Related Research Articles

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical genomes, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction; this reproduction of an organism by itself without a mate is known as parthenogenesis. In the field of biotechnology, cloning is the process of creating cloned organisms of cells and of DNA fragments.

Dolly was a female Finn-Dorset sheep and the first mammal that was cloned from an adult somatic cell. She was cloned by associates of the Roslin Institute in Scotland, using the process of nuclear transfer from a cell taken from a mammary gland. Her cloning proved that a cloned organism could be produced from a mature cell from a specific body part. Contrary to popular belief, she was not the first animal to be cloned.

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical copy of a human. The term is generally used to refer to artificial human cloning, which is the reproduction of human cells and tissue. It does not refer to the natural conception and delivery of identical twins. The possibilities of human cloning have raised controversies. These ethical concerns have prompted several nations to pass laws regarding human cloning.

Przewalski's horse, also called the takhi, Mongolian wild horse or Dzungarian horse, is a rare and endangered horse originally native to the steppes of Central Asia. It is named after the Russian geographer and explorer Nikolay Przhevalsky. Once extinct in the wild, since the 1990s it has been reintroduced to its native habitat in Mongolia in the Khustain Nuruu National Park, Takhin Tal Nature Reserve, and Khomiin Tal, as well as several other locales in Central Asia and Eastern Europe.

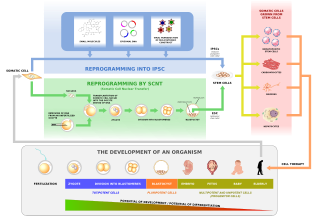

In genetics and developmental biology, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) is a laboratory strategy for creating a viable embryo from a body cell and an egg cell. The technique consists of taking a denucleated oocyte and implanting a donor nucleus from a somatic (body) cell. It is used in both therapeutic and reproductive cloning. In 1996, Dolly the sheep became famous for being the first successful case of the reproductive cloning of a mammal. In January 2018, a team of scientists in Shanghai announced the successful cloning of two female crab-eating macaques from foetal nuclei.

Commercial animal cloning is the cloning of animals for commercial purposes, including animal husbandry, medical research, competition camels and horses, pet cloning, and restoring populations of endangered and extinct animals. The practice was first demonstrated in 1996 with Dolly the sheep.

Nuclear transfer is a form of cloning. The step involves removing the DNA from an oocyte, and injecting the nucleus which contains the DNA to be cloned. In rare instances, the newly constructed cell will divide normally, replicating the new DNA while remaining in a pluripotent state. If the cloned cells are placed in the uterus of a female mammal, a cloned organism develops to term in rare instances. This is how Dolly the Sheep and many other species were cloned. Cows are commonly cloned to select those that have the best milk production. On 24 January 2018, two monkey clones were reported to have been created with the technique for the first time.

Hwang Woo-suk is a South Korean veterinarian and researcher. He was a professor of theriogenology and biotechnology at Seoul National University until he was dismissed on March 20, 2006. He was considered a pioneering expert in stem cell research and even called the "Pride of Korea". However, he became infamous around November 2005 for fabricating a series of stem cell experiments that were published in high-profile journals, the case known as the Hwang affair.

In bioethics, the ethics of cloning concerns the ethical positions on the practice and possibilities of cloning, especially of humans. While many of these views are religious in origin, some of the questions raised are faced by secular perspectives as well. Perspectives on human cloning are theoretical, as human therapeutic and reproductive cloning are not commercially used; animals are currently cloned in laboratories and in livestock production.

A frozen zoo is a storage facility in which genetic materials taken from animals are stored at very low temperatures (−196 °C) in tanks of liquid nitrogen. Material preserved in this way can be stored indefinitely and used for artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization, embryo transfer, and cloning. There are a few frozen zoos across the world that implement this technology for conservation efforts. Several different species have been introduced to this technology, including the Pyrenean ibex, Black-footed ferret, and potentially the white rhinoceros.

