Andries van Wezel, latinised as Andreas Vesalius, was an anatomist and physician who wrote De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, which is considered one of the most influential books on human anatomy and a major advance over the long-dominant work of Galen. Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy. He was born in Brussels, which was then part of the Habsburg Netherlands. He was a professor at the University of Padua (1537–1542) and later became Imperial physician at the court of Emperor Charles V.

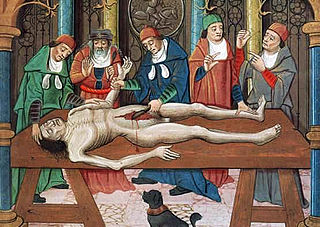

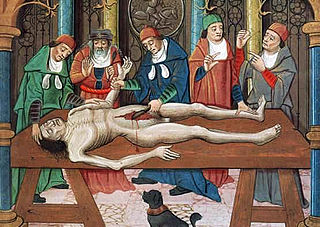

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of sacrificial victims to the sophisticated analyses of the body performed by modern anatomists and scientists. Written descriptions of human organs and parts can be traced back thousands of years to ancient Egyptian papyri, where attention to the body was necessitated by their highly elaborate burial practices.

Peyronie's disease is a connective tissue disorder involving the growth of fibrous plaques in the soft tissue of the penis. Specifically, scar tissue forms in the tunica albuginea, the thick sheath of tissue surrounding the corpora cavernosa, causing pain, abnormal curvature, erectile dysfunction, indentation, loss of girth and shortening.

Bartolomeo Eustachi, also known as Eustachio or by his Latin name of Bartholomaeus Eustachius, was an Italian anatomist and one of the founders of the science of human anatomy.

Julius Caesar Aranzi was a leading figure in the history of the science of human anatomy.

Girolamo Fabrici d'Acquapendente, also known as Girolamo Fabrizio or Hieronymus Fabricius, was a pioneering anatomist and surgeon known in medical science as "The Father of Embryology."

Matteo Realdo Colombo was an Italian professor of anatomy and a surgeon at the University of Padua between 1544 and 1559.

The University of Padua is an Italian public research university in Padua, Italy. It was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from the University of Bologna, who previously settled in Vicenza, thus, it is the second-oldest university in Italy, as well as the world's fifth-oldest surviving university.

Moulage is the art of applying mock injuries for the purpose of training emergency response teams and other medical and military personnel. Moulage may be as simple as applying pre-made rubber or latex "wounds" to a healthy "patient's" limbs, chest, head, etc., or as complex as using makeup and theatre techniques to provide elements of realism to the training simulation. The practice dates to at least the Renaissance, when wax figures were used for this purpose.

Giovanni Battista Morgagni was an Italian anatomist, generally regarded as the father of modern anatomical pathology, who taught thousands of medical students from many countries during his 56 years as Professor of Anatomy at the University of Padua.

Alessandro Achillini was an Italian philosopher and physician. He is known for the anatomic studies that he was able to publish, made possible by a 13th-century edict putatively by Emperor Frederick II allowing for dissection of human cadavers, and which previously had stimulated the anatomist Mondino de Luzzi at Bologna.

Antonio Scarpa was an Italian anatomist and professor.

Volcher Coiter was a Dutch anatomist who established the study of comparative osteology and first described cerebrospinal meningitis. He also studied the human eye and was able to demonstrate the replenishment of the aqueous humor. Coiter's muscle is a name sometimes used for the corrugator superciliaris that is involved in wrinkling of the eyebrow. He illustrated his works with his own meticulously detailed drawings.

Justus Ferdinand Christian Loder was a German anatomist and surgeon who was a native of Riga.

Johannes Baptista Montanus is the Latinized name of Giovanni Battista Monte, or Gian Battista da Monte, one of the leading Renaissance humanist physicians of Italy. Montanus promoted the revival of Greek medical texts and practice, producing revisions of Galen as well as of Islamic medical texts by Rhazes and Avicenna. He was himself a medical writer and was regarded as a second Galen.

An anatomy murder is a murder committed in order to use all or part of the cadaver for medical research or teaching. It is not a medicine murder because the body parts are not believed to have any medicinal use in themselves. The motive for the murder is created by the demand for cadavers for dissection, and the opportunity to learn anatomy and physiology as a result of the dissection. Rumors concerning the prevalence of anatomy murders are associated with the rise in demand for cadavers in research and teaching produced by the Scientific Revolution. During the 19th century, the sensational serial murders associated with Burke and Hare and the London Burkers led to legislation which provided scientists and medical schools with legal ways of obtaining cadavers. Rumors persist that anatomy murders are carried out wherever there is a high demand for cadavers. These rumors, like those concerning organ theft, are hard to substantiate, and may reflect continued, deep-held fears of the use of cadavers as commodities.

Giulio Cesare Casseri, also written as Giulio Casser, Giulio Casserio of Piacenza or Latinized as Iulius Casserius Placentinus, Giulio Casserio, was an Italian anatomist. He is best known for the books Tabulae anatomicae (1627) andDe Vocis Auditusque Organis. He was the first to describe the Circle of Willis.

Pieter Pauw, was a Dutch botanist and anatomist. He was a student of Hieronymus Fabricius. He was the first Anatomy Professor at University of Leiden.

The Anatomical Theatre of Padua, Northern Italy, is the first permanent anatomical theatre in the world. Still preserved in the Palazzo del Bo, it was inaugurated in 1595 by Girolamo Fabrici of Acquapendente, according to the project of Paolo Sarpi and Dario Varotari. This theatre constituted the model for the anatomical theatres built during the seventeenth century in the main universities of Europe: all would have been based on the Paduan archetype. It is the symbol of a successful period in the University of Padua's history, and it is considered one of the most important achievements for the study of anatomy during the sixteenth century.

Pedro Jimeno was a Valencian anatomist.