Roman roads were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. They provided efficient means for the overland movement of armies, officials, civilians, inland carriage of official communications, and trade goods. Roman roads were of several kinds, ranging from small local roads to broad, long-distance highways built to connect cities, major towns and military bases. These major roads were often stone-paved and metaled, cambered for drainage, and were flanked by footpaths, bridleways and drainage ditches. They were laid along accurately surveyed courses, and some were cut through hills or conducted over rivers and ravines on bridgework. Sections could be supported over marshy ground on rafted or piled foundations.

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. These points are usually on the surface of the Earth, and they are often used to establish maps and boundaries for ownership, locations, such as the designated positions of structural components for construction or the surface location of subsurface features, or other purposes required by government or civil law, such as property sales.

A palatine or palatinus is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman times. The term palatinus was first used in Ancient Rome for chamberlains of the Emperor due to their association with the Palatine Hill. The imperial palace guard, after the rise of Constantine I, were also called the Scholae Palatinae for the same reason. In the Early Middle Ages the title became attached to courts beyond the imperial one; one of the highest level of officials in the papal administration were called the judices palatini. Later the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties had counts palatine, as did the Holy Roman Empire. Related titles were used in Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, the German Empire, and the County of Burgundy, while England, Ireland, and parts of British North America referred to rulers of counties palatine as palatines.

Sextus Julius Frontinus was a prominent Roman civil engineer, author, soldier and senator of the late 1st century AD. He was a successful general under Domitian, commanding forces in Roman Britain, and on the Rhine and Danube frontiers. A novus homo, he was consul three times. Frontinus ably discharged several important administrative duties for Nerva and Trajan. However, he is best known to the post-Classical world as an author of technical treatises, especially De aquaeductu, dealing with the aqueducts of Rome.

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus was a reformist Roman politician and soldier who lived during the 2nd century BC. He is most famous for his tribunate for the years 123 and 122 BC, in which he proposed a wide set of laws, including laws to establish colonies outside of Italy, engage in further land reform, reform the judicial system and system for provincial assignments, and create a subsidised grain supply for Rome.

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the interwoven civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome known together as the Greco-Roman world, centered on the Mediterranean Basin. It is the period during which ancient Greece and ancient Rome flourished and had major influence throughout much of Europe, North Africa, and West Asia.

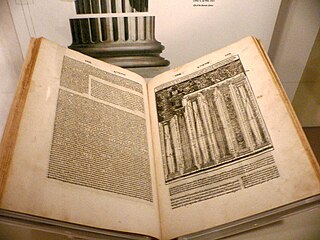

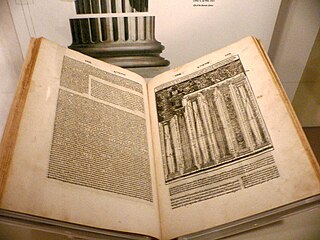

De architectura is a treatise on architecture written by the Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide for building projects. As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissance as the first known book on architectural theory, as well as a major source on the canon of classical architecture.

A cadastre or cadaster is a comprehensive recording of the real estate or real property's metes-and-bounds of a country. Often it is represented graphically in a cadastral map.

The Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum is a Roman book on land surveying which collects works by Siculus Flaccus, Frontinus, Agennius Urbicus, Hyginus Gromaticus and other writers, known as the Gromatici or Agrimensores. The work is preserved in various manuscripts, of which the oldest is the 6th or 7th-century Codex Arcerianus.

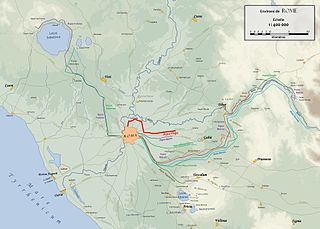

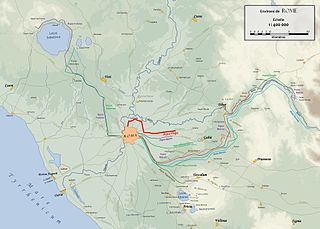

The Aqua Virgo was one of the eleven Roman aqueducts that supplied the city of ancient Rome. It was completed in 19 BC by Marcus Agrippa, during the reign of the emperor Augustus and was built mainly to supply the contemporaneous Baths of Agrippa in the Campus Martius.

The Romans constructed aqueducts throughout their Republic and later Empire, to bring water from outside sources into cities and towns. Aqueduct water supplied public baths, latrines, fountains, and private households; it also supported mining operations, milling, farms, and gardens.

Hyginus, usually distinguished as Hyginus Gromaticus, was a Latin writer on land-surveying, who flourished in the reign of Trajan. Fragments of a work on boundaries attributed to him are found in Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum, a collection of works on land surveying compiled in Late Antiquity.

Marcus Fulvius Flaccus was a Roman senator and an ally of the Gracchi. He served as consul in 125 BC and as plebeian tribune in 122 BC.

The groma was a surveying instrument used in the Roman Empire. The groma allowed projecting right angles and straight lines and thus enabling the centuriation. It is the only Roman surveying tool with examples that made it through to the present day.

A Roman colonia was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It is also the origin of the modern term "colony."

Siculus Flaccus was an ancient Roman gromaticus, and writer in Latin on land surveying. His work was included in a collection of gromatic treatises in the 6th century AD.

Aggenus Urbicus was an ancient Roman technical writer appearing in the Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum, a collection of works on land surveying from Late Antiquity. It is uncertain when he lived, but he may have been a Christian living in the later part of the 4th century, judging by expressions he uses.

Centuriation, also known as Roman grid, was a method of land measurement used by the Romans. In many cases land divisions based on the survey formed a field system, often referred to in modern times by the same name. According to O. A. W. Dilke, centuriation combined and developed features of land surveying present in Egypt, Etruria, Greek towns and Greek countryside.

Marcus Junius Nipsus was a second-century Roman gromatic writer, who also dealt with various mathematical questions. His surviving writings are preserved in the Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum, a compilation of Latin works on land surveying made in the 4th or 5th centuries AD.

In a typical Roman city, an umbilicus represented the reference point used by the city planners to map out the city spaces, including the pomerium, a sacred city boundary. The place for an umbilicus was supposedly set by examining the sky.