Keith Henry Stockman Campbell was a British biologist who was a member of the team at Roslin Institute that in 1996 first cloned a mammal, a Finnish Dorset lamb named Dolly, from fully differentiated adult mammary cells. He was Professor of Animal Development at the University of Nottingham. In 2008, he received the Shaw Prize for Medicine and Life Sciences jointly with Ian Wilmut and Shinya Yamanaka for "their works on the cell differentiation in mammals".

Interspecific pregnancy is the pregnancy involving an embryo or fetus belonging to another species than the carrier. Strictly, it excludes the situation where the fetus is a hybrid of the carrier and another species, thereby excluding the possibility that the carrier is the biological mother of the offspring. Strictly, interspecific pregnancy is also distinguished from endoparasitism, where parasite offspring grow inside the organism of another species, not necessarily in the womb.

The revival of the woolly mammoth is a proposed hypothetical that frozen soft-tissue remains and DNA from extinct woolly mammoths could be a means of regenerating the species. Several methods have been proposed to achieve this goal, including cloning, artificial insemination, and genome editing. Whether or not it is ethical to create a live mammoth is debated.

Noori was a female pashmina goat, the first pashmina goat to be cloned using the process of nuclear transfer. Born on 9 March 2012, she was kept at the place of her birth, at the Faculty of Veterinary Sciences and Animal Husbandry, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir, Shuhama, Srinagar in the Indian territory of Jammu and Kashmir.

The Pyrenean ibex, Aragonese and Spanish common name bucardo, Basque common name bukardo, Catalan common name herc and French common name bouquetin, was one of the four subspecies of the Iberian ibex or Iberian wild goat, a species endemic to the Pyrenees. Pyrenean ibex were most common in the Cantabrian Mountains, Southern France, and the northern Pyrenees. This species was common during the Holocene and Upper Pleistocene, during which their morphology, primarily some skulls, of the Pyrenean ibex was found to be larger than other Capra subspecies in southwestern Europe from the same time.

Morné de la Rey is a South African veterinary surgeon and embryo transfer specialist. In 2003, he was one of a team of scientists and veterinarians from his company Embryo Plus and the Danish Agriculture Institute to clone a cow, the first animal to be cloned in Africa. In 2016, he was one of a team to use in vitro fertilisation successfully for the first time in the Cape buffalo.

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua are a pair of identical crab-eating macaques that were created through somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), the same cloning technique that produced Dolly the sheep in 1996. They are the first cloned primates produced by this technique. Unlike previous attempts to clone monkeys, the donated nuclei came from fetal cells, not embryonic cells. The primates were born from two independent surrogate pregnancies at the Institute of Neuroscience of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai.

Mu-ming Poo is a Chinese neuroscientist. He is the Paul Licht Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley and the Founding Director of the Shanghai-based Institute of Neuroscience (ION) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. He was awarded the 2016 Gruber Prize in Neuroscience for his pioneering work on synaptic plasticity. At ION, Poo led a team of scientists that produced the world's first truly cloned primates, a pair of crab-eating macaques called Zhongzhong and Huahua in 2017, using somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT).

Revive & Restore is a nonprofit wildlife conservation organization focused on use of biotechnology in conservation. Headquartered in Sausalito, California, the organization's mission is to enhance biodiversity through the genetic rescue of endangered and extinct species. The organization was founded by Stewart Brand and his wife, Ryan Phelan.

Maya is a cloned female arctic wolf that was born from a beagle surrogate mother in China. She was born on June 10, 2022, and news of her birth was revealed to the public on September 19 of the same year at Harbin Polarland, in China's Heilongjiang Province, by the biotechnology company Sinogene.

