Laconian vase painting is a regional style of Greek vase painting, produced in Laconia, the region of Sparta, primarily in the 6th century BC.

Contents

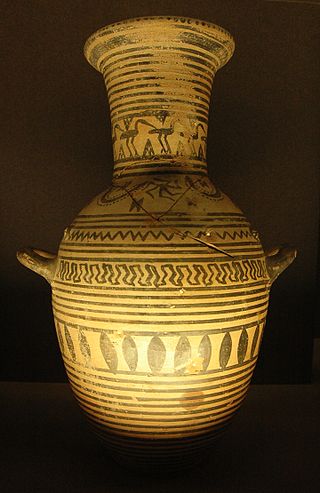

The first pottery with ornamental decoration produced in Laconia belongs to the Geometric period.

Laconian vase painting is a regional style of Greek vase painting, produced in Laconia, the region of Sparta, primarily in the 6th century BC.

The first pottery with ornamental decoration produced in Laconia belongs to the Geometric period.

Laconian pottery was discovered in considerable amounts in the 19th century, mostly in Etruscan graves. Initially, it was falsely interpreted as produce of Cyrene, where similar material had been found. Thanks to British excavations undertaken since 1906 in the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia at Sparta, the real origin was later recognised. In 1934, Edward Arthur Lane collated the known finds, and became the first archaeologist to distinguish several individual Laconian painters. [1] In 1954, Brian B. Shefton examined new finds. He reduced the number of painters assumed until then by half. [2] The remainder were the Arkesilas Painter, the Hunt Painter and the Rider Painter. In 1958 and 1959, important new finds from Taras were published. Additionally, a significant number of Laconian vases were discovered on Samos. Conrad Michael Stibbe re-examined all available material and published his results in 1972. [3] He distinguished five major and three minor vase painters, adding to the three painters mentioned above the Boreades Painter, the Naukratis Painter, the Allard-Pierson Painter, the Typhon painter and the Chimeira Painter. Other scholars have recognised further artists, such as the Painter of the Taranto Fishes or the Grammichele Painter.

The clay of Laconian vases is orange, quite refined and of high quality. The vessels were wholly or partially covered with a yellowish-white slip. The first vases of notable quality were made around 580 BC. The leading shape of Laconian pottery is the kylix . Rim and bowl were initially sharply distinguished, but by the middle of the century, the transition was smoother. The earliest cups had no foot, later, a short squat foot was added. In the next phase, around 570 BC, it became higher, only to turn shorter and squatter again near the end of the productive period. Laconian vases were quite widely distributed: specimens have been found at Marseille, Taranto, Reggio di Calabria, Cumae, Nola, Naukratis, Sardes, Rhodes, Samos, Etruria and nearly all over the Greek mainland. On Samos they were at times more common than imports from Corinth, presumably because of the close political links between Sparta and Samos. Apart from cups, amphorae, hydriai , Laconian kraters, volute kraters, lebetes , lakaina and aryballoi were produced.

It is likely that Laconian pottery was produced by perioikoi but this is nor certain. Although we know of Spartan citizen families being involved in craft activities of direct importance to warfare, it is unlikely that pottery production was considered among those. Helots worked exclusively in agriculture. Another theory proposes that the potters was made by itinerant potters from East Greece. This would be suggested by the strong East Greek influence on the paintings, especially those by the Boreades Painter. Production was aimed at the local market, and to some export. Cups were mostly made for export, the typical Spartan drinking vessel lakaina was mainly found in Laconia. The work of some of the painters has not so far been found in Laconia at all, indicating that some workshops entirely concentrated on export. It can be assumed that the producers were potter-painters, i.e. that both stages of production were performed by the same individuals, as certain specific features in the vase shapes are only found on works ascribed to a single painter. No workshops have so far been located; perhaps they were in peroikic settlements not yet excavated. Neither potters nor painters signed their vases. In fact, inscriptions are quite rare and only ever used to name painted figures.

