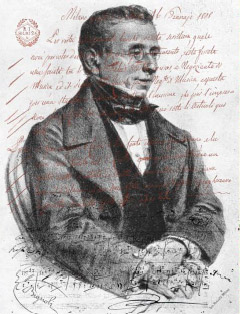

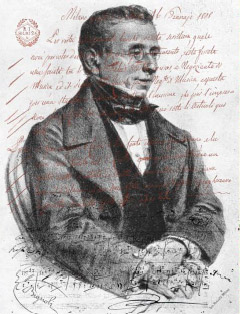

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto, a small town in the province of Parma, to a family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the help of a local patron, Antonio Barezzi. Verdi came to dominate the Italian opera scene after the era of Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, and Gaetano Donizetti, whose works significantly influenced him.

Falstaff is a comic opera in three acts by the Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi. The Italian-language libretto was adapted by Arrigo Boito from the play The Merry Wives of Windsor and scenes from Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2, by William Shakespeare. The work premiered on 9 February 1893 at La Scala, Milan.

La Scala is a historic opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as il Nuovo Regio Ducale Teatro alla Scala. The premiere performance was Antonio Salieri's Europa riconosciuta.

Otello is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on Shakespeare's play Othello. It was Verdi's penultimate opera, first performed at the Teatro alla Scala, Milan, on 5 February 1887.

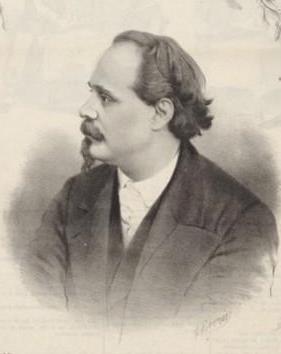

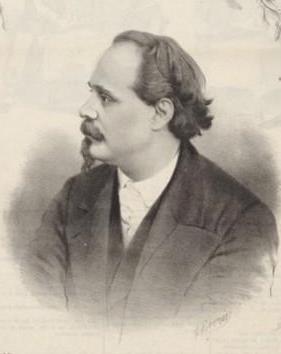

Arrigo Boito was an Italian librettist, composer, poet and critic whose only completed opera was Mefistofele. Among the operas for which he wrote the libretti are Giuseppe Verdi's monumental last two operas Otello and Falstaff as well as Amilcare Ponchielli's La Gioconda.

Mefistofele is an opera in a prologue and five acts, later reduced to four acts and an epilogue, the only completed opera with music by the Italian composer-librettist Arrigo Boito. The opera was given its premiere on 5 March 1868 at La Scala, Milan, under the baton of the composer, despite his lack of experience and skill as a conductor.

Casa Ricordi is a publisher of primarily classical music and opera. Its classical repertoire represents one of the important sources in the world through its publishing of the work of the major 19th-century Italian composers such as Gioachino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti, Vincenzo Bellini, Giuseppe Verdi, and, later in the century, Giacomo Puccini, composers with whom one or another of the Ricordi family came into close contact.

Francesco (Franco) Antonio Faccio was an Italian composer and conductor. Born in Verona, he studied music at the Milan Conservatory from 1855 where he was a pupil of Stefano Ronchetti-Monteviti and, as scholar William Ashbrook notes, "where he struck up a lifelong friendship with Arrigo Boito, two years his junior" and with whom he was to collaborate in many ways.

Scapigliatura is the name of an artistic movement that developed in Italy after the Risorgimento period (1815–71). The movement included poets, writers, musicians, painters and sculptors. The term Scapigliatura is the Italian equivalent of the French "bohème" (bohemian), and "Scapigliato" literally means "unkempt" or "dishevelled". Most of these authors have never been translated into English, hence in most cases this entry cannot have and has no detailed references to specific sources from English books and publications. However, a list of sources from Italian academic studies of the subject is included, as is a list of the authors' main works in Italian.

