Singapore maintains diplomatic relations with 189 UN member states. The three exceptions are the Central African Republic, Monaco and South Sudan.

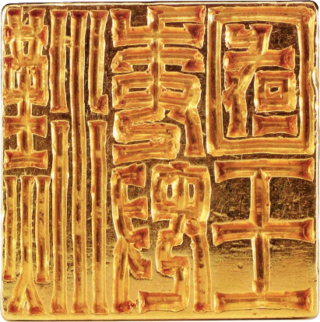

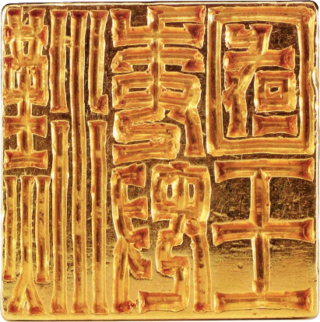

The Ryukyu Kingdom was a kingdom in the Ryukyu Islands from 1429 to 1879. It was ruled as a tributary state of imperial Ming China by the Ryukyuan monarchy, who unified Okinawa Island to end the Sanzan period, and extended the kingdom to the Amami Islands and Sakishima Islands. The Ryukyu Kingdom played a central role in the maritime trade networks of medieval East Asia and Southeast Asia despite its small size. The Ryukyu Kingdom became a vassal state of the Satsuma Domain of Japan after the invasion of Ryukyu in 1609 but retained de jure independence until it was transformed into the Ryukyu Domain by the Empire of Japan in 1872. The Ryukyu Kingdom was formally annexed and dissolved by Japan in 1879 to form Okinawa Prefecture, and the Ryukyuan monarchy was integrated into the new Japanese nobility.

Sakoku is the most common name for the isolationist foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, during the Edo period, relations and trade between Japan and other countries were severely limited, and almost all foreign nationals were banned from entering Japan, while common Japanese people were kept from leaving the country. The policy was enacted by the shogunate government (bakufu) under Tokugawa Iemitsu through a number of edicts and policies from 1633 to 1639. The term sakoku originates from the manuscript work Sakoku-ron (鎖國論) written by Japanese astronomer and translator Shizuki Tadao in 1801. Shizuki invented the word while translating the works of the 17th-century German traveller Engelbert Kaempfer namely, his book, 'the history of Japan', posthumously released in 1727.

John King Fairbank was an American historian of China and United States–China relations. He taught at Harvard University from 1936 until his retirement in 1977. He is credited with building the field of China studies in the United States after World War II with his organizational ability, his mentorship of students, support of fellow scholars, and formulation of basic concepts to be tested.

International relations between Japan and the United States began in the late 18th and early 19th century with the diplomatic but force-backed missions of U.S. ship captains James Glynn and Matthew C. Perry to the Tokugawa shogunate. Following the Meiji Restoration, the countries maintained relatively cordial relations. Potential disputes were resolved. Japan acknowledged American control of Hawaii and the Philippines, and the United States reciprocated regarding Korea. Disagreements about Japanese immigration to the U.S. were resolved in 1907. The two were allies against Germany in World War I.

Akira Iriye is a Japanese-born American historian and orientalist. He is a historian of diplomatic history, international, and transnational history. He taught at University of Chicago and Harvard University until his retirement in 2005.

Ikuhiko Hata is a Japanese historian. He earned his PhD at the University of Tokyo and has taught history at several universities. He is the author of a number of influential and well-received scholarly works, particularly on topics related to Japan's role in the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

Daniel W. Drezner is an American political scientist. He is known for his scholarship and commentary on International Relations and International Political Economy.

Japan–Malaysia relations refers to bilateral foreign relations between the two countries Japan and Malaysia. The earliest recorded historical relation between the two nations are the trade relations between the Malacca Sultanate and the Ryūkyū Kingdom in the 15th century. Small numbers of Japanese settlers migrated to various parts of present-day Malaysia throughout the 19th century. This continued well into the 20th century, until relations reached an abrupt nadir with the rise of the Empire of Japan and its subsequent invasion and occupation of British Malaya and Borneo during World War II, during which the local populace endured often brutal Japanese military rule.

