Related Research Articles

Eric Arthur Blair was an English novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitarianism, and support of democratic socialism.

René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laennec was a French physician and musician. His skill at carving his own wooden flutes led him to invent the stethoscope in 1816, while working at the Hôpital Necker. He pioneered its use in diagnosing various chest conditions. He became a lecturer at the Collège de France in 1822 and professor of medicine in 1823. His final appointments were that of head of the medical clinic at the Hôpital de la Charité and professor at the Collège de France. He went into a coma and subsequently died of tuberculosis on August 13, 1826 at age 45.

Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Louis was a French physician, clinician and pathologist known for his studies on tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and pneumonia, but Louis's greatest contribution to medicine was the development of the "numerical method", forerunner to epidemiology and the modern clinical trial, paving the path for evidence-based medicine.

Jean Guillaume Auguste Lugol was a French physician.

Partners In Health (PIH) is an international nonprofit public health organization founded in 1987 by Paul Farmer, Ophelia Dahl, Thomas J. White, Todd McCormack, and Jim Yong Kim.

Hillingdon Hospital is an hospital in Hillingdon, London. It is one of two hospitals run by The Hillingdon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, the other being Mount Vernon Hospital.

National Jewish Health is a Denver, Colorado academic hospital/clinic doing research and treatment in respiratory, cardiac, immune and related disorders. It is an internationally respected medical center that draws people from many countries to receive care. Founded in 1899 to treat tuberculosis, it is non-sectarian but had funding from B'nai B'rith until the 1950s.

The Hôtel-Dieu is a public hospital located on the Île de la Cité in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, on the parvis of Notre-Dame. Tradition has it that the hospital was founded by Saint Landry in 651 AD, but the first official records date it to 829, making it the oldest in France and possibly the oldest continuously operating hospital in the world. The Hôtel-Dieu was the only hospital in the city until the beginning of the 17th century.

University Hospital Hairmyres is a district general hospital in the Hairmyres neighbourhood of East Kilbride, South Lanarkshire, Scotland. The hospital serves one of the largest elderly populations in Scotland. It is managed by NHS Lanarkshire.

A cottage hospital is a mostly obsolete type of small hospital, most commonly found in the United Kingdom.

The American Hospital of Paris, founded in 1906, is a private, not-for-profit, community hospital certified under the French healthcare system. Located in Neuilly-sur-Seine, in the western suburbs of Paris, France, it has 187 surgical, medical, and obstetric beds.

The Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital is a French teaching hospital in the 15th arrondissement of Paris. It is a hospital of the Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris group and is affiliated to the Université Paris Cité. Necker–Enfants Malades Hospital was created in 1920 by the merger of Necker Hospital, which was founded in 1778 by Suzanne Necker, with the physically contiguous Sick Children's Hospital, the oldest children's hospital in the Western world, founded in 1801.

Jean-Denis Cochin was a French Roman Catholic priest, preacher and philanthropist. In 1780, he founded Paris's Hôpital Cochin, as the hospice of Saint-Jacques du Haut Pas, in the rue du Faubourg Saint-Jacques.

The Hôpital Cochin is a hospital of public assistance in the rue du Faubourg-Saint-Jacques Paris 14e. It houses the central burn treatment centre of the city. The Hôpital Cochin is a section of the Faculté de Médecine Paris-Cité. It commemorates Jean-Denis Cochin, curé of the parish of Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas and founder of a hospital for the workers and poor of that quarter of Paris.

Barnhill is a farmhouse in the north of the island of Jura in the Scottish Inner Hebrides overlooking the Sound of Jura. It stands on the site of a larger 15th-century settlement, Cnoc an t-Sabhail; the English name Barnhill has been in use since the early twentieth century. The house was rented by the essayist and novelist George Orwell, who lived there intermittently from 1946 until January 1949. He completed his final novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, at Barnhill.

Léon Clément Le Fort was a French surgeon remembered for his work on uterine prolapse, including Le Fort's operation. He also described Le Fort's fracture of the ankle and Le Fort's amputation of the foot.

The history of medicine in France focuses on how the medical profession and medical institutions in France have changed over time. Early medicine in France was defined by, and administered by, the Catholic church. Medicine and care were one of the many charitable ventures of the church. During the era of the French Revolution, new ideas took hold within the world of medicine and medicine was made more scientific and the hospitals were made more medical. Paris Medicine is a term defining the series of changes to the hospital and care received with a hospital that occurred during the period of the French Revolution. Ideas from the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution were introduced into the medical field.

Gwen Grant Mellon was an American medical missionary and the founder and administrator of Hôpital Albert Schweitzer Haiti in Deschapelles, Haiti. As a single mother she worked as a riding instructor on a dude ranch in Arizona, where she met neighboring rancher William Larimer Mellon Jr., heir to the Mellon fortune. Shortly after their marriage in 1946, the couple decided to emulate the work of Dr. Albert Schweitzer in an underdeveloped country and enrolled at Tulane University, he to receive his medical degree and she to study tropical medicine. She planned the building of the 75-bed hospital in Haiti, paid for from the couple's personal fortune, and worked there from its opening in 1956 until her death. She was honored with the first Elizabeth Blackwell Award in 1958 and the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism in 2000.

Whiteabbey Hospital is a hospital located close to the village of Whiteabbey, within the town of Newtownabbey, Northern Ireland. The hospital first opened in 1907 as The Abbey Sanitorium, centred around a country house known as 'The Abbey'. The house has stood on the site from 1850, and was once the residence of prominent architect Charles Lanyon. The hospital was extended and several buildings added throughout the early 20th century, and it was renamed Whiteabbey Hospital in 1947. The hospital is managed by the Northern Health and Social Care Trust. Many healthcare services have been withdrawn from the hospital, most recently with the closure of the Minor Injuries Unit in 2014.

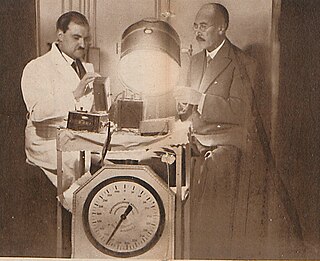

Jean Saidman was a French radiologist who promoted the idea of heliotherapy or actinotherapy, using solar radiation to cure various diseases such as tuberculosis. He built special rotating structures called solariums at Aix-les-Bains and Vallauris in France and at Jamnagar in India. After World War II he was also among the first to introduce Ayurvedic medicine and to encourage research on them in France.