The Passion is the short final period before the death of Jesus, described in the four canonical gospels. It is commemorated in Christianity every year during Holy Week.

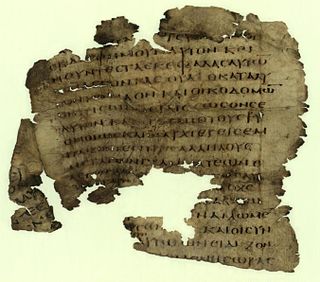

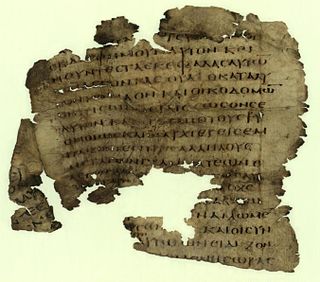

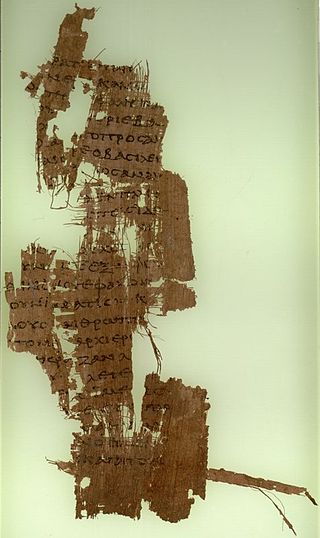

The Gospel of Nicodemus, also known as the Acts of Pilate, is an apocryphal gospel claimed to have been derived from an original Hebrew work written by Nicodemus, who appears in the Gospel of John as an associate of Jesus. The title "Gospel of Nicodemus" is medieval in origin. The dates of its accreted sections are uncertain, but the work in its existing form is thought to date to around the 4th or 5th century AD.

Herod Antipas was a 1st-century ruler of Galilee and Perea. He bore the title of tetrarch and is referred to as both "Herod the Tetrarch" and "King Herod" in the New Testament. He was a son of Herod the Great and a grandson of Antipater the Idumaean. He is widely known today for accounts in the New Testament of his role in events that led to the executions of John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth. His father, Herod the Great, was described in the account as ordering the Massacre of the Innocents, marking the earliest Biblical account of the concerns of the government in Jerusalem regarding Jesus' existence.

Two names and a variety of titles are used to refer to Jesus in the New Testament. In Christianity, the two names Jesus and Emmanuel that refer to Jesus in the New Testament have salvific attributes. After the crucifixion of Jesus the early Church did not simply repeat his messages, but focused on him, proclaimed him, and tried to understand and explain his message. One element of the process of understanding and proclaiming Jesus was the attribution of titles to him. Some of the titles that were gradually used in the early Church and then appeared in the New Testament were adopted from the Jewish context of the age, while others were selected to refer to, and underscore the message, mission and teachings of Jesus. In time, some of these titles gathered significant Christological significance.

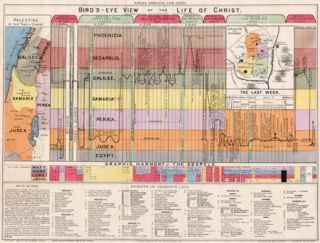

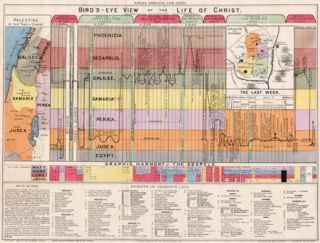

A chronology of Jesus aims to establish a timeline for the events of the life of Jesus. Scholars have correlated Jewish and Greco-Roman documents and astronomical calendars with the New Testament accounts to estimate dates for the major events in Jesus's life.

Jesus, also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the central figure of Christianity, the world's largest religion. Most Christian denominations believe Jesus to be the incarnation of God the Son and the awaited messiah, or Christ, a descendant from the Davidic line that is prophesied in the Old Testament. Virtually all modern scholars of antiquity agree that Jesus existed historically. Accounts of Jesus's life are contained in the Gospels, especially the four canonical Gospels in the New Testament. Academic research has yielded various views on the historical reliability of the Gospels and how closely they reflect the historical Jesus.

The life of Jesus is primarily outlined in the four canonical gospels, which includes his genealogy and nativity, public ministry, passion, prophecy, resurrection and ascension. Other parts of the New Testament – such as the Pauline epistles which were likely written within 20 to 30 years of each other, and which include references to key episodes in the life of Jesus, such as the Last Supper, and the Acts of the Apostles, which includes more references to the Ascension episode than the canonical gospels also expound upon the life of Jesus. In addition to these biblical texts, there are extra-biblical texts that make reference to certain events in the life of Jesus, such as Josephus on Jesus and Tacitus on Christ.

There exists a consensus among scholars that Jesus of Nazareth spoke the Aramaic language. Aramaic was the common language of Roman Judaea, and was thus also spoken by Jesus' disciples. The villages of Nazareth and Capernaum in Galilee, where he spent most of his time, were populated by Aramaic-speaking communities. Jesus probably spoke the Galilean dialect, distinguishable from that which was spoken in Roman-era Jerusalem. Based on the symbolic renaming or nicknaming of some of his apostles, it is also likely that Jesus or at least one of his apostles knew enough Koine Greek to converse with non-Judaeans. It is reasonable to assume that Jesus was well versed in Hebrew for religious purposes, as it is the liturgical language of Judaism.

