Rodney Peter Croome AM is an Australian LGBT rights activist and academic. He worked on the campaign to decriminalise homosexuality in Tasmania, was a founder of Australian Marriage Equality, and currently serves as the spokesperson for the Tasmanian Gay and Lesbian Rights Group and a spokesperson for LGBT advocacy group Just.Equal.

Human rights in Australia have largely been developed by the democratically elected Australian Parliament through laws in specific contexts and safeguarded by such institutions as the independent judiciary and the High Court, which implement common law, the Australian Constitution, and various other laws of Australia and its states and territories. Australia also has an independent statutory human rights body, the Australian Human Rights Commission, which investigates and conciliates complaints, and more generally promotes human rights through education, discussion and reporting.

New Zealand lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights are some of the most extensive in the world. The protection of LGBT rights is advanced, relative to other countries in Oceania, and among the most liberal in the world, with the country being the first in the region to legalise same-sex marriage.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Australia rank among the highest in the world; having significantly advanced over the latter half of the 20th century and early 21st century. Opinion polls and the Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey indicate widespread popular support for same-sex marriage within the nation. Australia in 2018, in fact was the last of the Five Eyes set of countries - that consisted of namely Canada (2005), New Zealand (2013), United Kingdom (2014) and the United States (2015) to legalize same-sex marriage. A 2013 Pew Research poll found that 79% of Australians agreed that homosexuality should be accepted by society, making it the fifth-most supportive country surveyed in the world. With its long history of LGBTQ activism and annual Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras festival, Sydney has been named one of the most gay-friendly cities in the world.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Australia since 9 December 2017. Legislation to allow it, the Marriage Amendment Act 2017, passed the Parliament of Australia on 7 December 2017 and received royal assent from Governor-General Peter Cosgrove the following day. The law came into effect on 9 December, immediately recognising overseas same-sex marriages. The first same-sex wedding under Australian law was held on 15 December 2017. The passage of the law followed a voluntary postal survey of all Australians, in which 61.6% of respondents supported legalisation of same-sex marriage.

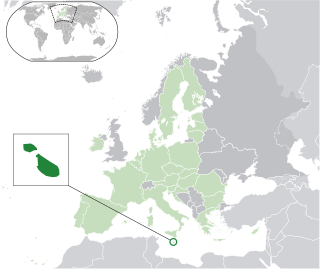

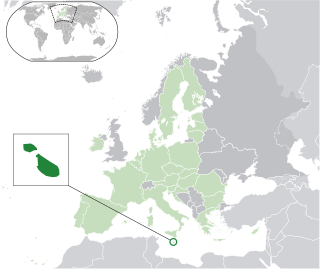

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Malta rank among the highest in the world. Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the rights of the LGBTQ community received more awareness and same-sex sexual activity was legalized on 29 January 1973. The prohibition was already dormant by the 1890s.

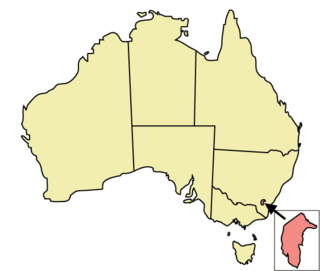

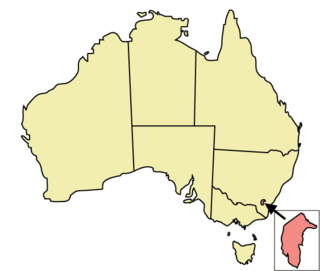

Toonen v. Australia was a landmark human rights complaint brought before the United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC) by Tasmanian resident Nicholas Toonen in 1994. The case resulted in the repeal of Australia's last sodomy laws when the Committee held that sexual orientation was included in the antidiscrimination provisions as a protected status under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Oceania is, like other regions, quite diverse in its laws regarding LGBT rights. This ranges from significant rights, including same-sex marriage – granted to the LGBT+ community in New Zealand, Australia, Guam, Hawaii, Easter Island, Northern Mariana Islands, Wallis and Futuna, New Caledonia, French Polynesia and the Pitcairn Islands – to remaining criminal penalties for homosexual activity in six countries and one territory. Although acceptance is growing across the Pacific, violence and social stigma remain issues for LGBT+ communities. This also leads to problems with healthcare, including access to HIV treatment in countries such as Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands where homosexuality is criminalised.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Queensland have advanced significantly from the late 20th century onwards, in line with progress on LGBTQ rights in Australia nationally. 2019 polling on gay rights consistently showed that even in regional areas, Queensland is no more conservative about the subject than any other states.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people in the Australian state of New South Wales have most of the same rights and responsibilities as non-LGBTQ people.

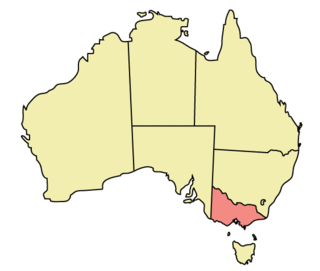

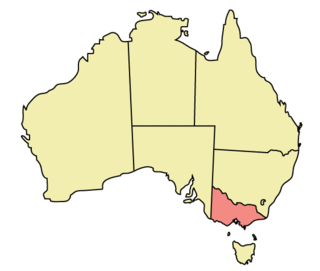

The Australian state of Victoria is regarded as one of the country's most progressive jurisdictions with respect to the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people. Victoria is the only state in Australia, that has implemented a LGBTIQA+ Commissioner.

