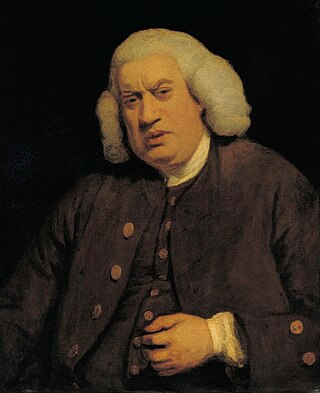

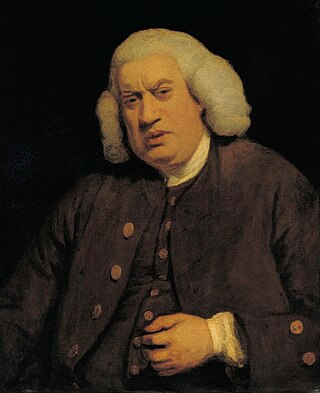

Samuel Johnson, often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography calls him "arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history".

A Dictionary of the English Language, sometimes published as Johnson's Dictionary, was published on 15 April 1755 and written by Samuel Johnson. It is among the most influential dictionaries in the history of the English language.

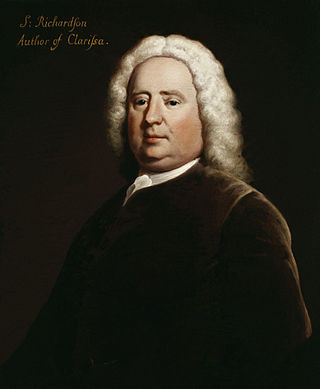

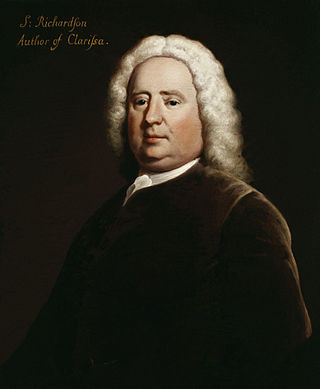

Samuel Richardson was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740), Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady (1748) and The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753). He printed almost 500 works, including journals and magazines, working periodically with the London bookseller Andrew Millar. Richardson had been apprenticed to a printer, whose daughter he eventually married. He lost her along with their six children, but remarried and had six more children, of whom four daughters reached adulthood, leaving no male heirs to continue the print shop. As it ran down, he wrote his first novel at the age of 51 and joined the admired writers of his day. Leading acquaintances included Samuel Johnson and Sarah Fielding, the physician and Behmenist George Cheyne, and the theologian and writer William Law, whose books he printed. At Law's request, Richardson printed some poems by John Byrom. In literature, he rivalled Henry Fielding; the two responded to each other's literary styles.

Thomas Carlyle was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher from the Scottish Lowlands. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature, and philosophy.

John Wilson Croker was an Anglo-Irish statesman and author.

Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, was a British statesman, diplomat, man of letters, and an acclaimed wit of his time.

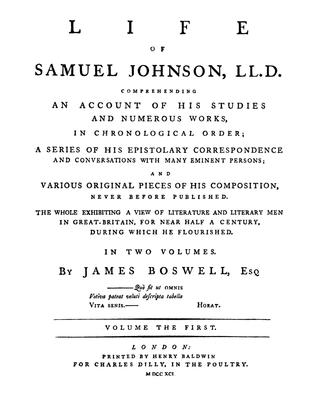

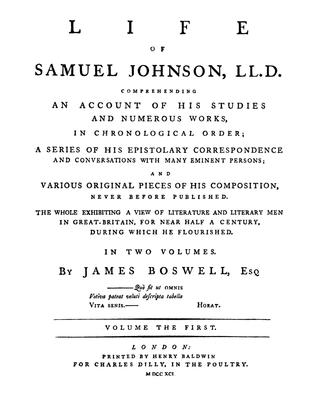

The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (1791) by James Boswell is a biography of English writer Samuel Johnson. The work was from the beginning a critical and popular success, and represents a landmark in the development of the modern genre of biography. It is notable for its extensive reports of Johnson's conversation. Many have called it the greatest biography written in English, but some modern critics object that the work cannot be considered a proper biography. Boswell's personal acquaintance with his subject began in 1763, when Johnson was 54 years old, and Boswell covered the entirety of Johnson's life by means of additional research. The biography takes many critical liberties with Johnson's life, as Boswell makes various changes to Johnson's quotations and even censors many comments. Nonetheless, the book is valued as both an important source of information on Johnson and his times, as well as an important work of literature.