References

- ↑ "Endangered animal clone produced". BBC News. 9 April 2003. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ Waters, Rob (9 June 2010). "Animal Cloning: The Next Phase". Bloomberg Business. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ "A black-footed ferret has been cloned, a first for a U.S. endangered species". Animals. 2021-02-18. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- ↑ "Ralph: The World's First Cloned Rat". Brighthub.com. 28 October 2008. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ "Scientist: First cloned camel born in Dubai". The Associated Press. April 14, 2009. Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ↑ "World's 1st cloned camel born in Dubai". Kuwait News Agency. April 14, 2009. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ↑ Mann, Charles C. (January 1, 2003). "The First Cloning Superpower". Wired.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ↑ Braun, David (February 14, 2002). "Scientists Successfully Clone Cat". National Geographic . Archived from the original on February 17, 2002. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ↑ "Few replicas as first cloned cat nears 10 | MNN - Mother Nature Network". Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ "Pet Cat Cloned for Christmas". BBC . December 23, 2004. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ↑ "China's First Cloned Kitten, Garlic". The Scientist . September 6, 2019. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- ↑ "Calf Cloned From Bovine Cell Line". Science. 277 (5328): 903b–903. 15 August 1997. doi:10.1126/science.277.5328.903b. S2CID 81020917.

- ↑ Cibelli, J. B.; Stice, S. L.; Golueke, P. J.; Kane, J. J. (1998). "Cloned transgenic calves produced from nonquiescent fetal fibroblasts". Science. 280 (5367): 1256–8. Bibcode:1998Sci...280.1256C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1022.1111 . doi:10.1126/science.280.5367.1256. PMID 9596577.

- ↑ "Researchers Show Clone from Aged Cow Can Produce Normal Calf". University of Connecticut web archive. June 11, 2001. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ↑ "Cloning gives second chance for bull". BBC News. September 3, 1999.

- ↑ Glass, Ira (November 23, 2019). "Reunited (And It Feels So Good)". This American Life. NPR.

- ↑ "86 Square a next step in science of genetics". Farmanddairy.com. 2000-12-28. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ "additional text". BBC News. 2000-12-19. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ Whitfield, John (23 November 2001) Cloned cows in the pink Nature, retrieved 5 February 2014

- 1 2 Lanza, R. P; Cibelli; Jose, B; Faber, D; Sweeney, R. W; Henderson, B; Nevala, W; West, M. D; Wettstein, P. J (2011). "Cloned cattle can be healthy and normal". Science. 294 (5548): 1893–1894. doi:10.1126/science.1063440. PMID 11729307. S2CID 26751726.

- ↑ Melgares, Pat (May 21, 2001). "K-State's First Cloned Calf May Provide More Clues For Improving the Technology". Kansas State University. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ "Embrapa wants to fecundate Vitória, the cloned heifer". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ↑ (6 August 002) Pampa Was Born Argentina Xplora, retrieved 29 January 2014

- ↑ Tübitak Mam Gmbe – F.K. "turkhaygen.gov.tr". turkhaygen.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 2018-04-14. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ "Spain clones first fighting bull". BBC . 19 May 2010.

- ↑ "First Brazilian Brahman clone born February 2011". INT'L BRAHMAN NEWS. March 7, 2011. Archived from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ↑ Yu, M.; et al. (2016). "Cloning of the African indigenous cattle breed Kenyan Boran". Anim Genet. 47 (4): 510–511. doi:10.1111/age.12441. PMC 5074306 . PMID 27109292.

- ↑ Gestión, Redacción (29 July 2016). "Nació el primer clon hecho en el Perú: la ternera Alma". gestion.pe. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ Baer, Drake (8 September 2015). "This Korean lab has nearly perfected dog cloning, and that's just the start". Business Insider UK. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ "White-tailed deer joins the clone parade – Health – Cloning". NBC News. 2003-12-22. Archived from the original on September 5, 2016. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ Mott, Maryann (3 August 2005). "Dog Cloned by South Korean Scientists". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on August 4, 2005. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ Bender, Kelli (2017-06-27). "You Look Familiar! Cloned Puppy Meets Her 'Mom' For the First Time". People. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- 1 2 "British couple celebrate after the birth of first cloned puppy of its kind". The Guardian . 26 December 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ "China begins training first cloned police dog". CNN. 2019-03-22. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- ↑ Wang, Serenitie; Rivers, Matt; Wang, Shunhe (27 December 2017). "Chinese firm clones gene-edited dog". CNN . Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ "China clones first gene-edited dog, sentencing him to possible early death". Fox News . 28 December 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ "Argentina Just Elected an Eccentric Populist Who Seeks Counsel From His Cloned Dogs". 20 November 2023.

