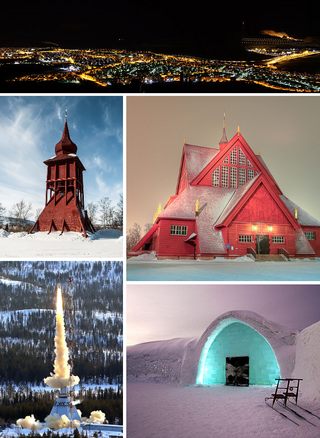

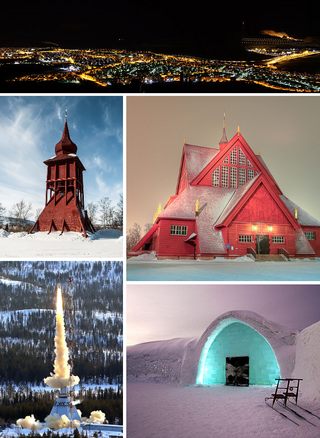

Kiruna is the northernmost city in Sweden, situated in the province of Lapland. It had 17,002 inhabitants in 2016 and is the seat of Kiruna Municipality in Norrbotten County. The city was originally built in the 1890s to serve the Kiruna Mine.

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the form of magnetite (Fe

3O

4, 72.4% Fe), hematite (Fe

2O

3, 69.9% Fe), goethite (FeO(OH), 62.9% Fe), limonite (FeO(OH)·n(H2O), 55% Fe), or siderite (FeCO3, 48.2% Fe).

Skarns or tactites are coarse-grained metamorphic rocks that form by replacement of carbonate-bearing rocks during regional or contact metamorphism and metasomatism. Skarns may form by metamorphic recrystallization of impure carbonate protoliths, bimetasomatic reaction of different lithologies, and infiltration metasomatism by magmatic-hydrothermal fluids. Skarns tend to be rich in calcium-magnesium-iron-manganese-aluminium silicate minerals, which are also referred to as calc-silicate minerals. These minerals form as a result of alteration which occurs when hydrothermal fluids interact with a protolith of either igneous or sedimentary origin. In many cases, skarns are associated with the intrusion of a granitic pluton found in and around faults or shear zones that commonly intrude into a carbonate layer composed of either dolomite or limestone. Skarns can form by regional or contact metamorphism and therefore form in relatively high temperature environments. The hydrothermal fluids associated with the metasomatic processes can originate from a variety of sources; magmatic, metamorphic, meteoric, marine, or even a mix of these. The resulting skarn may consist of a variety of different minerals which are highly dependent on both the original composition of the hydrothermal fluid and the original composition of the protolith.

Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara Aktiebolag (LKAB) is a state-owned Swedish mining company. The company mines iron ore at Kiruna and at Malmberget in northern Sweden. The company was established in 1890, and has been 100% state-owned since the 1950s. The iron ore is processed to pellets and sinter fines, which are transported by Iore trains (Malmbanan) to the harbours at Narvik and Luleå and to the steel mill at Luleå (SSAB). Their production is sold throughout much of the world, with the principal markets being European steel mills, as well as North Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. LKAB's mines supply at least 80% of Europe's iron ore.

Various theories of ore genesis explain how the various types of mineral deposits form within Earth's crust. Ore-genesis theories vary depending on the mineral or commodity examined.

The Emily Ann and Maggie Hays nickel deposits are situated 117 km west of the town of Norseman, Western Australia, within the Lake Johnston Greenstone Belt.

The Broken Hill Ore Deposit is located underneath Broken Hill in western New South Wales, Australia, and is the namesake for the town. It is arguably the world's richest and largest zinc-lead ore deposit.

Svappavaara is a locality situated in Kiruna Municipality, Norrbotten County, Sweden with 417 inhabitants in 2010. It is a mining village. Mining was started around 1650. Large scale iron mining started in 1965. The mine was closed in 1983, but enrichment of iron ore from the mine at Kiruna is still going on. The mine is owned by LKAB, and there is an ongoing project to open it again for production around year 2015.

Kiirunavaara is a mountain situated in Kiruna Municipality in Norrbotten County, Sweden. It contains one of the largest and richest bodies of iron ore in the world.

Johan Olof Hjalmar Lundbohm was a Swedish geologist and chemist and the first managing director of LKAB in Kiruna. He made a strong contribution to the design of the new community of Kiruna in Lapland.

Iron oxide copper gold ore deposits (IOCG) are important and highly valuable concentrations of copper, gold and uranium ores hosted within iron oxide dominant gangue assemblages which share a common genetic origin.

The Malmberget mine is one of the largest iron ore mines in the world. The mine is located in Malmberget in Norrbotten County, Lapland, it is owned by Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara AB (LKAB). The mine has an annual production capacity of over 5 million tonnes of iron ore and has reserves amounting to 350 million tonnes of ore grading 43.8% iron, resulting 153.3 million tonnes of iron. In 2009, the mine produced 4.3 million tonnes of iron.

The Atacama Fault Zone (AFZ) is an extensive system of faults cutting across the Chilean Coastal Cordillera in Northern Chile between the Andean Mountain range and the Pacific Ocean. The fault system is north–south striking and runs for more than 1100 km North and up to 50 km in width through the Andean forearc region. The zone is a direct result of the ongoing subduction of the Eastward moving Nazca plate beneath the South American plate and is believed to have formed in the Early Jurassic during the beginnings of the Andean orogeny. The zone can be split into 3 regions: the North, Central and South.

El Laco is a volcanic complex in the Antofagasta Region of Chile. It is directly south of the Cordón de Puntas Negras volcanic chain. Part of the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes, it is a group of seven stratovolcanoes and a caldera. It is about two million years old. The main summit of the volcano is a lava dome called Pico Laco, which is variously reported to be 5,325 metres (17,470 ft) or 5,472 metres (17,953 ft) high. The edifice has been affected by glaciation, and some reports indicate that it is still fumarolically active.

A primary mineral is any mineral formed during the original crystallization of the host igneous primary rock and includes the essential mineral(s) used to classify the rock along with any accessory minerals. In ore deposit geology, hypogene processes occur deep below the Earth's surface, and tend to form deposits of primary minerals, as opposed to supergene processes that occur at or near the surface, and tend to form secondary minerals.

The mining industry in Sweden has a history dating back 6,000 years.

The Chilean Iron Belt is a geological province rich in iron ore deposits in northern Chile. It extends as a north-south beld along the western part of the Chilean regions of Coquimbo and Atacama, chiefly between the cities of La Serena and Taltal. The belt follows much of the Atacama Fault System and is about 600 km long and 25 km broad.

Kiruna porphyry is a group of igneous rocks found near Kiruna in northernmost Sweden. The Kiruna Porphyry formed 1,880 to 1,900 million years ago during the Paleoproterozoic Era in connection to the Svecofennian orogeny.

Tibor Parák was a Hungarian geologist known for his mineral explorations and academic contributions to economic geology. Parák arrived in Sweden from Soviet-occupied Hungary as a refugee in 1956.

The Mertainen is an iron ore deposit and mine in Lapland, Sweden, Sweden. It is located about 30 km southeast of the town of Kiruna. In December 2016 Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara AB closed the mine for indefinite time. Re-opening the mine remains a possibility according to LKAB executive Magnus Arnkvist.