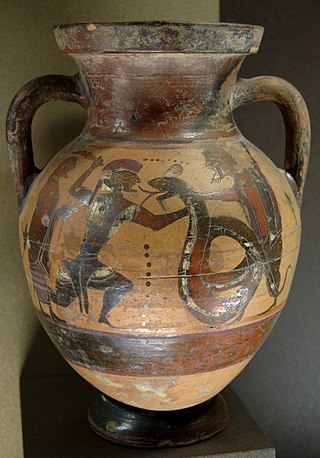

The painters used additional colours, such as red and white, quite extensively, but also very carefully, thereby increasing the decorative effect. Earlier than other local styles, e.g. those of Corinth, Attica or East Greece, the figurally decorated interior of the cup became the carrier of the main image. Around 570 BC, perhaps under the influence of East Greek plates, the Boreades Painter subdivided the interior image into segments. Such zones were to become typical of Laconian vase painting. He also introduced the typical Laconian tripartite subdivision of the exterior surface of the cup bowl (pomegranates, flames and rays). The painters depicted scenes of everyday life, hunting scenes, symposia and motifs related to warfare. Additionally, mythological imagery was common. Among it, the most popular figure was Herakles, usually shown in combat with animals or monsters. Other motifs include Troilos and Achilles, Atlas, the hunt for the Calydonian boar, the return of Hephaistos to Mount Olympus, Prometheus and the blinding of Polyphemus. The most frequently depicted gods are Zeus and Poseidon. The interior image can also be of a gorgon. Images connected to the Trojan and Theban cycles of myth are also common. Special Laconian features are, for example, a horseman with a volute tendril growing from his head, or an image of the nymph Kyrene. Some vases were merely covered in shiny slip, or painted with only few ornaments.

The chronology developed by scholars primarily relies on finds from Taras and Tokra. The floruit of Laconian vase painting is usually placed in the period between 575 and 525 BC. Another important piece of chronological evidence is provided by the depiction of Arkesilaos II on the Arkesilas Cup, the name vase of the Arkesilas Painter. It was probably produced during that king's reign. The usually very high-quality products of Laconian vase painting are among the most significant Greek vases.

There are around eighty-one vases or fragments of Laconian red-figure vase painting, produced from c.430 for thirty to forty years. [4] The majority of examples were found by Konstantinos Rhomaios at a Laconian settlement at Analipsis hill near Vourvoura during surface survey in 1899-1900, and then in excavations in the undertaken in early 1950s. [5] [6] [7] The rest of the known Laconian red-figure examples are from Sparta, [8] and the Tomb of the Laconians in the Athenian Kerameikos. [9] [10] Notable examples of the technique include what might be a depiction of a Karneia dancer from the Tomb of the Laconians in Athenian Kerameikos. Other scenes depicted include local mythology and ritual, such as the birth of Helen, Herakles, Athena, Thetis with the arms of Achilles, and Dionysian scenes and a Papsilenos, as well as youthful athletics and battle scenes. The Laconian pottery from the settlement at Analipsis hill was associated with offerings for domestic cult, and in the case of a fragment showing Dionysos and two maenads, as offerings found near the altar of a Classical building interpreted as a local sanctuary. [10]

Laconia or Lakonia is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word laconic—to speak in a blunt, concise way—is derived from the name of this region, a reference to the ancient Spartans who were renowned for their verbal austerity and blunt, often pithy remarks.

Pottery, due to its relative durability, comprises a large part of the archaeological record of ancient Greece, and since there is so much of it, it has exerted a disproportionately large influence on our understanding of Greek society. The shards of pots discarded or buried in the 1st millennium BC are still the best guide available to understand the customary life and mind of the ancient Greeks. There were several vessels produced locally for everyday and kitchen use, yet finer pottery from regions such as Attica was imported by other civilizations throughout the Mediterranean, such as the Etruscans in Italy. There were a multitude of specific regional varieties, such as the South Italian ancient Greek pottery.

