Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal and destruction of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. About 31% of Earth's land surface is covered by forests at present. This is one-third less than the forest cover before the expansion of agriculture, with half of that loss occurring in the last century. Between 15 million to 18 million hectares of forest, an area the size of Bangladesh, are destroyed every year. On average 2,400 trees are cut down each minute. Estimates vary widely as to the extent of deforestation in the tropics. In 2019, nearly a third of the overall tree cover loss, or 3.8 million hectares, occurred within humid tropical primary forests. These are areas of mature rainforest that are especially important for biodiversity and carbon storage.

Land use is an umbrella term to describe what happens on a parcel of land. It concerns the benefits derived from using the land, and also the land management actions that humans carry out there. The following categories are used for land use: forest land, cropland, grassland, wetlands, settlements and other lands. The way humans use land, and how land use is changing, has many impacts on the environment. Effects of land use choices and changes by humans include for example urban sprawl, soil erosion, soil degradation, land degradation and desertification.

Landscape ecology is the science of studying and improving relationships between ecological processes in the environment and particular ecosystems. This is done within a variety of landscape scales, development spatial patterns, and organizational levels of research and policy. Landscape ecology can be described as the science of "landscape diversity" as the synergetic result of biodiversity and geodiversity.

Urban ecology is the scientific study of the relation of living organisms with each other and their surroundings in an urban environment. An urban environment refers to environments dominated by high-density residential and commercial buildings, paved surfaces, and other urban-related factors that create a unique landscape. The goal of urban ecology is to achieve a balance between human culture and the natural environment.

Environmental degradation is the deterioration of the environment through depletion of resources such as: quality of air, water and soil, the destruction of ecosystems, habitat destruction, the extinction of wildlife, and pollution. It is defined as any change or disturbance to the environment perceived to be deleterious or undesirable. The environmental degradation process amplifies the impact of environmental issues which leave lasting impacts on the environment.

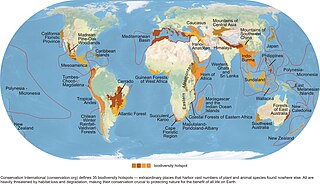

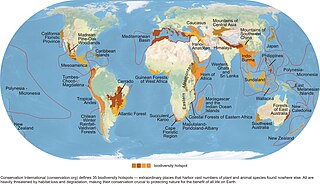

Habitat destruction occurs when a natural habitat is no longer able to support its native species. The organisms once living there have either moved to elsewhere or are dead, leading to a decrease in biodiversity and species numbers. Habitat destruction is in fact the leading cause of biodiversity loss and species extinction worldwide.

Environmental issues in Bolivia include deforestation caused by commercial agriculture, urbanization, and illegal logging, and biodiversity loss attributed to illegal wildlife trade, climate change, deforestation, and habitat destruction. Since 1990, Bolivia has experienced rapid urbanization raising concerns about air quality and water pollution.

Forest management is a branch of forestry concerned with overall administrative, legal, economic, and social aspects, as well as scientific and technical aspects, such as silviculture, forest protection, and forest regulation. This includes management for timber, aesthetics, recreation, urban values, water, wildlife, inland and nearshore fisheries, wood products, plant genetic resources, and other forest resource values. Management objectives can be for conservation, utilisation, or a mixture of the two. Techniques include timber extraction, planting and replanting of different species, building and maintenance of roads and pathways through forests, and preventing fire.

“Feminist political ecology” examines how power,gender, class, race, and ethnicity intersect with environmental ‘crises’, environmental change and human-environmental relations. Feminist political ecology emerged in the 1990s, drawing on theories from ecofeminism, feminist environmentalism, feminist critiques of development, postcolonial feminism, and post-structural critiques of political ecology. Specific areas in which feminist political ecology is focused are development, landscape, resource use, agrarian reconstruction, rural-urban transformation, intersectionality, subjectivities, embodiment, emotions, communication, situated knowledge, posthumanism, deconstructing theory-practice dichotomies, ethics of care and decolonial feminist political ecology. Feminist political ecologists suggest gender is a crucial variable – in relation to class, race and other relevant dimensions of political ecological life – in constituting access to, control over, and knowledge of natural resources.

In ecology, urban ecosystems are considered a ecosystem functional group within the intensive land-use biome. They are structurally complex ecosystems with highly heterogeneous and dynamic spatial structure that is created and maintained by humans. They include cities, smaller settlements and industrial areas, that are made up of diverse patch types. Urban ecosystems rely on large subsidies of imported water, nutrients, food and other resources. Compared to other natural and artificial ecosystems human population density is high, and their interaction with the different patch types produces emergent properties and complex feedbacks among ecosystem components.