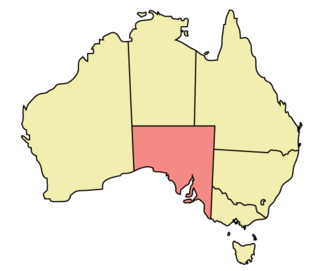

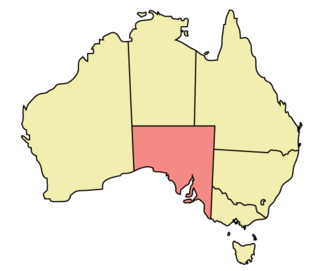

The rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Australian state of South Australia are advanced and well-established. South Australia has had a chequered history with respect to the rights of LGBT people. Initially, the state was a national pioneer of LGBT rights in Australia, being the first in the country to decriminalise homosexuality and to introduce a non-discriminatory age of consent for all sexual activity. Subsequently, the state fell behind other Australian jurisdictions in areas including relationship recognition and parenting, with the most recent law reforms regarding the recognition of same-sex relationships, LGBT adoption and strengthened anti-discrimination laws passing in 2016 and going into effect in 2017.

Australia is one of the most LGBTQ-friendly countries in the world. In a 2013 Pew Research poll, 79% of Australians agreed that homosexuality should be accepted by society, making it the fifth most supportive country in the survey behind Spain (88%), Germany (87%), and Canada and the Czech Republic. With a long history of LGBTQ rights activism and an annual three-week-long Mardi Gras festival, Sydney is considered one of the most gay-friendly cities in the world.

This article details the history of the LGBTQ rights movement in Australia, from the colonial era to the present day.

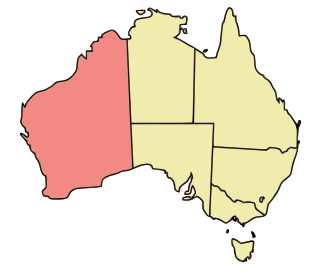

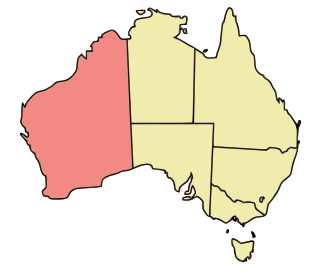

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBTQ) rights in Western Australia have seen significant progress since the beginning of the 21st century, with male sex acts legal since 1990 and the state parliament passing comprehensive law reforms in 2002. The state decriminalised male homosexual acts in 1990 and was the first to grant full adoption rights to LGBT couples in 2002.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in Australia's Northern Territory have the same legal rights as non-LGBTQ people. The liberalisation of the rights of LGBTQ people in Australia's Northern Territory has been a gradual process. Homosexual activity was legalised in 1984, with an equal age of consent since 2003. Same-sex couples are recognised as de facto relationships. There was no local civil union or domestic partnership registration scheme before the introduction of nationwide same-sex marriage in December 2017, following the passage of the Marriage Amendment Act 2017 by the Australian Parliament. The 2017 Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey, designed to gauge public support for same-sex marriage in Australia, returned a 60.6% "Yes" response in the territory. LGBTQ people are protected from discrimination by both territory and federal law, though the territory's hate crime law does not explicitly cover sexual orientation or gender identity. The territory was the last jurisdiction in Australia to legally allow same-sex couples to adopt children.

The Australian Capital Territory (ACT) is one of Australia's leading jurisdictions with respect to the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people. The ACT has made a number of reforms to territory law designed to prevent discrimination of LGBTQ people; it was the only state or territory jurisdiction in Australia to pass a law for same-sex marriage, which was later overturned by the High Court of Australia. The Australian Capital Territory, Victoria, Queensland and both South Australia and New South Wales representing a population of 85% on Australia – explicitly ban conversion therapy practices within their jurisdictions by recent legislation enacted. The ACT's laws also apply to the smaller Jervis Bay Territory.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) rights in the British Crown dependency of Jersey have evolved significantly since the early 1990s. Same-sex sexual activity was decriminalised in 1990. Since then, LGBTQ people have been given many more rights equal to that of heterosexuals, such as an equal age of consent (2006), the right to change legal gender for transgender people (2010), the right to enter into civil partnerships (2012), the right to adopt children (2012) and very broad anti-discrimination and legal protections on the basis of "sexual orientation, gender reassignment and intersex status" (2015). Jersey is the only British territory that explicitly includes "intersex status" within anti-discrimination laws. Same-sex marriage has been legal in Jersey since 1 July 2018.

Transgender rights in Australia have legal protection under federal and state/territory laws, but the requirements for gender recognition vary depending on the jurisdiction. For example, birth certificates, recognised details certificates, and driver licences are regulated by the states and territories, while Medicare and passports are matters for the Commonwealth.

This is a list of notable events in LGBT rights that took place in the 2010s.