkadian, Eblaite, or Hittite. This type of logogram characterized, to a greater or lesser extent, every adaptation of the original Mesopotamian cuneiform system to a language other than Sumerian. The frequency and intensity of their use varied depending on period, style, and genre. In the same way, a written Akkadian word that is used ideographically to represent a language other than Akkadian is known as an Akkadogram.

Zend or Zand is a Zoroastrian technical term for exegetical glosses, paraphrases, commentaries and translations of the Avesta's texts. The term zand is a contraction of the Avestan language word zainti.

The Zand-i Wahman Yasn is a medieval Zoroastrian apocalyptical text in Middle Persian. It professes to be a prophetical work, in which Ahura Mazda gives Zoroaster an account of what was to happen to the behdin and their religion in the future. The oldest surviving manuscript is from about 1400, but the text itself is older, written and edited over the course of several generations.

Heterogram is a term used mostly in the philology of Akkadian, and Pahlavi texts containing borrowings from Sumerian and Aramaic respectively. It refers to a special type of logogram or ideogram borrowed from another language to represent either a sound or meaning in the matrix language. It is now commonly accepted that they do not represent true borrowings from the embedded language and instead came to represent a separate register of orthographic archaisms.

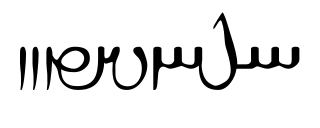

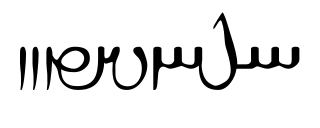

![]()

![]()

![]() but understood in Iran to be the sign for 'shāh'.

but understood in Iran to be the sign for 'shāh'.