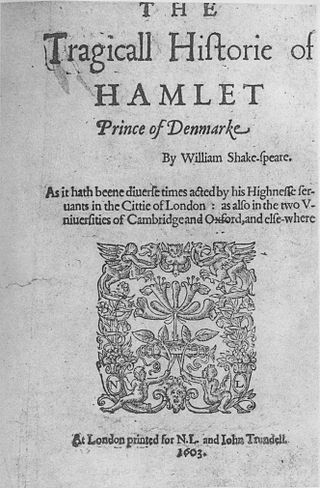

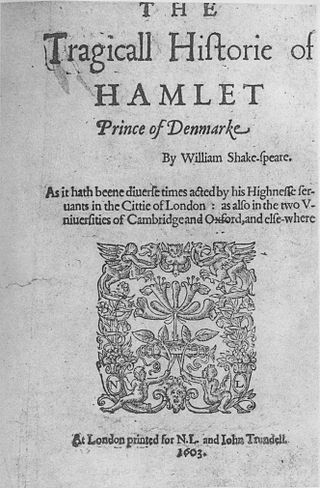

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, often shortened to Hamlet, is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play depicts Prince Hamlet and his attempts to exact revenge against his uncle, Claudius, who has murdered Hamlet's father in order to seize his throne and marry Hamlet's mother. Hamlet is considered among the "most powerful and influential tragedies in the English language", with a story capable of "seemingly endless retelling and adaptation by others". It is widely considered one of the greatest plays of all time. Three different early versions of the play are extant: the First Quarto ; the Second Quarto ; and the First Folio. Each version includes lines and passages missing from the others.

The earliest texts of William Shakespeare's works were published during the 16th and 17th centuries in quarto or folio format. Folios are large, tall volumes; quartos are smaller, roughly half the size. The publications of the latter are usually abbreviated to Q1, Q2, etc., where the letter stands for "quarto" and the number for the first, second, or third edition published.

Polonius is a character in William Shakespeare's play Hamlet. He is the chief counsellor of the play's ultimate villain, Claudius, and the father of Laertes and Ophelia. Generally regarded as wrong in every judgment he makes over the course of the play, Polonius is described by William Hazlitt as a "sincere" father, but also "a busy-body, [who] is accordingly officious, garrulous, and impertinent". In Act II, Hamlet refers to Polonius as a "tedious old fool" and taunts him as a latter day "Jephtha".

The Ur-Hamlet is a play by an unknown author, thought to be either Thomas Kyd or William Shakespeare. No copy of the play, dated by scholars to the second half of 1587, survives today. The play was staged in London, more specifically at The Theatre in Shoreditch as recalled by Elizabethan author Thomas Lodge. It includes a character named Hamlet; the only other known character from the play is a ghost who, according to Thomas Lodge in his 1596 publication Wits Misery and the Worlds Madnesse, cries "Hamlet, revenge!"

This article presents a possible chronological listing of the composition of the plays of William Shakespeare.

"To be, or not to be" is a speech given by Prince Hamlet in the so-called "nunnery scene" of William Shakespeare's play Hamlet. The speech is named for the opening phrase, itself among the most widely known and quoted lines in modern English literature, and has been referenced in many works of theatre, literature and music.

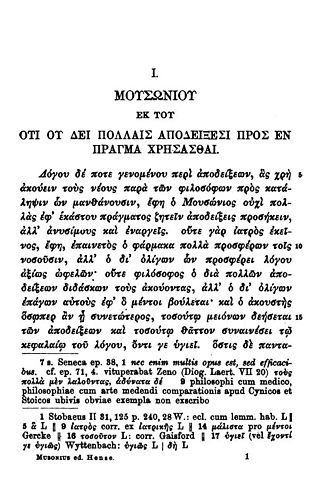

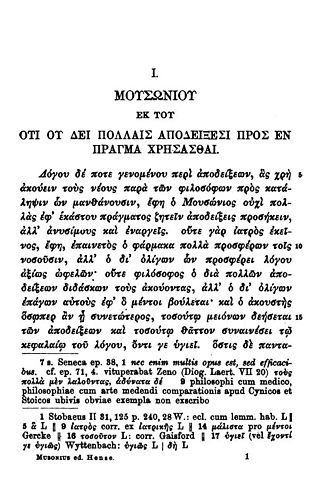

A critical apparatus in textual criticism of primary source material, is an organized system of notations to represent, in a single text, the complex history of that text in a concise form useful to diligent readers and scholars. The apparatus typically includes footnotes, standardized abbreviations for the source manuscripts, and symbols for denoting recurring problems.