Matthew 2:2 is the second verse of the second chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament. The magi travelling from the east have arrived at the court of King Herod in Jerusalem and in this verse inform him of their purpose.

Matthew 2:3 is the third verse of the second chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament. In the previous verse the magi had informed King Herod that they had seen portents showing the birth of the King of the Jews. In this verse he reacts to this news.

Matthew 2 is the second chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament. It describes the events after the birth of Jesus, the visit of the magi and the attempt by King Herod to kill the infant messiah, Joseph and his family's flight into Egypt, and their later return to live in Israel, settling in Nazareth.

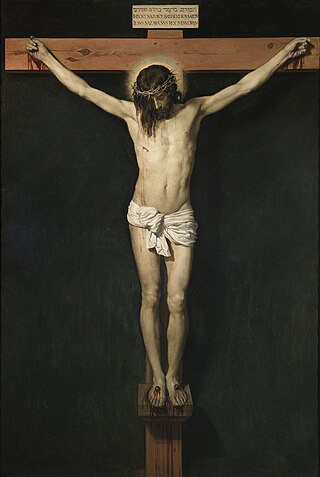

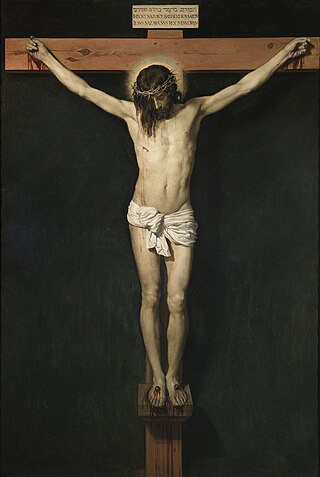

Mark 15 is the fifteenth chapter of the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. This chapter records the narrative of Jesus' passion, including his trial before Pontius Pilate and then his crucifixion, death and entombment. Jesus' trial before Pilate and his crucifixion, death, and burial are also recorded in Matthew 27, Luke 23, and John 18:28–19:42.

John 19 is the nineteenth chapter of the Gospel of John in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The book containing this chapter is anonymous, but early Christian tradition uniformly affirmed that John composed this Gospel. This chapter records the events on the day of the crucifixion of Jesus, until his burial.

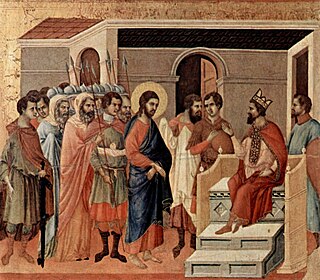

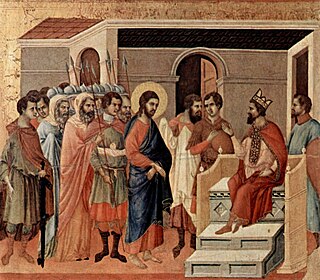

Luke 23 is the twenty-third chapter of the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The book containing this chapter is anonymous, but early Christian tradition uniformly affirmed that Luke the Evangelist composed this Gospel as well as the Acts of the Apostles. This chapter records the trial of Jesus Christ before Pontius Pilate, Jesus' meeting with Herod Antipas, and his crucifixion, death and burial.

Matthew 27:11 is the eleventh verse of the twenty-seventh chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament. This verse brings the narrative back to Pilate's Court, and the final trial of Jesus.

The crucifixion of Jesus was the death of Jesus by being nailed to a cross. It occurred in 1st-century Judaea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, and later attested to by other ancient sources. Scholars nearly universally accept the historicity of Jesus's crucifixion, although there is no consensus on the details.

In the canonical gospels, Pilate's court refers to the trial of Jesus in praetorium before Pontius Pilate, preceded by the Sanhedrin Trial. In the Gospel of Luke, Pilate finds that Jesus, being from Galilee, belonged to Herod Antipas' jurisdiction, and so he decides to send Jesus to Herod. After questioning Jesus and receiving very few replies, Herod sees Jesus as no threat and returns him to Pilate.

Jesus at Herod's court refers to an episode in the New Testament which describes Jesus being sent to Herod Antipas in Jerusalem, prior to his crucifixion. This episode is described in Luke 23.

Quod scripsi, scripsi is a Latin phrase. It was most famously used by Pontius Pilate in the Bible in response to the Jewish priests who objected to his writing "King of the Jews" on the sign (titulus) that was hung above Jesus at his Crucifixion. It is mostly found in the Latin Vulgate Bible.

Passion Gospels are early Christian texts that either mostly or exclusively relate to the last events of Jesus' life: the Passion of Jesus. They are generally classed as New Testament apocrypha. The last chapters of the four canonical gospels include Passion narratives, but later Christians hungered for more details. Just as infancy gospels expanded the stories of young Jesus, Passion Gospels expanded the story of Jesus's arrest, trial, execution, resurrection, and the aftermath. These documents usually claimed to be written by a participant mentioned in the gospels, with Nicodemus, Pontius Pilate, and Joseph of Arimathea as popular choices for author. These documents are considered more legendary than historical, however, and were not included in the eventual Canon of the New Testament.