Placoderms are vertebrate animals of the class Placodermi, an extinct group of prehistoric fish known from Paleozoic fossils during the Silurian and the Devonian periods. While their endoskeletons are mainly cartilaginous, their head and thorax were covered by articulated armoured plates, and the rest of the body was scaled or naked depending on the species.

Bothriolepis was a widespread, abundant and diverse genus of antiarch placoderms that lived during the Middle to Late Devonian period of the Paleozoic Era. Historically, Bothriolepis resided in an array of paleo-environments spread across every paleocontinent, including near shore marine and freshwater settings. Most species of Bothriolepis were characterized as relatively small, benthic, freshwater detritivores, averaging around 30 centimetres (12 in) in length. However, the largest species, B. rex, had an estimated bodylength of 170 centimetres (67 in). Although expansive with over 60 species found worldwide, comparatively Bothriolepis is not unusually more diverse than most modern bottom dwelling species around today.

Drepanaspis is an extinct genus of heterostracan armoured jawless fish from the Early Devonian. Drepanaspis are assumed to have lived primarily in marine environments and is most commonly characterized by their ray-like, heavily armoured bodies, along with their lack of paired fins and jaws.

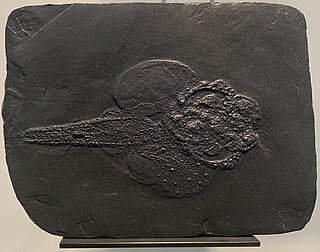

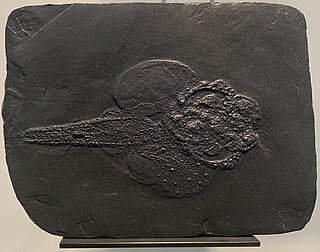

Groenlandaspis is an extinct genus of arthrodire from the Late Devonian. Fossils of the different species are found in late Devonian strata in all continents except eastern Asia. The generic name commemorates the fact that the first specimens of the type species were found in Greenland.

Petalichthyida is an extinct order of small, flattened placoderm fish. They are typified by their splayed pectoral fins, exaggerated lateral spines, flattened bodies, and numerous tubercles that decorated all of the plates and scales of their armor. They reached a peak in diversity during the Early Devonian and were found throughout the world, particularly in Europe, North America, Asia, South America, and Australia. The petalichthids Lunaspis and Wijdeaspis are among the best known. The earliest and most primitive known petalichthyid is Diandongpetalichthys, which is from earliest Devonian-aged strata of Yunnan. The presence of Diandongpetalichthys, along with other primitive petalichthyids including Neopetalichthys and Quasipetalichthys, and more advanced petalichthyids, suggest that the order may have arisen in China, possibly during the late Silurian.

Rhenanida is an order of scaly placoderms. Unlike most other placoderms, the rhenanids' armor was made up of a mosaic of unfused scales and tubercles. The patterns and components of this "mosaic" correspond to the plates of armor in other, more advanced placoderms, suggesting that the ancestral placoderm had armor made of unfused components, as well.

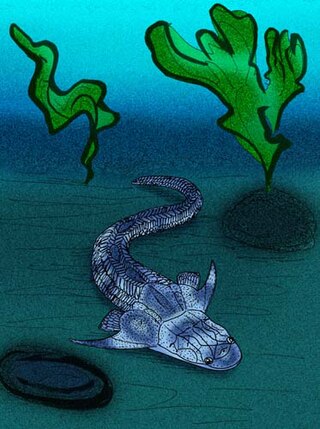

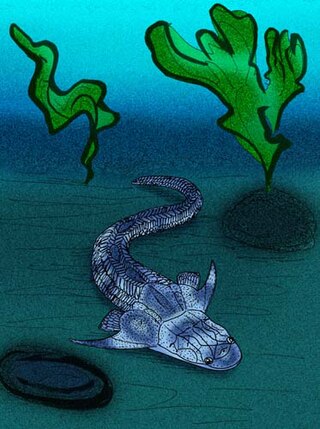

Gemuendina stuertzi is a placoderm of the order Rhenanida, of the seas of Early Devonian Germany. In life, Gemuendina resembled a scaly ray with an upturned head, or a large-finned stargazer. G. stuertzi is often invoked as an example of convergent evolution- with its flat body and huge, wing-like pectoral fins it has a strong, albeit superficial similarity to rays. Unlike rays, however, both Gemuendina`s eyes and nostrils were placed atop the head, facing upward. Furthermore, G. stuertzi's upturned mouth would have enabled it to suction prey that swam overhead, rather than swallow sediment or suction prey out of the substrate like modern rays.

