The Goidelic or Gaelic languages form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the related Brittonic languages.

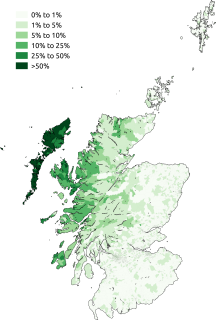

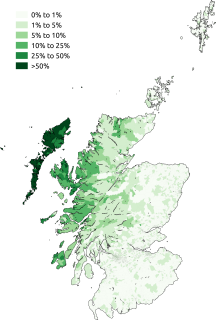

Scottish Gaelic, also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as both Irish and Manx, developed out of Old Irish. It became a distinct spoken language sometime in the 13th century in the Middle Irish period, although a common literary language was shared by the Gaels of both Ireland and Scotland until well into the 17th century. Most of modern Scotland was once Gaelic-speaking, as evidenced especially by Gaelic-language place names.

The Highlands is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands. The term is also used for the area north and west of the Highland Boundary Fault, although the exact boundaries are not clearly defined, particularly to the east. The Great Glen divides the Grampian Mountains to the southeast from the Northwest Highlands. The Scottish Gaelic name of A' Ghàidhealtachd literally means "the place of the Gaels" and traditionally, from a Gaelic-speaking point of view, includes both the Western Isles and the Highlands.

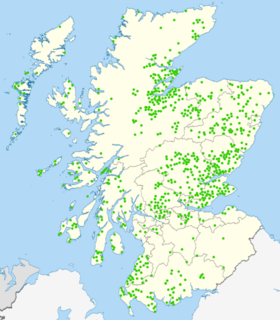

A Scottish clan is a kinship group among the Scottish people. Clans give a sense of shared identity and descent to members, and in modern times have an official structure recognised by the Court of the Lord Lyon, which regulates Scottish heraldry and coats of arms. Most clans have their own tartan patterns, usually dating from the 19th century, which members may incorporate into kilts or other clothing.

The Ulster Scots, also called Ulster Scots people or Scotch-Irish (Scotch-Airisch), are an ethnic group in Ireland, who speak an Ulster Scots dialect of the Scots language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history, culture and ancestry. As an ethnicity, they diverged from largely the same ancestors as those of modern English people, and Lowland Scots people, native to Northern England, and Lowland Scotland, respectively.

The Plantation of Ulster was the organised colonisation (plantation) of Ulster – a province of Ireland – by people from Great Britain during the reign of King James I. Most of the settlers came from southern Scotland and northern England; their culture differed from that of the native Irish. Small privately funded plantations by wealthy landowners began in 1606, while the official plantation began in 1609. Most of the colonised land had been confiscated from the native Gaelic chiefs, several of whom had fled Ireland for mainland Europe in 1607 following the Nine Years' War against English rule. The official plantation comprised an estimated half a million acres (2,000 km2) of arable land in counties Armagh, Cavan, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Donegal, and Londonderry. Land in counties Antrim, Down, and Monaghan was privately colonised with the king's support.

Scotch-IrishAmericans are American descendants of Ulster Protestants who emigrated from Ulster in northern Ireland to America during the 18th and 19th centuries, whose ancestors had originally migrated to Ireland mainly from the Scottish Lowlands and Northern England in the 17th century. In the 2017 American Community Survey, 5.39 million reported Scottish ancestry, an additional 3 million identified more specifically with Scotch-Irish ancestry, and many people who claim "American ancestry" may actually be of Scotch-Irish ancestry.

Scottish mythology is the collection of myths that have emerged throughout the history of Scotland, sometimes being elaborated upon by successive generations, and at other times being rejected and replaced by other explanatory narratives.

Scottish Americans or Scots Americans are Americans whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in Scotland. Scottish Americans are closely related to Scotch-Irish Americans, descendants of Ulster Scots, and communities emphasize and celebrate a common heritage. The majority of Scotch-Irish Americans originally came from Lowland Scotland and Northern England before migrating to the province of Ulster in Ireland and thence, beginning about five generations later, to North America in large numbers during the eighteenth century. Today, the number of Scottish Americans is believed to be around 25 million, and celebrations of ‘Scottishness’ can be seen through major Tartan Day parades and Burns Night celebrations.

