The metre or meter is the base unit of length in the International System of Units (SI). The SI unit symbol is m.

Antonio de Ulloa y de la Torre-Giralt, FRS, FRSA, KOS was a Spanish naval officer, scientist, and administrator. At the age of nineteen, he joined the French Geodesic Mission to what is now the country of Ecuador. That mission took more than eight years to complete its work, during which time Ulloa made many astronomical, natural, and social observations in South America. The reports of Ulloa's findings earned him an international reputation as a leading savant. Those reports include the first published observations of the metal platinum, later identified as a new chemical element. Ulloa was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1746, and as a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1751.

Geodesy (/dʒiːˈɒdɪsi/), also named geodetics, is the scientific discipline that deals with the measurement and representation of the Earth. The history of geodesy began in pre-scientific antiquity and blossomed during the Age of Enlightenment.

The year 1749 in science and technology involved some significant events.

Pierre Bouguer was a French mathematician, geophysicist, geodesist, and astronomer. He is also known as "the father of naval architecture".

Charles Marie de La Condamine was a French explorer, geographer, and mathematician. He spent ten years in territory which is now Ecuador measuring the length of a degree latitude at the equator and preparing the first map of the Amazon region based on astronomical observations. Furthermore he was a contributor to the Encyclopédie.

The year 1735 in science and technology involved some significant events.

Pichincha is an active stratovolcano in the country of Ecuador. The capital Quito wraps around its eastern slopes.

Louis Godin was a French astronomer and member of the French Academy of Sciences. He worked in Peru, Spain, Portugal and France.

The Ciudad Mitad del Mundo is a tract of land owned by the prefecture of the province of Pichincha, Ecuador. It is located at San Antonio parish of the canton of Quito, 26 km (16 mi) north of the center of Quito. The grounds contain the Monument to the Equator, which highlights the exact location of the Equator and commemorates the eighteenth century Franco-Spanish Geodesic Mission which fixed its approximate location; they also contain the Museo Etnográfico Mitad del Mundo, Ethnographic Museum Middle of the Earth, a museum about the indigenous people ethnography of Ecuador.

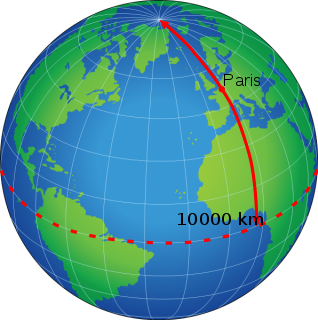

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.03″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world. The "Paris meridian arc" or "French meridian arc" is the name of the meridian arc measured along the Paris meridian.

A toise is a unit of measure for length, area and volume originating in pre-revolutionary France. In North America, it was used in colonial French establishments in early New France, French Louisiana (Louisiane), Acadia (Acadie) and Quebec. The related toesa was used in Portugal, Brazil and other parts of the Portuguese Empire until the adoption of the Metric system.

José Antonio de Mendoza Caamaño y Sotomayor, 3rd Marquis of Villagarcía de Arousa was a Spanish colonial administrator in the Americas. From February 4, 1736 to December 15, 1745 he was Viceroy of Peru.

Pedro Vicente Maldonado y Flores, was an Ecuadorian scientist who collaborated with the members of the French Geodesic Mission. As well as a physicist and a mathematician, Maldonado was an astronomer, topographer, and geographer.

Jorge Juan y Santacilia was a Spanish mathematician, scientist, naval officer, and mariner. He determined that the Earth is not perfectly spherical but is oblate, i.e. flattened at the poles. Juan also successfully measured the heights of the mountains of the Andes using a barometer.

A seconds pendulum is a pendulum whose period is precisely two seconds; one second for a swing in one direction and one second for the return swing, a frequency of 0.5 Hz.

Jean Godin des Odonais was a French cartographer and naturalist.

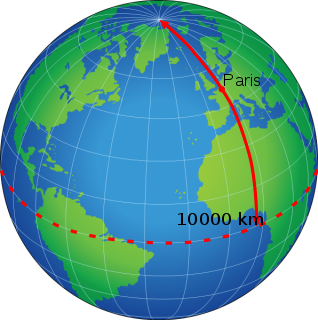

In geodesy, a meridian arc measurement is the distance between two points with the same longitude, i.e., a segment of a meridian curve or its length. Two or more such determinations at different locations then specify the shape of the reference ellipsoid which best approximates the shape of the geoid. This process is called the determination of the figure of the Earth. The earliest determinations of the size of a spherical Earth required a single arc. The latest determinations use astro-geodetic measurements and the methods of satellite geodesy to determine the reference ellipsoids.

The history of the metre starts with the scientific revolution that began with Nicolaus Copernicus's work in 1543. Increasingly accurate measurements were required, and scientists looked for measures that were universal and could be based on natural phenomena rather than royal decree or physical prototypes. Rather than the various complex systems of subdivision in use, they also preferred a decimal system to ease their calculations.

The French Geodesic Mission to Lapland was one of the two French Geodesic Mission carried out in 1736–1737 by the French Academy of Sciences for measuring the shape of the Earth. One expedition was sent to Ecuador to perform measurements near the Equator, another one was sent to Meänmaa to perform measurements near the Arctic Circle.