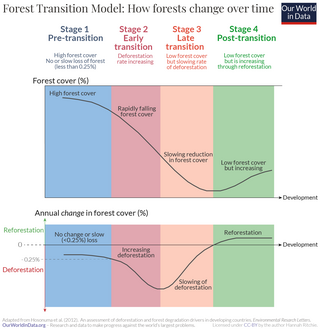

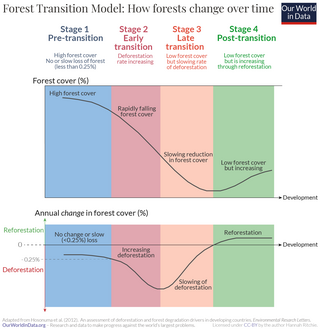

Forest transition refers to a geographic theory describing a reversal or turnaround in land-use trends for a given territory from a period of net forest area loss to a period of net forest area gain. The term "landscape turnaround" has also been used to represent a more general recovery of natural areas that is independent of biome type.

Brazil once had the highest deforestation rate in the world and in 2005 still had the largest area of forest removed annually. Since 1970, over 700,000 square kilometres (270,000 sq mi) of the Amazon rainforest have been destroyed. In 2001, the Amazon was approximately 5,400,000 square kilometres (2,100,000 sq mi), which is only 87% of the Amazon's original size. According to official data, about 729,000 km² have already been deforested in the Amazon biome, which corresponds to 17% of the total. 300,000 km² have been deforested in the last 20 years.

The extensive and rapid clearing of forests (deforestation) within the borders of Nigeria has significant impacts on both local and global scales.

Akure Forest Reserve is a protected area in southwest Nigeria, covering 66 km2 (25 sq mi). The Akure Forest Reserve, established in 1948 and spanning approximately 32 hectares. It was created with the primary aim of safeguarding the genetic diversity of the forest ecosystem. About 11.73% (8.2 km2) is estimated to be cleared for cocoa farming and other food crops. Aponmu and Owena Yoruba speaking communities owned the forest, though, there are also minor settlements surrounding the forest. They include Ipogun, Kajola/ Aponmu, Kajola, Ago Petesi, Akika Camp, Owena Town, Ibutitan/Ilaro Camp, Elemo Igbara Oke Camp and Owena Water new Dam.

At the global scale sustainability and environmental management involves managing the oceans, freshwater systems, land and atmosphere, according to sustainability principles.

Forest restoration is defined as "actions to re-instate ecological processes, which accelerate recovery of forest structure, ecological functioning and biodiversity levels towards those typical of climax forest", i.e. the end-stage of natural forest succession. Climax forests are relatively stable ecosystems that have developed the maximum biomass, structural complexity and species diversity that are possible within the limits imposed by climate and soil and without continued disturbance from humans. Climax forest is therefore the target ecosystem, which defines the ultimate aim of forest restoration. Since climate is a major factor that determines climax forest composition, global climate change may result in changing restoration aims. Additionally, the potential impacts of climate change on restoration goals must be taken into account, as changes in temperature and precipitation patterns may alter the composition and distribution of climax forests.

Deforestation is a primary contributor to climate change, and climate change affects the health of forests. Land use change, especially in the form of deforestation, is the second largest source of carbon dioxide emissions from human activities, after the burning of fossil fuels. Greenhouse gases are emitted from deforestation during the burning of forest biomass and decomposition of remaining plant material and soil carbon. Global models and national greenhouse gas inventories give similar results for deforestation emissions. As of 2019, deforestation is responsible for about 11% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon emissions from tropical deforestation are accelerating.

Due to its geographical and natural diversity, Indonesia is one of the countries most susceptible to the impacts of climate change. This is supported by the fact that Jakarta has been listed as the world's most vulnerable city, regarding climate change. It is also a major contributor as of the countries that has contributed most to greenhouse gas emissions due to its high rate of deforestation and reliance on coal power.

Climate change and cities are deeply connected. Cities are one of the greatest contributors and likely best opportunities for addressing climate change. Cities are also one of the most vulnerable parts of the human society to the effects of climate change, and likely one of the most important solutions for reducing the environmental impact of humans. The UN projects that 68% of the world population will live in urban areas by 2050. In the year 2016, 31 mega-cities reported having at least 10 million in their population, 8 of which surpassed 20 million people. However, secondary cities - small to medium size cities are rapidly increasing in number and are some of the fastest growing urbanizing areas in the world further contributing to climate change impacts. Cities have a significant influence on construction and transportation—two of the key contributors to global warming emissions. Moreover, because of processes that create climate conflict and climate refugees, city areas are expected to grow during the next several decades, stressing infrastructure and concentrating more impoverished peoples in cities.

Telecoupling is a strategy that comprehensively analyzes both the socioeconomic and environmental impacts over long distances. The concept of telecoupling is a logical extension of research on coupled human and natural systems, in which interactions occur within particular geographic locations. The telecoupling framework derives from the understanding that all land systems are connected through coupled human and natural systems, and these that social, ecological, and economic impacts are the result. The term telecoupling was first coined by Jianguo Liu as an evolution of the term teleconnection. While teleconnection makes reference to atmospheric sciences only, telecoupling references the integration of multiple scientific disciplines including social science, environmental science, natural science, and systems science. The integration of these dynamic fields of science is what allows the telecoupling framework to comprehensively analyze distal connections that have been previously understudied and unacknowledged.