- ↑ Gurdon JB; Elsdale TR; Fischberg M. (1958-07-05). "Sexually mature individuals of Xenopus laevis from the transplantation of single somatic nuclei". Nature. 182 (4627): 64–5. Bibcode:1958Natur.182...64G. doi:10.1038/182064a0. PMID 13566187. S2CID 4254765.

- ↑ Robert Briggs & Thomas J. King (May 1952). "Transplantation of Living Nuclei From Blastula Cells into Enucleated Frogs' Eggs". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 38 (5): 455–463. Bibcode:1952PNAS...38..455B. doi: 10.1073/pnas.38.5.455 . PMC 1063586 . PMID 16589125.

- ↑ "Cloning of flies is latest buzz". BBC News. 4 November 2004. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ Advanced Cell Technology, Inc. (1 December 2001). "Press Release – First cloned endangered animal was born at 7:30 PM on Monday, 8 January 2001". Archived from the original on 2008-05-31. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ↑ Keith Smith - BoerGoats.com (2001-03-29). "Megan". Boergoats.com. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ Northwest A & F University Biotechnology Research Institute. "Untitled Document".

- ↑ "Iranian Scientists Clone Goat". CBS News. Associated Press. 16 April 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ "Noori is world's first pashmina goat clone". Hindustan Times. 2012-03-16. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ Shaoni Bhattacharya (August 6, 2003). "World's First Cloned Horse is Born" . Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ↑ "Brown, Liz. "Scamper Clone Offered for Commercial Breeding" The Horse, online edition, November 15, 2008". Thehorse.com. 2008-11-15. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ "Clone of top jumper Gem Twist born". horsetalk.co.nz. September 17, 2008.

- ↑ Andrés Gambini; Javier Jarazo; Ramiro Olivera; Daniel F. Salamone (2012). "Equine Cloning: In Vitro and In Vivo Development of Aggregated Embryos". Biol Reprod. 87 (1): 15, 1–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.098855 . hdl: 11336/16296 . PMID 22553223.

- ↑ Cohen, Haley (31 July 2015). "How Champion-Pony Clones Have Transformed the Game of Polo". VFNews. Vanity Fair. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ Alexander, Harriet (8 December 2014). "Argentina's polo star Adolfo Cambiaso – the greatest sportsman you've never heard of?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ Ryan Bell (10 December 2013). "Game of Clones". Outside Online.

- ↑ Six cloned horses help rider win prestigious polo match – Jon Cohen, Science Magazine, 13 December 2016

- ↑ "Przewalski's Horse Project | Revive & Restore" . Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- ↑ "Cloned horse raises hopes for equestrian sports in China". 12 January 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ↑ Tuff, Kika. "Przewalski's Foal Offers Further Hope for Conservation Cloning" . Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- ↑ "THE PRZEWALSKI'S HORSE PROJECT" . Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ↑ Chaĭlakhian LM, Veprintsev BN, Sviridova TA (1987). "Electrostimulated cell fusion in cell engineering". Biofizika. 32 (5): viii–xi. PMID 3318941.

- ↑ Nowak, Rachel (3 November 2008) Cloning 'resurrects' long-dead mice The New Scientist, Retrieved 13 April 2014

- ↑ "Scientists 'clone' monkey, BBC News". 14 January 2000.

- ↑ "Cloned monkey stem cells produced". Nature News. 22 November 2007.

- ↑ "Meet Retro — the first rhesus monkey cloned using a new scientific method - CBS News". 17 January 2024.