Brindabellaspis stensioi is a placoderm with a flat, platypus-like snout from the Early Devonian of the Taemas-Wee Jasper reef in Australia. When it was first discovered in 1980, it was originally regarded as a Weejasperaspid acanthothoracid due to anatomical similarities with the other species found at the reef.

Onychodus is a genus of prehistoric lobe-finned fish which lived during the Devonian Period. It is one of the best known of the group of onychodontiform fishes. Scattered fossil teeth of Onychodus were first described from Ohio in 1857 by John Strong Newberry. Other species were found in Australia, England, Norway and Germany showing that it had a widespread range.

Eusthenodon is an extinct genus of tristichopterid tetrapodomorphs from the Late Devonian period, ranging between 383 and 359 million years ago. They are well known for being a cosmopolitan genus with remains being recovered from East Greenland, Australia, Central Russia, South Africa, Pennsylvania, and Belgium. Compared to the other closely related genera of the Tristichopteridae clade, Eusthenodon was one of the largest lobe-finned fishes and among the most derived tristichopterids alongside its close relatives Cabonnichthys and Mandageria.

Holonema is an extinct genus of relatively large, barrel-shaped arthrodire placoderms that were found in oceans throughout the world from the Mid to Late Devonian, when the last species perished in the Frasnian-Fammian extinction event. Most species of the genus are known from fragments of their armor, but the Gogo Reef species, H. westolli, is known from whole, articulated specimens.

Holdenius is an extinct genus of arthrodire placoderm fish which lived during the Late Devonian period.

Homostiidae is a family of flattened arthrodire placoderms from the Early to Middle Devonian. Fossils appear in various strata in Europe, Russia, Morocco, Australia, Canada and Greenland.

Diandongpetalichthys liaojiaoshanensis is an extinct petalichthyid placoderm from the Early Devonian of China.

Vukhuclepis lyhoaensis is an extinct, primitive antiarch placoderm. Specimens are of mostly complete thoracic armor from the Early Devonian Ly Hoa Formation in Vietnam. The armor is very similar to that of Yunnanolepis, but is distinguished by a unique pattern of raised ridges radiating from a point at the center of the dorsal shield of the thoracic armor. A similar, albeit more floral-looking pattern is seen in the Chinese Mizia. V. lyhaoensis' armor is further ornamented with small tubercles.

Brachydeirus is a genus of small to moderately large-sized arthrodire placoderms from the Late Devonian of Europe, restricted to the Kellwasserkalk Fauna of Bad Wildungen and Adorf.

Microbrachius is an extinct genus of tiny, advanced antiarch placoderms closely related to the bothriolepids. Specimens range in age from the Lower Devonian Late Emsian Stage to the Middle Devonian Upper Givetian Stage. They are characterized by having large heads with short thoracic armor of an average length of 2–4 cm. There are patterns of small, but noticeable tubercles on the armor, with the arrangement varying from species to species. Specimens of Microbrachius have been found in Scotland, Belarus, Estonia, and China.

Romundina is a small, heavily armored extinct genus of acanthothoracid placoderms which lived in shallow marine environments in the early Devonian (Lochkovian). The name Romundina honors Canadian geologist and paleontologist Dr. Rómundur (Raymond) Thorsteinsson of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Romundina are believed to have lived on Earth between 400 and 419 million years ago. The closest known relative to Romundina is the acanthothoracid Radotina. The type and only described species is R. stellina.

Qilinyu is a genus of early placoderm from the late Silurian of China. It contains a single species, Qilinyu rostrata, from the Xiaoxiang fauna of the Kuanti Formation. Along with its contemporary Entelognathus, Qilinyu is an unusual placoderm showing some traits more similar to bony fish, such as dermal jaw bones and lobe-like fins. It can be characterized by adaptations for a benthic lifestyle, with the mouth and nostrils on the underside of the head, similar to the unrelated antiarch placoderms. The shape of the skull has been described as "dolphin-like", with a domed cranium and a short projecting rostrum.

Kimbryanodus is a genus of extinct ptyctodontid placoderm fish from the Frasnian of Australia.These placoderms can be told apart from others due to the large eyes, crushing tooth plates, long bodies, reduced armor, and a superficial resemblance to holocephalid fish. The group is so far the only Placoderms known with sexually dimorphic features. The fossils occur as small three dimensional isolated plates. Because of these new specimens the Ptyctodontid grouping got a taxonomic classification, it found that the genus Rhamphodopsis to be the most basal taxa. They are divided by having the more basal taxa having a median dorsal spine, a simple spinal plate, and a simple V-shaped overlap of the anterior lateral and the anterior dorsolateral plates.