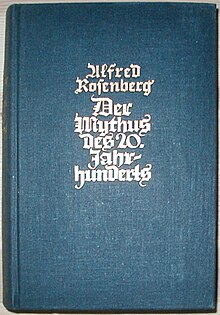

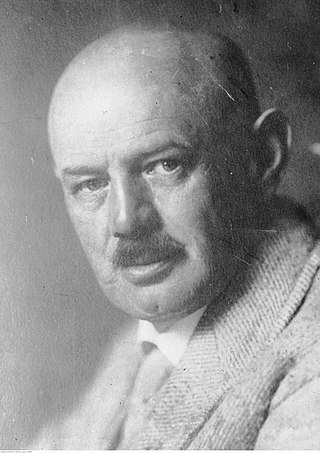

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of the NSDAP Office of Foreign Affairs during the entire rule of Nazi Germany (1933–1945), and led Amt Rosenberg, an official Nazi body for cultural policy and surveillance, between 1934 and 1945. During World War II, Rosenberg was the head of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (1941–1945). After the war, he was convicted of crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes; and crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg trials in 1946. He was sentenced to death by hanging and executed on 16 October 1946.

Dietrich Eckart was a German völkisch poet, playwright, journalist, publicist, and political activist who was one of the founders of the German Workers' Party, the precursor of the Nazi Party. Eckart was a key influence on Adolf Hitler in the early years of the Party, the original publisher of the party newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, and the lyricist of the first party anthem, "Sturmlied". He was a participant in the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923 and died on 26 December of that year, shortly after his release from Landsberg Prison, of a heart attack.

German Christians were a pressure group and a movement within the German Evangelical Church that existed between 1932 and 1945, aligned towards the antisemitic, racist, and Führerprinzip ideological principles of Nazism with the goal to align German Protestantism as a whole towards those principles. Their advocacy of these principles led to a schism within 23 of the initially 28 regional church bodies (Landeskirchen) in Germany and the attendant foundation of the opposing Confessing Church in 1934. Siegfried Leffler was a co-founder of the German Christians.

Untermensch is a German language word literally meaning 'underman', 'sub-man', or 'subhuman', that was extensively used by Germany's Nazi Party to refer to non-Aryan people they deemed as inferior. It was mainly used against "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs.

Nazi Germany was an overwhelmingly Christian nation. A census in May 1939, six years into the Nazi era after the annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia into Germany, indicates that 54% of the population considered itself Protestant, 41% considered itself Catholic, 3.5% self-identified as Gottgläubig, and 1.5% as "atheist". Protestants were over-represented in the Nazi Party's membership and electorate, and Catholics were under-represented.

Positive Christianity was a religious movement within Nazi Germany which promoted the belief that the racial purity of the German people should be maintained by mixing racialistic Nazi ideology with either fundamental or significant elements of Nicene Christianity. Adolf Hitler used the term in point 24 of the 1920 Nazi Party Platform, stating: "the Party as such represents the viewpoint of Positive Christianity without binding itself to any particular denomination". The Nazi movement had been hostile to Germany's established churches. The new Nazi idea of Positive Christianity allayed the fears of Germany's Christian majority by implying that the Nazi movement was not anti-Christian. That said, in 1937, Hans Kerrl, the Reich Minister for Church Affairs, explained that "Positive Christianity" was not "dependent upon the Apostle's Creed", nor was it dependent on "faith in Christ as the son of God", upon which Christianity relied; rather, it was represented by the Nazi Party: "The Führer is the herald of a new revelation", he said.

The religious beliefs of Adolf Hitler, dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, have been a matter of debate. His opinions regarding religious matters changed considerably over time. During the beginning of his political career, Hitler publicly expressed favorable opinions towards traditional Christian ideals, but later abandoned them. Most historians describe his later posture as adversarial to organized Christianity and established Christian denominations. He also criticized atheism.

In Nazi Germany, Gottgläubig was a Nazi religious term for a form of non-denominationalism and deism practised by those German citizens who had officially left Christian churches but professed faith in some higher power or divine creator. Such people were called Gottgläubige, and the term for the overall movement was Gottgläubigkeit ; the term denotes someone who still believes in a God, although without having any institutional religious affiliation. These Nazis were not favourable towards religious institutions of their time, nor did they tolerate atheism of any type within their ranks. The 1943 Philosophical Dictionary defined Gottgläubig as: "official designation for those who profess a specific kind of piety and morality, without being bound to a church denomination, whilst however also rejecting irreligion and godlessness." The Gottgläubigkeit was a form of deism, and was "predominantly based on creationist and deistic views". In the 1939 census, 3.5% of the German population identified as Gottgläubig.