Nerone (Nero) is an opera in four acts composed by Arrigo Boito, to a libretto in Italian written by the composer. The work is a series of scenes from Imperial Rome at the time of Emperor Nero depicting tensions between the Imperial religion and Christianity, and ends with the Great Fire of Rome. Boito died in 1918 before finishing the work.

Nazzareno De Angelis was an Italian operatic bass, particularly associated with Verdi, Rossini and Wagner roles.

Romilda Pantaleoni was an Italian dramatic soprano who had a prolific opera career in Italy during the 1870s and 1880s. She sang a wide repertoire that encompassed bel canto roles, Italian and French grand opera, verismo operas, and the German operas of Richard Wagner. She became particularly associated with the roles of Margherita in Boito's Mefistofele and the title role in Ponchielli's La Gioconda; two roles which she performed in opera houses throughout Italy. She is best remembered today for originating the roles of Desdemona in Giuseppe Verdi's Otello (1887) and Tigrana in Giacomo Puccini's Edgar (1889). Universally admired for her acting skills as well as her singing abilities, Pantaleoni was compared by several critics to the great Italian stage actress Eleonora Duse.

Pasquale Bona was an Italian composer. He studied music at the Palermo Conservatory. He composed a number of operas, including one based on the Schiller play that would later inspire Giuseppe Verdi's Don Carlos. Bona later taught at the Conservatory in Milan, where he counted among his pupils Amilcare Ponchielli, Arrigo Boito, Franco Faccio and Alfredo Catalani; he was also friends with Alessandro Manzoni.

Gaetano Coronaro was an Italian conductor, pedagogue, and composer. He was born in Vicenza and had his initial musical training there followed by study from 1871 to 1873 at the Milan Conservatory under Franco Faccio. He composed orchestral works, sacred music, and chamber pieces as well as several works for the stage. La creola, which premiered at the Teatro Comunale di Bologna in 1878, was the only one to have any success.

Mario Tiberini was an Italian tenor who sang leading roles in the opera houses of Europe and the Americas in a career spanning 25 years. Known for his advanced singing technique and dramatic ability, he sang the role of Alvaro in the premiere of the revised version of Verdi's La forza del destino and created several roles in operas by lesser-known composers, including the title role in Faccio's Amleto.

Angiolina Ortolani-Tiberini was an Italian soprano who sang many leading roles in European opera houses during a career spanning over twenty years. After their marriage in 1858, her career was closely entwined with that of her husband, the tenor Mario Tiberini, with the couple often appearing together on stage. Amongst the roles she created was Ofelia in Franco Faccio's Amleto.

Opera Southwest is an American professional opera company based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Founded in 1972, it has presented many world premieres of new operas in addition to the standard repertoire. In 2015, its production of Franco Faccio's Amleto, the opera's first performance in 143 years, was a finalist in the International Opera Awards. Anthony Barrese, who joined the company in 2007 as Music Director, has been its Artistic Director and Principal Conductor since 2011. Its Director of Artistic Operations and Principal Stage Director is David Bartholomew.

Maria Tudor is an opera in four acts composed by Antônio Carlos Gomes to an Italian-language libretto by Emilio Praga. The libretto is based on Victor Hugo's 1833 play Marie Tudor, which centers on the rise, fall and execution of Fabiano Fabiani, a fictional favourite of Mary I of England. The opera premiered on 27 March 1879 at La Scala, Milan, with Anna D'Angeri in the title role and Francesco Tamagno as Fabiani. The opera was a failure at its premiere and withdrawn, a heavy blow to Gomes who was in serious financial and family difficulties at the time. He returned to his native Brazil the following year.

Iulia Maria Dan is a Romanian operatic soprano. She was a member of the ensemble of the Hamburg State Opera from 2015 to 2018, and then moved on to the Semperoper in Dresden. She appeared at international opera houses and festivals in leading roles such as Mozart's Fiordiligi and Massenet's Manon, but also in unusual repertoire including Ofelia in the revival of Franco Faccio's Amleto.

Pavel Černoch is a Czech operatic tenor.