Isa Khan was the leader of the 16th-century Baro-Bhuiyan chieftains of Bengal. During his reign, he successfully unified the chieftains of Bengal and resisted the Mughal invasion of Bengal. It was only after his death that the region fell totally under Mughal control. He remains an iconic figure throughout West Bengal and Bangladesh as a symbol of his rebellious spirit and unity.

Sonargaon is a historic city in central Bangladesh. It corresponds to the Sonargaon Upazila of Narayanganj District in Dhaka Division.

Sandwip is an island located along the southeastern coast of Bangladesh in the Chittagong District. Along with the island of Urir Char, it is part of the Sandwip Upazila.

The history of Bengal is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the surrounding regions of South Asia and Southeast Asia. It includes modern-day Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Karimganj district, located in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, at the apex of the Bay of Bengal and dominated by the fertile Ganges delta. The region was known to the ancient Greeks and Romans as Gangaridai, a powerful kingdom whose war elephant forces led the withdrawal of Alexander the Great from India. Some historians have identified Gangaridai with other parts of India. The Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers act as a geographic marker of the region, but also connects the region to the broader Indian subcontinent. Bengal, at times, has played an important role in the history of the Indian subcontinent.

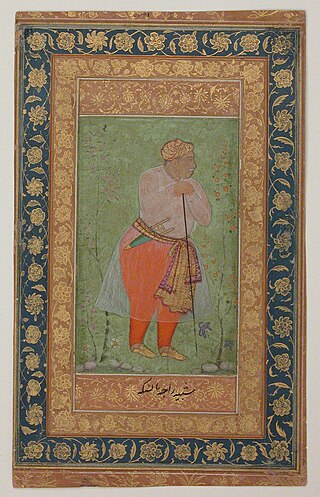

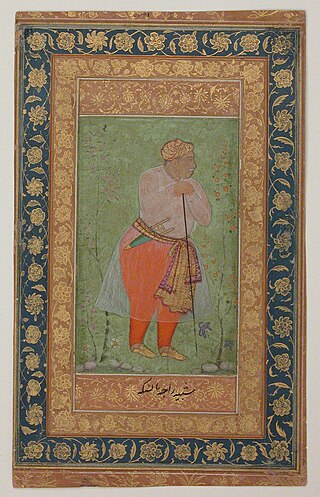

RajaMan Singh I was the 24th Maharaja of Kingdom of Amber from 1589 to 1614. He also served as the Subahdar of Bengal for three terms from 1595 to 1606 and the Subahdar of Kabul from 1585 to 1586. He served in the Mughal Army under Emperor Akbar. Man Singh fought sixty-seven important battles in Kabul, Balkh, Bukhara, Bengal and Central and Southern India. He was well versed in the battle tactics of both the Rajputs as well as the Mughals. He is commonly considered to be one of the Navaratnas, or the nine (nava) gems (ratna) of the royal court of Akbar.

Mirza Abu Talib, better known as Shaista Khan, was a general and the Subahdar of Mughal Bengal, he was maternal uncle to the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, he acted as a key figure during his reign, Shaista Khan initially governed the Deccan, where he clashed with the Maratha ruler Shivaji, However, he was most notable for his tenure as the governor of Bengal from 1664 to 1688, Under Shaista Khan's authority, the city of Dhaka and Mughal power in the province attained its greatest heights. His achievements include constructions of notable mosques such as the Sat Gambuj Mosque and masterminding the conquest of Chittagong. Shaista Khan was also responsible for sparking the outbreak of the Anglo-Mughal War with the English East India Company.

Bangladesh's military history is intertwined with the history of a larger region, including present-day India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan and Myanmar. The country was historically part of Bengal – a major power in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Pratapaditya Guha was a rebellious Kayashtha king of Jessore of lower Bengal, before being defeated by the Mughal Empire. He was eulogized by 19th and 20th century Bengali historians as a resistor against Mughal in Jessore but the statements are still debated.

