Related Research Articles

Eric Arthur Blair was a British novelist, poet, essayist, journalist, and critic who wrote under the pen name of George Orwell, a name inspired by his favourite place River Orwell. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to all totalitarianism, and support of democratic socialism.

Wystan Hugh Auden was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, form, and content. Some of his best known poems are about love, such as "Funeral Blues"; on political and social themes, such as "September 1, 1939" and "The Shield of Achilles"; on cultural and psychological themes, such as The Age of Anxiety; and on religious themes, such as "For the Time Being" and "Horae Canonicae".

Down and Out in Paris and London is the first full-length work by the English author George Orwell, published in 1933. It is a memoir in two parts on the theme of poverty in the two cities. Its target audience was the middle- and upper-class members of society—those who were more likely to be well educated—and it exposes the poverty existing in two prosperous cities: Paris and London. The first part is an account of living in near-extreme poverty and destitution in Paris and the experience of casual labour in restaurant kitchens. The second part is a travelogue of life on the road in and around London from the tramp's perspective, with descriptions of the types of hostel accommodation available and some of the characters to be found living on the margins.

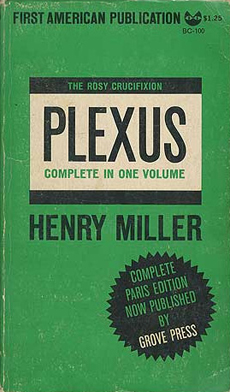

Henry Valentine Miller was an American novelist, short story writer and essayist. He broke with existing literary forms and developed a new type of semi-autobiographical novel that blended character study, social criticism, philosophical reflection, stream of consciousness, explicit language, sex, surrealist free association, and mysticism. His most characteristic works of this kind are Tropic of Cancer, Black Spring, Tropic of Capricorn, and the trilogy The Rosy Crucifixion, which are based on his experiences in New York City and Paris. He also wrote travel memoirs and literary criticism, and painted watercolors.

Coming Up for Air is the seventh book and fourth novel by English writer George Orwell, published in June 1939 by Victor Gollancz. It was written between 1938 and 1939 while Orwell spent time recuperating from illness in French Morocco, mainly in Marrakesh. He delivered the completed manuscript to Victor Gollancz upon his return to London in March 1939.

Christopher William Bradshaw Isherwood was an Anglo-American novelist, playwright, screenwriter, autobiographer, and diarist. His best-known works include Goodbye to Berlin (1939), a semi-autobiographical novel which inspired the musical Cabaret (1966); A Single Man (1964), adapted as a film by Tom Ford in 2009; and Christopher and His Kind (1976), a memoir which "carried him into the heart of the Gay Liberation movement".

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1936.

Rudolf John Frederick Lehmann was an English publisher, poet and man of letters. He founded the periodicals New Writing and The London Magazine, and the publishing house of John Lehmann Limited.

Tropic of Cancer is an autobiographical novel by Henry Miller that is best known as "notorious for its candid sexuality", with the resulting social controversy considered responsible for the "free speech that we now take for granted in literature." It was first published in 1934 by the Obelisk Press in Paris, France, but this edition was banned in the United States. Its publication in 1961 in the United States by Grove Press led to obscenity trials that tested American laws on pornography in the early 1960s. In 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the book non-obscene. It is regarded as an important work of 20th-century literature.

Naomi Mary Margaret Mitchison, Baroness Mitchison was a Scottish novelist and poet. Often called a doyenne of Scottish literature, she wrote more than 90 books of historical and science fiction, travel writing and autobiography. Her husband Dick Mitchison's life peerage in 1964 entitled her to call herself Lady Mitchison, but she never did. Her 1931 work, The Corn King and the Spring Queen, is seen by some as the prime 20th-century historical novel.

Tropic of Capricorn is a semi-autobiographical novel by Henry Miller, first published by Obelisk Press in Paris in 1939. A prequel of sorts to Miller's first published novel, 1934's Tropic of Cancer, it was banned in the United States until a 1961 Justice Department ruling declared that its contents were not obscene.