- ↑ Liu, Zhen; et al. (24 January 2018). "Cloning of Macaque Monkeys by Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer". Cell . 172 (4): 881–887.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.020 . PMID 29395327.

- ↑ Briggs, Helen (24 January 2018). "First monkey clones created in Chinese laboratory". BBC News . Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "Scientists Successfully Clone Monkeys; Are Humans Up Next?". The New York Times . Associated Press. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "Chinese Scientists Clone Monkeys Using Method That Created Dolly The Sheep". NPR. January 24, 2018.

- ↑ Science China Press (23 January 2019). "Gene-edited disease monkeys cloned in China". EurekAlert! . Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ↑ Mandelbaum, Ryan F. (23 January 2019). "China's Latest Cloned-Monkey Experiment Is an Ethical Mess". Gizmodo . Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ↑ "Scientists Clone First Endangered Species: a Wild Sheep". News.nationalgeographic.com. 2010-10-28. Archived from the original on November 2, 2001. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ Deghan, Saeed Kamali (5 August 2015). "Scientists in Iran clone endangered mouflon – born to domestic sheep". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ Black, Richard (May 29, 2003). "Cloning first for horse family". BBC .

- ↑ McManus, Phil; Albrecht, Glenn; Graham, Raewyn (31 August 2012). The Global Horseracing Industry: Social, Economic, Environmental and Ethical Perspectives. Routledge. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-415-67731-8.

- ↑ "Pigs cloned for organs down at the 'pharm'". The Guardian. London. March 14, 2000.

- ↑ "Research progress: Pig cloning for organs". CNN. January 3, 2002. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012.

- ↑ Shukman, David (14 January 2014) China cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved 14 January 2014

- ↑ J. Folch; J. Cocero; M. J. Chesne; P. Alabart; J. K. Dominguez; V. Congnie; Y. Roche; A. Fernández-Árias; A. Marti; J. I. Sánchez; P. Echegoyen; E. Beckers; J. F. Sánchez; A. Bonastre; X. Vignon (2009). "First birth of an animal from an extinct subspecies (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) by cloning". Theriogenology. 71 (6): 1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2008.11.005 . PMID 19167744.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl. "Bringing Them Back To Life". Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ↑ Challah-Jacques, M.; Chesne, P.; Renard, J. P. (2003). "Production of Cloned Rabbits by Somatic Nuclear Transfer". Cloning and Stem Cells. 5 (4): 295–299. doi:10.1089/153623003772032808. PMID 14733748.

- ↑ First cloned rabbit, Stice L, Steven Ph.D. "Unlocking the Secrets of Science" (PDF). University of Georgia. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-01-26. Retrieved 2017-07-06.

- ↑ Bartlett, Zane, "Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer in Mammals (1938–2013)". Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2014-11-04). ISSN 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/8231.

- ↑ "Dolly the Sheep". University of Edinburgh, Roslin Institute. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ↑ Sheikhi, Marjohn (30 September 2015). "Birth anniversary of Royana; Iran's 1st cloned sheep". Mehr News Agency. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- ↑ "Türkiye´nin ilk kopya koyunu doğdu – BİLİM-TEK Haberleri". Haber7.com. 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ "Türkiye´nin 2. kopya koyunu Zarife – BİLİM-TEK Haberleri". Haber7.com. 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ "India clones world's first buffalo". The Times of India . Archived from the original on 2011-08-11.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "First cloned buffalo dies of heart problem: NDRI scientists". The Times of India . Archived from the original on 2014-02-02.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "CIRB becomes India's second centre to produce a cloned buffalo". dnaindia.com. 10 January 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ "First cloned buffalo born". China View. 21 March 2005. Archived from the original on March 21, 2005. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ↑ "Not Extinct Yet: Snuwolf and Snuwolffy". 26 March 2007.

- ↑ "World's first cloned wolf dies". Phys.Org. 1 September 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ↑ Yeung, Jessie (2022-09-21). "Chinese researchers clone an Arctic wolf in 'landmark' conservation project". CNN. Retrieved 2022-09-30.