"Hitler's Table Talk" is the title given to a series of World War II monologues delivered by Adolf Hitler, which were transcribed from 1941 to 1944. Hitler's remarks were recorded by Heinrich Heim, Henry Picker, Hans Müller and Martin Bormann and later published by different editors under different titles in four languages.

Kirchenkampf is a German term which pertains to the situation of the Christian churches in Germany during the Nazi period (1933–1945). Sometimes used ambiguously, the term may refer to one or more of the following different "church struggles":

- The internal dispute within German Protestantism between the German Christians and the Confessing Church over control of the Protestant churches;

- The tensions between the Nazi regime and the Protestant church bodies; and

- The tensions between the Nazi regime and the Catholic Church.

Martin Luther (1483–1546) was a German professor of theology, priest and seminal leader of the Reformation. His positions on Judaism continue to be controversial. These changed dramatically from his early career, where he showed concern for the plight of European Jews, to his later years, when embittered by his failure to convert them to Christianity, he became outspokenly antisemitic in his statements and writings.

Historians, political scientists and philosophers have studied Nazism with a specific focus on its religious and pseudo-religious aspects. It has been debated whether Nazism would constitute a political religion, and there has also been research on the millenarian, messianic, and occult or esoteric aspects of Nazism.

Richard Steigmann-Gall is an Associate Professor of History at Kent State University, and the former Director of the Jewish Studies Program from 2004 to 2010.

The propaganda of the Nazi regime that governed Germany from 1933 to 1945 promoted Nazi ideology by demonizing the enemies of the Nazi Party, notably Jews and communists, but also capitalists and intellectuals. It promoted the values asserted by the Nazis, including Heldentod, Führerprinzip, Volksgemeinschaft, Blut und Boden and pride in the Germanic Herrenvolk. Propaganda was also used to maintain the cult of personality around Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, and to promote campaigns for eugenics and the annexation of German-speaking areas. After the outbreak of World War II, Nazi propaganda vilified Germany's enemies, notably the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and the United States, and in 1943 exhorted the population to total war.

Nazism, formally National Socialism, is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power in 1930s Europe, it was frequently referred to as Hitler Fascism and Hitlerism. The later related term "neo-Nazism" is applied to other far-right groups with similar ideas which formed after the Second World War when the Third Reich collapsed.

Music in Nazi Germany, like all cultural activities in the regime, was controlled and "co-ordinated" (Gleichschaltung) by various entities of the state and the Nazi Party, with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and the prominent Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg playing leading – and competing – roles. The primary concerns of these organizations was to exclude Jewish composers and musicians from publishing and performing music, and to prevent the public exhibition of music considered to be "Jewish", "anti-German", or otherwise "degenerate", while at the same time promoting the work of favored "Germanic" composers, such as Richard Wagner and Anton Bruckner. These works were believed to be positive contributions to the Volksgemeinschaft, or German folk community.

Nazi ideology could not accept an autonomous establishment whose legitimacy did not spring from the government. It desired the subordination of the church to the state. To many Nazis, Catholics were suspected of insufficient patriotism, or even of disloyalty to the Fatherland, and of serving the interests of "sinister alien forces". Nazi radicals also disdained the Semitic origins of Jesus and the Christian religion. Although the broader membership of the Nazi Party after 1933 came to include many Catholics, aggressive anti-church radicals like Alfred Rosenberg, Martin Bormann, and Heinrich Himmler saw the kirchenkampf campaign against the churches as a priority concern, and anti-church and anti-clerical sentiments were strong among grassroots party activists.

The Roman Catholic Church suffered persecution in Nazi Germany. The Nazis claimed jurisdiction over all collective and social activity. Clergy were watched closely, and frequently denounced, arrested and sent to Nazi concentration camps. Welfare institutions were interfered with or transferred to state control. Catholic schools, press, trade unions, political parties and youth leagues were eradicated. Anti-Catholic propaganda and "morality" trials were staged. Monasteries and convents were targeted for expropriation. Prominent Catholic lay leaders were murdered, and thousands of Catholic activists were arrested.

The German Reformation theologian Martin Luther was widely lauded in Nazi Germany prior to the Nazi government's dissolution in 1945, with German leadership praising his seminal position in German history while leveraging his antisemitism and folk hero status to further legitimize their own positive Christian religious policies and Germanic ethnonationalism. Luther was seen as both a cross-confessional figurehead and as a symbol of German Protestant support for the Nazi regime in particular, with a religious leader even comparing Führer Adolf Hitler to Luther directly.