The Scottish diaspora consists of Scottish people who emigrated from Scotland and their descendants. The diaspora is concentrated in countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, England, New Zealand, Ireland and to a lesser extent Argentina, Chile and Brazil.

The origins of the Kingdom of Alba pertain to the origins of the Kingdom of Alba, or the Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland, either as a mythological event or a historical process, during the Early Middle Ages.

The history of the modern kilt stretches back to at least the end of the 16th century. The kilt first appeared as the belted plaid or great kilt, a full-length garment whose upper half could be worn as a cloak draped over the shoulder, or brought up over the head as a hood. The small kilt or walking kilt did not develop until the late17th or early 18th century, and is essentially the bottom half of the great kilt.

The languages of Scotland are the languages spoken or once spoken in Scotland. Each of the numerous languages spoken in Scotland during its recorded linguistic history falls into either the Germanic or Celtic language families. The classification of the Pictish language was once controversial, but it is now generally considered a Celtic language. Today, the main language spoken in Scotland is English, while Scots and Scottish Gaelic are minority languages. The dialect of English spoken in Scotland is referred to as Scottish English.

Scottish Canadians are people of Scottish descent or heritage living in Canada. As the third-largest ethnic group in Canada and amongst the first Europeans to settle in the country, Scottish people have made a large impact on Canadian culture since colonial times. According to the 2016 Census of Canada, the number of Canadians claiming full or partial Scottish descent is 4,799,010, or 13.93% of the nation's total population. However, some demographers have estimated that the number of Scottish Canadians could be up to 25% of the Canadian population. Prince Edward Island has the highest population of Scottish descendants at 41%.

The Gaels are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic.

Sean, also spelled Seán or Séan in Irish English, is a male given name of Irish origin. It comes from the Irish versions of the Biblical Hebrew name Yohanan, Seán and Séan, rendered John in English and Johannes/Johann/Johan in other Germanic languages. The Norman French Jehan is another version.

The Scots are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically, they emerged in the early Middle Ages from an amalgamation of two Celtic-speaking peoples, the Picts and Gaels, who founded the Kingdom of Scotland in the 9th century. In the following two centuries, the Celtic-speaking Cumbrians of Strathclyde and the Germanic-speaking Angles of north Northumbria became part of Scotland. In the High Middle Ages, during the 12th-century Davidian Revolution, small numbers of Norman nobles migrated to the Lowlands. In the 13th century, the Norse-Gaels of the Western Isles became part of Scotland, followed by the Norse of the Northern Isles in the 15th century.

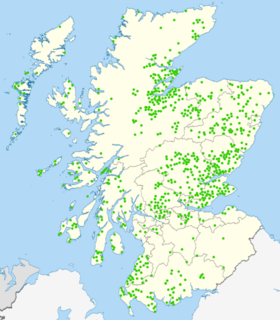

Scottish Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to Scotland. A member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages, Scottish Gaelic, like Modern Irish and Manx, developed out of Middle Irish. Most of modern Scotland was once Gaelic-speaking, as evidenced especially by Gaelic-language placenames.

19th-century Anglo-Saxonism, or racial Anglo-Saxonism, was a racial belief system developed by British and American intellectuals, politicians and academics in the 19th century. Racialized Anglo-Saxonism contained both competing and intersecting doctrines, such as Victorian-era Old Northernism and the Teutonic germ theory which it relied upon in appropriating Germanic cultural and racial origins for the Anglo-Saxon "race".

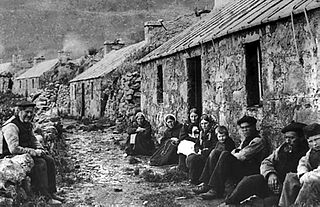

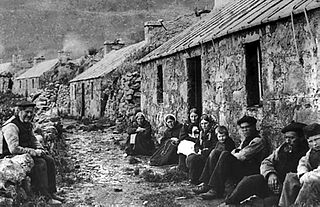

Scots Gaelic people, also known as Scottish Gaelic people, Scots Gaels, Highland Gaels, Highland Scots or Highlanders, are a Gaelic ethnic group native to Scotland who speak the Scottish Gaelic language, a Goidelic language, and share a common history, culture and ancestry.