Black-figure pottery painting, also known as the black-figure style or black-figure ceramic, is one of the styles of painting on antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th and 5th centuries BCE, although there are specimens dating in the 2nd century BCE. Stylistically it can be distinguished from the preceding orientalizing period and the subsequent red-figure pottery style.

Red-figure pottery is a style of ancient Greek pottery in which the background of the pottery is painted black while the figures and details are left in the natural red or orange color of the clay.

The Naucratis Painter was a Laconian vase painter of the mid-sixth century BC. Naucratis was a Greek trading post (emporion) in Egypt. Two fragments of a kylix found in the Demeter Sanctuary, Cyrene, show that the Naucratis Painter was literate, and the form of a three-stroke iota suggests, moreover, that he was a foreigner in Laconia.

The Pioneer Group is a term used by scholars for a number of vase painters working in the potters' quarter of Kerameikos in ancient Athens around the beginning of the 5th century BC, around the time of the emergence of red-figure vase painting, which soon displaced the previously dominant black-figure style.

White-ground technique is a style of white ancient Greek pottery and the painting in which figures appear on a white background. It developed in the region of Attica, dated to about 500 BC. It was especially associated with vases made for ritual and funerary use, if only because the painted surface was more fragile than in the other main techniques of black-figure and red-figure vase painting. Nevertheless, a wide range of subjects are depicted.

Geometric art is a phase of Greek art, characterized largely by geometric motifs in vase painting, that flourished towards the end of the Greek Dark Ages and a little later, c. 1050–700 BC. Its center was in Athens, and from there the style spread among the trading cities of the Aegean. The so-called Greek Dark Ages were considered to last from c. 1100 to 800 BC and include the phases from the Protogeometric period to the Middle Geometric I period, which Knodell (2021) calls Prehistoric Iron Age. The vases had various uses or purposes within Greek society, including, but not limited to, funerary vases and symposium vases.

South Italian is a designation for ancient Greek pottery fabricated in Magna Graecia largely during the 4th century BC. The fact that Greek Southern Italy produced its own red-figure pottery as early as the end of the 5th century BC was first established by Adolf Furtwaengler in 1893. Prior to that this pottery had been first designated as "Etruscan" and then as "Attic." Archaeological proof that this pottery was actually being produced in South Italy first came in 1973 when a workshop and kilns with misfirings and broken wares was first excavated at Metaponto, proving that the Amykos Painter was located there rather than in Athens.

The Arkesilas Painter was a Laconian vase painter active around 560 BC. He is considered one of the five great vase painters of Sparta.

The Rider Painter was a Laconian vase painter active between 560 and 530 BC. He is considered one of the five great vase painters of Sparta.

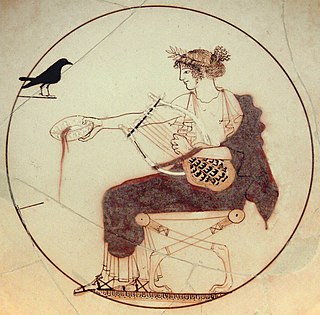

The Arkesilas Cup is a kylix by the Laconian vase painter known as the Arkesilas Painter, whose name vase it is. It depicts, and is thus named after, Arkesilaos II, king of Kyrene and is dated to about 565–560 BC.

Boeotian vase painting was a regional style of ancient Greek vase painting. Since the Geometric period, and up to the 4th century BC, the region of Boeotia produced vases with ornamental and figural painted decoration, usually of lesser quality than the vase paintings from other areas.

Euboean vase painting was a regional style of ancient Greek vase painting, prevalent on the island of Euboea.

The Pontic Group is a sub-style of Etruscan black-figure vase painting.

Samian vase painting was a regional style of ancient Greek vase painting; it formed part of East Greek vase painting.

Ionic vase painting was a regional style of ancient Greek vase painting.

Submycenaean pottery is a style of Ancient Greek pottery that is transitional between the preceding Mycenaean pottery and the subsequent styles of Greek vase painting, particularly the Protogeometric style. The vases from this period date between 1030 and 1000 BC.

This page lists topics related to ancient Greece.