Related Research Articles

Eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or promoting those judged to be superior. In recent years, the term has seen a revival in bioethical discussions on the usage of new technologies such as CRISPR and genetic screening, with heated debate around whether these technologies should be considered eugenics or not.

Sir Francis Galton was a British polymath and the originator of the behavioral genetics movement during the Victorian era.

The term racial hygiene was used to describe an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, which found its most extensive implementation in Nazi Germany. It was marked by efforts to avoid miscegenation, analogous to an animal breeder seeking purebred animals. This was often motivated by the belief in the existence of a racial hierarchy and the related fear that "lower races" would "contaminate" a "higher" one. As with most eugenicists at the time, racial hygienists believed that the lack of eugenics would lead to rapid social degeneration, the decline of civilization by the spread of inferior characteristics.

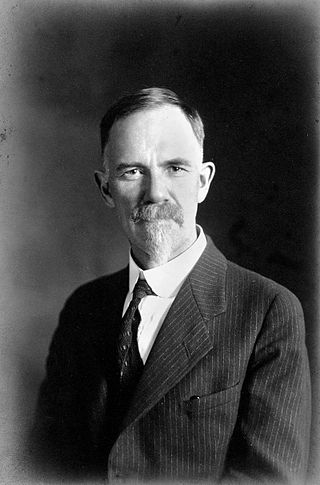

Madison Grant was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known for his work as a conservationist, eugenicist, and advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted for his far-reaching achievements in conservation than for his pseudoscientific advocacy of Nordicism, a form of racism which views the "Nordic race" as superior.

The term feeble-minded was used from the late 19th century in Europe, the United States and Australasia for disorders later referred to as illnesses or deficiencies of the mind.

The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness was a 1912 book by the American psychologist and eugenicist Henry H. Goddard, dedicated to his patron Samuel Simeon Fels. Supposedly an extended case study of Goddard’s for the inheritance of "feeble-mindedness", a general category referring to a variety of mental disabilities including intellectual disability, learning disabilities, and mental illness, the book is noted for factual inaccuracies that render its conclusions invalid. Goddard believed that a variety of mental traits were hereditary and that society should limit reproduction by people possessing these traits.

Paul Bowman Popenoe was an American marriage counselor, eugenicist and agricultural explorer. He was an influential advocate of the compulsory sterilization of mentally ill people and people with mental disabilities, and the father of marriage counseling in the United States.

The Eugenics Record Office (ERO), located in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, United States, was a research institute that gathered biological and social information about the American population, serving as a center for eugenics and human heredity research from 1910 to 1939. It was established by the Carnegie Institution of Washington's Station for Experimental Evolution, and subsequently administered by its Department of Genetics.

Harry Hamilton Laughlin was an American educator and eugenicist. He served as the superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office from its inception in 1910 to its closure in 1939, and was among the most active individuals influencing American eugenics policy, especially compulsory sterilization legislation.

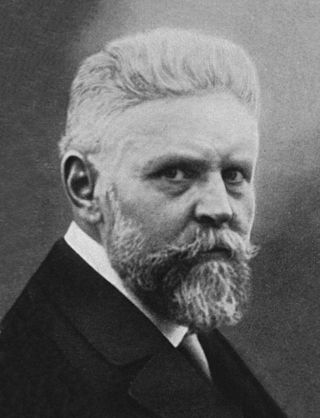

Charles Benedict Davenport was a biologist and eugenicist influential in the American eugenics movement.

The American Eugenics Society (AES) was a pro-eugenics organization dedicated to "furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of human populations". It endorsed the study and practice of Eugenics in the United States. Its original name as the American Eugenics Society lasted from 1922 to 1973, but the group changed their name after open use of the term "eugenics" became disfavored; it was known as the Society for the Study of Social Biology from 1973-2008, and the Society for Biodemography and Social Biology from 2008–2019. The Society was disbanded in 2019.

Daniel J. Kevles is an American historian of science best known for his books on American physics and eugenics and for a wide-ranging body of scholarship on science and technology in modern societies. He is Stanley Woodward Professor of History, Emeritus at Yale University and J. O. and Juliette Koepfli Professor of the Humanities, Emeritus at the California Institute of Technology.

The Jukes family was a New York "hill family" studied in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The studies are part of a series of other family studies, including the Kallikaks, the Zeros and the Nams, that were often quoted as arguments in support of eugenics, though the original Jukes study, by Richard L. Dugdale, placed considerable emphasis on the environment as a determining factor in criminality, disease and poverty (euthenics).

Three International Eugenics Congresses took place between 1912 and 1932 and were the global venue for scientists, politicians, and social leaders to plan and discuss the application of programs to improve human heredity in the early twentieth century.

Homo Sapiens 1900 is a 1998 Swedish documentary film directed by Peter Cohen, about various eugenics methods that were in practice in Europe during the first part of the 20th century.

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th century. The cause became increasingly promoted by intellectuals of the Progressive Era.

The history of eugenics is the study of development and advocacy of ideas related to eugenics around the world. Early eugenic ideas were discussed in Ancient Greece and Rome. The height of the modern eugenics movement came in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Gertrude Anna Davenport, was an American zoologist who worked as both a researcher and an instructor at established research centers such as the University of Kansas and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory where she studied embryology, development, and heredity. The wife of Charles Benedict Davenport, a prominent eugenicist, she co-authored several works with her husband. Together, they were highly influential in the United States eugenics movement during the progressive era.

Amy Barrington was an Irish teacher and scientist who was closely associated with the practices and beliefs of eugenics. She published several papers on that subject as well as indexing a work on history. She also wrote an account of the family history of the Barringtons. Amy Barrington herself states in 'The Barrington family history' that she occupied herself in learning and travelling for 26 years before deciding to pursue her family's ancestral history. She was the youngest daughter of Edward Barrington of Fassaroe, Bray, County Wicklow, Ireland.

Alfred Milne Gossage, was a British physician and dean of Westminster Hospital. He was an author in Garrod, Batten and Thursfield's Diseases of Children and Latham and English's System of Treatment. In 1908, he coined the term woolly hair after observing it in 18 members in three generations of a European family. He received the CBE in 1920.

References

- ↑ Charles Benedict Davenport . Retrieved 2018-07-03.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Charles Davenport's Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Controlling Heredity

- ↑ Vidnes, Thea (October 2009). "Jan A Witkowski and John R Inglis (eds), Davenport's dream: 21st century reflections on heredity and eugenics, New York, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2008, pp. xiii, 298, $55.00 (hardback 978-0-87969-756-3)". Medical History. 53 (4): 609–610. doi: 10.1017/S0025727300000727 . ISSN 2048-8343.