Goodbye to Berlin is a 1939 novel by Anglo-American writer Christopher Isherwood set during the waning days of the Weimar Republic. The novel recounts Isherwood's 1929–1932 sojourn as a pleasure-seeking British expatriate on the eve of Adolf Hitler's ascension as Chancellor of Germany and consists of a "series of sketches of disintegrating Berlin, its slums and nightclubs and comfortable villas, its odd maladapted types and its complacent burghers." The plot was based on factual events in Isherwood's life, and the novel's characters were based upon actual persons. The insouciant flapper Sally Bowles was based on teenage cabaret singer Jean Ross who became Isherwood's friend during his sojourn.

The Rosy Crucifixion, a trilogy consisting of Sexus, Plexus, and Nexus, is a fictionalized account documenting the six-year period of Henry Miller's life in Brooklyn as he falls for his second wife June and struggles to become a writer, leading up to his initial departure for Paris in 1928. The title comes from a sentence near the end of Miller's Tropic of Capricorn: "All my Calvaries were rosy crucifixions, pseudo-tragedies to keep the fires of hell burning brightly for the real sinners who are in danger of being forgotten."

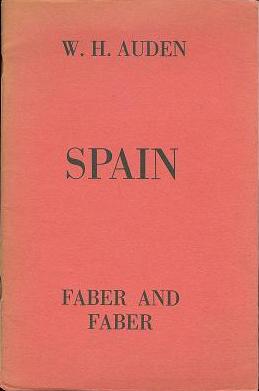

Spain is a poem by W. H. Auden written after his visit to the Spanish Civil War. Spain was described by George Orwell as "one of the few decent things that have been written about the Spanish war". It was written and published in 1937. Auden donated all the profits from the sale of Spain to the Spanish Medical Aid Committee.

Sir Stephen Harold Spender was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed U.S. Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1965.

"Poetry and the Microphone" is an essay by English writer George Orwell. It refers to his work at the BBC’s Eastern Service broadcasting half-hour-long literary programmes to India in the format of an imaginary monthly literary magazine. Written in 1943, it was not published until 1945, in New Saxon Pamphlet. Orwell had by then left the BBC.

The bibliography of George Orwell includes journalism, essays, novels, and non-fiction books written by the British writer Eric Blair (1903–1950), either under his own name or, more usually, under his pen name George Orwell. Orwell was a prolific writer on topics related to contemporary English society and literary criticism, who has been declared "perhaps the 20th century's best chronicler of English culture." His non-fiction cultural and political criticism constitutes the majority of his work, but Orwell also wrote in several genres of fictional literature.

Inside the Whale and Other Essays is a book of essays written by George Orwell in 1940. It includes the eponymous essay "Inside the Whale".

Jean Iris Ross Cockburn was a British journalist, political activist, and film critic. During the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), she was a war correspondent for the Daily Express and is alleged to have been a press agent for Joseph Stalin's Comintern. A skilled writer, Ross worked as a film critic for the Daily Worker. Throughout her life, she wrote political criticism, anti-fascist polemics, and socialist manifestos for a number of disparate organisations such as the British Workers' Film and Photo League. She was a devout Stalinist and a lifelong member of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

New Writing was a popular literary periodical in book format founded in 1936 by John Lehmann and committed to anti-fascism.

References

- ↑ Henry Miller Tropic of Cancer Obelisk Press 1934

- ↑ Alfred Perles My Friend Henry Miller Neville Spearman 1955

- ↑ Andy Croft, Red Letter Days : British fiction in the 1930s. London : Lawrence & Wishart, 1990. ISBN 0853157294 (pp. 17–29)

- 1 2 3 4 Janet Montefiore, Men and women writers of the 1930s : the dangerous flood of history. London : Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0415068924 (pp.13–18).