Henry Willard Denison was an American diplomat and lawyer, active in Meiji period Japan.

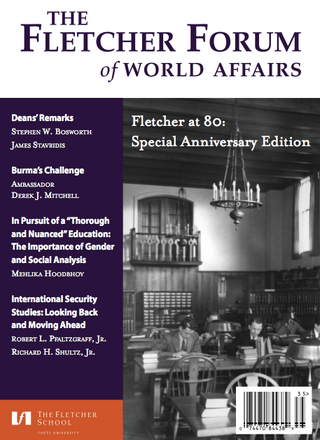

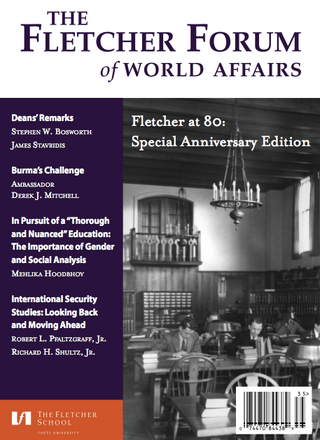

The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy is the graduate school of international affairs of Tufts University, in Medford, Massachusetts. Fletcher is one of America's oldest graduate schools of international relations. As of 2017, the student body numbered around 230, of whom 36 percent were international students from 70 countries, and around a quarter were U.S. minorities.

The history of China–Japan relations spans thousands of years through trade, cultural exchanges, friendships, and conflicts. Japan has deep historical and cultural ties with China; cultural contacts throughout its history have strongly influenced the nation – including its writing system architecture, cuisine, culture, literature, religion, philosophy, and law.

Kent E. Calder was the interim dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), serves as the director of the Edwin O. Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies, and is also the Edwin O. Reischauer Professor of East Asian Studies at SAIS. Calder previously served as the vice dean for faculty affairs and international research cooperation at SAIS.

Institute for Global Maritime Studies, also known as IGMS is a maritime studies non-profit organization dedicated to policy-oriented education and research.

Alan Michael Wachman was a scholar of East Asian politics and international relations, specializing in cross-strait relations and Sino-U.S. relations. He was a professor of international politics at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University. Previously he had been the co-director of the Johns Hopkins University-Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies in the PRC, and the president of China Institute in America.

The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs is a biannual peer-reviewed academic journal of international relations established in 1975. It is managed by students at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. It is also an online foreign policy forum with additional articles and interviews.

The bibliography covers the main scholarly books, and a few articles, dealing with the History of Japan

The history of Japanese foreign relations deals with the international relations in terms of diplomacy, economics and political affairs from about 1850 to 2000. The kingdom was largely isolated before the 1850s, with limited contacts through Dutch traders. The Meiji Restoration was a political revolution that installed a new leadership that was eager to borrow Western technology and organization. The government in Tokyo carefully monitored and controlled outside interactions. Japanese delegations to Europe brought back European standards which were widely imposed across the government and the economy. Trade flourished, and Japan rapidly industrialized. In the late 19th century Japan defeated China, and acquired numerous colonies, including Formosa and Okinawa. The rapid advances in Japanese military prowess led to the Russo-Japanese War, the first time a non-Western nation defeated a European power. Imperialism continued as it took control of Korea, and began moving into Manchuria. Its only military alliance was with Great Britain, from 1902 to 1923. In the First World War, it joined the Entente powers, and seized many German possessions in the Pacific and in China.

Japan participated in World War II from 1939 to 1945 as a member of the Axis. World War II and the Second Sino-Japanese War encapsulate a significant period in the history of the Empire of Japan, marked by significant military campaigns and geopolitical maneuvers across the Asia-Pacific region. Spanning from the early 1930s to 1945, Japan employed expansionist policies and aggressive military actions, including the invasion of the Republic of China, and the annexation of French Indochina.

East Asia–United States relations covers American relations with the region as a whole, as well as summaries of relations with China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and smaller places. It includes diplomatic, military, economic, social and cultural ties. The emphasis is on historical developments.