Bardolatry is excessive admiration of William Shakespeare. Shakespeare has been known as "the Bard" since the eighteenth century. One who idolizes Shakespeare is known as a bardolator. The term bardolatry, derived from Shakespeare's sobriquet "the Bard of Avon" and the Greek word latria "worship", was coined by George Bernard Shaw in the preface to his collection Three Plays for Puritans published in 1901. Shaw professed to dislike Shakespeare as a thinker and philosopher because Shaw believed that Shakespeare did not engage with social problems as Shaw did in his own plays.

Jane Baillie Carlyle was a Scottish writer and the wife of Thomas Carlyle.

Andrew Warren Sledd was an American theologian, university professor and university president. A native of Virginia, he was the son of a prominent Methodist minister, and was himself ordained as a minister after earning his bachelor's and master's degrees. He later earned a second master's degree and his doctorate.

London is a poem by Samuel Johnson, produced shortly after he moved to London. Written in 1738, it was his first major published work. The poem in 263 lines imitates Juvenal's Third Satire, expressed by the character of Thales as he decides to leave London for Wales. Johnson imitated Juvenal because of his fondness for the Roman poet and he was following a popular 18th-century trend of Augustan poets headed by Alexander Pope that favoured imitations of classical poets, especially for young poets in their first ventures into published verse.

The Vanity of Human Wishes: The Tenth Satire of Juvenal Imitated is a poem by the English author Samuel Johnson. It was written in late 1748 and published in 1749. It was begun and completed while Johnson was busy writing A Dictionary of the English Language and it was the first published work to include Johnson's name on the title page.

Irene is a Neoclassical tragedy written between 1726 and 1749 by Samuel Johnson. It has the distinction of being the work Johnson considered his greatest failure. Since his death, the critical consensus has been that he was right to think so.

A Biographical Sketch of Dr Samuel Johnson was written by Thomas Tyers for The Gentleman's Magazine's December 1784 issue. The work was written immediately after the death of Samuel Johnson and is the first postmortem biographical work on the author. The first full length biography was written by John Hawkins and titled Life of Samuel Johnson.

The Plays of William Shakespeare was an 18th-century edition of the dramatic works of William Shakespeare, edited by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. Johnson announced his intention to edit Shakespeare's plays in his Miscellaneous Observations on Macbeth (1745), and a full Proposal for the edition was published in 1756. The edition was finally published in 1765.

The health of Samuel Johnson has been a focus of the biographical and critical analysis of his life. His medical history was well documented by Johnson and his friends, and those writings have allowed later critics and doctors to infer diagnoses of conditions that were unknown in Johnson's day.

Samuel Johnson was an English author born in Lichfield, Staffordshire. He was a sickly infant who early on began to exhibit the tics that would influence how people viewed him in his later years. From childhood he displayed great intelligence and an eagerness for learning, but his early years were dominated by his family's financial strain and his efforts to establish himself as a school teacher.

Robert Potter was an English clergyman of the Church of England and a translator, poet, critic and pamphleteer. He established the convention of using blank verse for Greek hexameters and rhymed verse for choruses. His 1777 English version of the plays of Aeschylus was frequently reprinted and the only one available for the next 50 years.

The Imaginary Library: An Essay on Literature and Society is a 1982 book by American literary critic and professor Alvin Kernan. In the book, Kernan considers literature as a social institution and considers ways in which the reigning Romantic conception of literature, which has dominated Western culture for 200 years, has fallen into decline due to changes in society.