A bad quarto, in Shakespearean scholarship, is a quarto-sized printed edition of one of Shakespeare's plays that is considered to be unauthorised, and is theorised to have been pirated from a theatrical performance without permission by someone in the audience writing it down as it was spoken or, alternatively, written down later from memory by an actor or group of actors in the cast – the latter process has been termed "memorial reconstruction". Since the quarto derives from a performance, hence lacks a direct link to the author's original manuscript, the text would be expected to be "bad", i.e. to contain corruptions, abridgements and paraphrasings.

The authority of a text is its reliability as a witness to the author's intentions. These intentions could be initial, medial or final, but intentionalist editors generally attempt to retrieve final authorial intentions. The concept is of particular importance for textual critics, whether they believe that authorial intention is recoverable, or whether they think that this recovery is impossible.

Valentine Simmes was an Elizabethan era and Jacobean era printer; he did business in London, "on Adling Hill near Bainard's Castle at the sign of the White Swan." Simmes has a reputation as one of the better printers of his generation, and was responsible for several quartos of Shakespeare's plays. [See: Early texts of Shakespeare's works.]

Thomas Creede was a printer of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, rated as "one of the best of his time." Based in London, he conducted his business under the sign of the Catherine Wheel in Thames Street from 1593 to 1600, and under the sign of the Eagle and Child in the Old Exchange from 1600 to 1617. Creede is best known for printing editions of works in English Renaissance drama, especially for ten editions of six Shakespearean plays and three works in the Shakespeare Apocrypha.

Cuthbert Burby was a London bookseller and publisher of the Elizabethan and early Jacobean eras. He is known for publishing a series of significant volumes of English Renaissance drama, including works by William Shakespeare, Robert Greene, John Lyly, and Thomas Nashe.

What follows is an overview of the main characters in William Shakespeare's Hamlet, followed by a list and summary of the minor characters from the play. Three different early versions of the play survive: known as the First Quarto ("Q1"), Second Quarto ("Q2"), and First Folio ("F1"), each has lines—and even scenes—missing in the others, and some character names vary.

Memorial reconstruction is the hypothesis that the scripts of some 17th century plays were written down from memory by actors who had played parts in them, and that those transcriptions were published. The theory is suggested as an explanation for the so-called "bad quarto" versions of plays, in which the texts differ dramatically from later published versions, or appear to be corrupted or confused.

William Shakespeare's Hamlet is a tragedy, believed to have been written between 1599 and 1601. It tells the story of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark—who takes revenge on the current king for killing the previous king and for marrying his father's widow —and it charts the course of his real or feigned madness. Hamlet is the longest play—and Hamlet is the largest part—in the entire Shakespeare canon. Critics say that Hamlet "offers the greatest exhibition of Shakespeare's powers".

Quarto is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produce eight book pages. Each printed page presents as one-fourth size of the full sheet.

"Hoist with his own petard" is a phrase from a speech in William Shakespeare's play Hamlet that has become proverbial. The phrase's meaning is that a bomb-maker is blown off the ground by his own bomb ("petard"), and indicates an ironic reversal or poetic justice.

Nicholas Ling (fl.1570–1607) was a London publisher, bookseller, and editor who published several important Elizabethan works, including the first and second quartos of Shakespeare's Hamlet.

Fratricide Punished, or The Tragedy of Fratricide Punished: or Prince Hamlet of Denmark, is the English name of a German-language play of anonymous origins and disputed age. Because of similarities of plot and dramatis personae, it is considered to be a German variant of the English play Hamlet, though possibly not William Shakespeare's Hamlet, and is a problematic figure in discussions of Hamlet Q1 and the so-called Ur-Hamlet. Such discussions have helped to raise interest in the text, which primarily lived in obscurity before the discovery of Q1 in 1823. Fratricide Punished was first published in German from a written manuscript in 1781 and translated to English by Georgina Archer in 1865. Though the play is readily available online both in English and in German, the manuscript has been lost since its initial publication, and all subsequent editions of the text are, as such, at a remove from the original. Fratricide Punished is often referred to by its German title Der Bestrafte Brudermord, or Tragoedia der bestrafte Bruder-mord oder: Prinz Hamlet aus Dännemark.