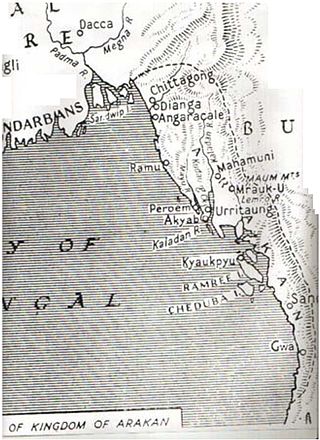

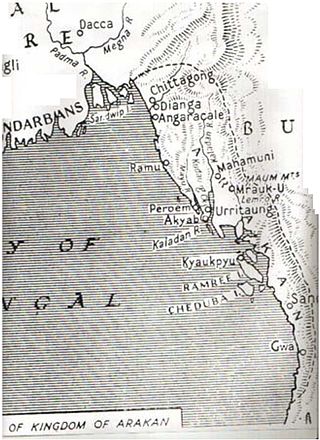

The Kingdom of Mrauk-U was a kingdom that existed on the Arakan littoral from 1429 to 1785. Based in the capital Mrauk-U, near the eastern coast of the Bay of Bengal, the kingdom ruled over what is now Rakhine State, Myanmar and southern part of Chittagong Division, Bangladesh. Though started out as a protectorate of the Bengal Sultanate from 1429 to 1531, Mrauk-U went on to conquer Chittagong with the help of the Portuguese. It twice fended off the Toungoo Burma's attempts to conquer the kingdom in 1546–1547, and 1580–1581. At its height of power, it briefly controlled the Bay of Bengal coastline from the Sundarbans to the Gulf of Martaban from 1599 to 1603. In 1666, it lost control of Chittagong after a war with the Mughal Empire. Its reign continued until 1785, when it was conquered by the Konbaung dynasty of Burma.

The Bengal Subah, also referred to as Mughal Bengal, was the largest subdivision of Mughal India encompassing much of the Bengal region, which includes modern-day Bangladesh, the Indian state of West Bengal, and some parts of the present-day Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha between the 16th and 18th centuries. The state was established following the dissolution of the Bengal Sultanate, a major trading nation in the world, when the region was absorbed into the Mughal Empire. Bengal was the wealthiest region in the Indian subcontinent.

The city of Chattogram (Chittagong) is traditionally centred around its seaport which has existed since the 4th century BCE. One of the world's oldest ports with a functional natural harbor for centuries, Chittagong appeared on ancient Greek and Roman maps, including on Ptolemy's world map. Chittagong port is the oldest and largest natural seaport and the busiest port of Bay of Bengal. It was located on the southern branch of the Silk Road. The city was home to the ancient independent Buddhist kingdoms of Bengal like Samatata and Harikela. It later fell under of the rule of the Gupta Empire, the Gauda Kingdom, the Pala Empire, the Chandra Dynasty, the Sena Dynasty and the Deva Dynasty of eastern Bengal. Arab Muslims traded with the port from as early as the 9th century. Historian Lama Taranath is of the view that the Buddhist king Gopichandra had his capital at Chittagong in the 10th century. According to Tibetan tradition, this century marked the birth of Tantric Buddhism in the region. The region has been explored by numerous historic travellers, most notably Ibn Battuta of Morocco who visited in the 14th century. During this time, the region was conquered and incorporated into the independent Sonargaon Sultanate by Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah in 1340 AD. Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah constructed a highway from Chittagong to Chandpur and ordered the construction of many lavish mosques and tombs. After the defeat of the Sultan of Bengal Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah in the hands of Sher Shah Suri in 1538, the Arakanese Kingdom of Mrauk U managed to regain Chittagong. From this time onward, until its conquest by the Mughal Empire, the region was under the control of the Portuguese and the Magh pirates for 128 years.

Chittagong, the second largest city and main port of Bangladesh, was home to a thriving trading post of the Portuguese Empire in the East in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Portuguese first arrived in Chittagong around 1528 and left in 1666 after the Mughal conquest. It was the first European colonial enclave in the historic region of Bengal.

Khawāja Uthmān Khān Lōhānī, popularly known as Khwaja Usman, was a Pashtun chieftain and warrior based in northeastern Bengal. As one of the Baro-Bhuyans, he was a zamindar ruling over the northern parts of Bengal including Greater Mymensingh and later in South Sylhet. He was a formidable opponent to Man Singh I and the Mughal Empire, and was the last of the Afghan chieftains and rulers in Bengal. His defeat led to the surrender of all the remaining Pashtuns as well as the incorporation of the Sylhet region into the Bengal Subah. He is described as the most romantic figure in the history of Bengal. His biography can be found in the Baharistan-i-Ghaibi, Tuzk-e-Jahangiri as well as the Akbarnama.

Rajdhar Manikya I, also spelt Rajadhara Manikya, was the Maharaja of Tripura from 1586 to 1600. Formerly a warrior-prince who fought with distinction during his father's reign, upon his own ascension to the throne, Rajdhar showed little interest in such matters, instead becoming occupied with religious pursuits. The decline of Tripura is thought to have begun during his reign.

The Greater Noakhali district region predominantly includes the districts of Noakhali, Feni and Lakshmipur, although historically included the island of Sandwip in Bay of Bengal. The history of the undivided Noakhali district region begins with the existence of civilisation in the villages of Shilua and Bhulua. Bhulua became a focal point of Bengal during the Buddhist and Hindu kingdoms of Pundra, Harikela and Samatata leading it to become the initial name of the region as a whole. The medieval Kingdom of Bhulua enjoyed autonomy under the Twipra Kingdom and Bengal Sultanate before being conquered by the Mughal Empire. At the beginning of the 17th century, Portuguese pirates led by Sebastian Gonzales took control of the ara but were later defeated by Governor Shaista Khan. Affected by floodwaters, the capital of the region was swiftly moved to a new place known as Noakhali, from which the region presently takes its name. By 1756, the British East India Company had dominated and started to establish several factories in the region. The headquarters was once again moved in 1951, to Maijdee, as a result of Noakhali town vanishing due to fluvial erosion.

Dilwar Khan, popularly known as Raja Dilal, was the last independent ruler of Sandwip, an island in present-day Bangladesh. His reputation as a strong and charitable ruler has made him considered to be the Robin Hood of Southeast Bengal, robbing the rich and rewarding the poor. His legacy remains popular today, and is engraved in local folklore and strange legends in Sandwip. He has been considered the most influential Bengali Muslim ruler of the 17th century.

Shaykh ʿAbdul Wāḥid was a military general of the Mughal Empire during the reign of Jahangir, and played an important role in defeating Bahadur Ghazi, who was among the rebellious Baro-Bhuiyans of Bengal. He is celebrated as the Mughal conqueror of Bhulua as he was the chief commander of its expedition. His administration of the Bhulua frontier involved suppressing multiple Arakanese invasions, later earning him the title of Sarḥad Khān.

Kirtinarayan Basu, also spelt Kirti Narayan Basu, was the fifth raja of medieval Chandradwip, a zamindari which covered much of the Barisal Division of present-day Bangladesh.

The Conquest of Bhulua refers to the 17th-century Mughal conquest of the Bhulua Kingdom, which covered much of the present-day Noakhali region of Bangladesh. The campaign was led by Shaykh Abdul Wahid, under the orders of Islam Khan I, against Raja Ananta Manikya in 1613. The conquest of Bhulua allowed the Mughals to successfully penetrate through southeastern Bengal and conquer Chittagong and parts of Arakan.

Mughal conquest of Chittagong refers to the conquest of Chittagong in 1666. On 27 January 1666 AD, the Arakan Kingdom of Mrauk U was defeated by the Mughal forces under the command of Buzurg Ummed Khan, the son of Mughal Subedar Shaista Khan.