Otorhinolaryngology is a surgical subspecialty within medicine that deals with the surgical and medical management of conditions of the head and neck. Doctors who specialize in this area are called otorhinolaryngologists, otolaryngologists, head and neck surgeons, or ENT surgeons or physicians. Patients seek treatment from an otorhinolaryngologist for diseases of the ear, nose, throat, base of the skull, head, and neck. These commonly include functional diseases that affect the senses and activities of eating, drinking, speaking, breathing, swallowing, and hearing. In addition, ENT surgery encompasses the surgical management of cancers and benign tumors and reconstruction of the head and neck as well as plastic surgery of the face, scalp, and neck.

Sinusitis, also known as rhinosinusitis, is an inflammation of the mucous membranes that line the sinuses resulting in symptoms that may include production of thick nasal mucus, nasal congestion, facial congestion, facial pain, facial pressure, loss of smell, or fever.

Prosper Menière was a French medical doctor who first identified that the inner ear could be the source of a condition combining vertigo, hearing loss and tinnitus, which is now known as Ménière's disease.

Tinnitus is a condition when a person hears a ringing sound or a different variety of sound when no corresponding external sound is present and other people cannot hear it. Nearly everyone experiences faint "normal tinnitus" in a completely quiet room; but this is of concern only if it is bothersome, interferes with normal hearing, or is associated with other problems. The word tinnitus comes from the Latin tinnire, "to ring". In some people, it interferes with concentration, and can be associated with anxiety and depression.

Otitis media is a group of inflammatory diseases of the middle ear. One of the two main types is acute otitis media (AOM), an infection of rapid onset that usually presents with ear pain. In young children this may result in pulling at the ear, increased crying, and poor sleep. Decreased eating and a fever may also be present. The other main type is otitis media with effusion (OME), typically not associated with symptoms, although occasionally a feeling of fullness is described; it is defined as the presence of non-infectious fluid in the middle ear which may persist for weeks or months often after an episode of acute otitis media. Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) is middle ear inflammation that results in a perforated tympanic membrane with discharge from the ear for more than six weeks. It may be a complication of acute otitis media. Pain is rarely present. All three types of otitis media may be associated with hearing loss. If children with hearing loss due to OME do not learn sign language, it may affect their ability to learn.

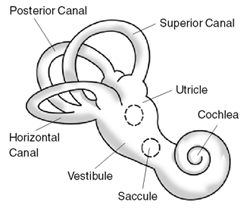

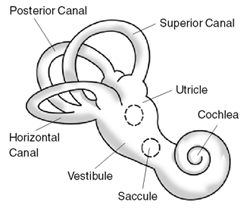

Labyrinthitis is inflammation of the labyrinth, a maze of fluid-filled channels in the inner ear. Vestibular neuritis is inflammation of the vestibular nerve. Both conditions involve inflammation of the inner ear. Labyrinths that house the vestibular system sense changes in the head's position or the head's motion. Inflammation of these inner ear parts results in a vertigo and also possible hearing loss or tinnitus. It can occur as a single attack, a series of attacks, or a persistent condition that diminishes over three to six weeks. It may be associated with nausea, vomiting, and eye nystagmus.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a disorder arising from a problem in the inner ear. Symptoms are repeated, brief periods of vertigo with movement, characterized by a spinning sensation upon changes in the position of the head. This can occur with turning in bed or changing position. Each episode of vertigo typically lasts less than one minute. Nausea is commonly associated. BPPV is one of the most common causes of vertigo.

Hyperacusis is an increased sensitivity to sound and a low tolerance for environmental noise. Definitions of hyperacusis can vary significantly; it often revolves around damage to or dysfunction of the stapes bone, stapedius muscle or tensor tympani (eardrum). It is often categorized into four subtypes: loudness, pain, annoyance, and fear. It can be a highly debilitating hearing disorder.

Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) is a form of habituation therapy designed to help people who experience tinnitus—a ringing, buzzing, hissing, or other sound heard when no external sound source is present. Two key components of TRT directly follow from the neurophysiological model of tinnitus: Directive counseling aims to help the sufferer reclassify tinnitus to a category of neutral signals, and sound therapy weakens tinnitus-related neuronal activity.

Betahistine, sold under the brand name Serc among others, is an anti-vertigo medication. It is commonly prescribed for balance disorders or to alleviate vertigo symptoms. It was first registered in Europe in 1970 for the treatment of Ménière's disease, but current evidence does not support its efficacy in treating it.

Vertigo is a condition in which a person has the sensation that they are moving, or that objects around them are moving, when they are not. Often it feels like a spinning or swaying movement. It may be associated with nausea, vomiting, perspiration, or difficulties walking. It is typically worse when the head is moved. Vertigo is the most common type of dizziness.

A neurectomy, or nerve resection is a neurosurgical procedure in which a peripheral nerve is cut or removed to alleviate neuropathic pain or permanently disable some function of a nerve. The nerve is not intended to grow back. For chronic pain it may be an alternative to a failed nerve decompression when the target nerve has no motor function and numbness is acceptable. Neurectomies have also been used to permanently block autonomic function, and special sensory function not related to pain.

Endolymphatic hydrops is a disorder of the inner ear. It consists of an excessive build-up of the endolymph fluid, which fills the hearing and balance structures of the inner ear. Endolymph fluid, which is partly regulated by the endolymph sac, flows through the inner ear and is critical to the function of all sensory cells in the inner ear. In addition to water, endolymph fluid contains salts such as sodium, potassium, chloride and other electrolytes. If the inner ear is damaged by disease or injury, the volume and composition of the endolymph fluid can change, causing the symptoms of endolymphatic hydrops.

The semicircular canal dehiscence (SCD) is a category of rare neurotological diseases/disorders affecting the inner ears, which gathers the superior SCD, lateral SCD and posterior SCD. These SCDs induce SCD syndromes (SCDSs), which define specific sets of hearing and balance symptoms. This entry mainly deals with the superior SCDS.

The Epley maneuver or repositioning maneuver is a maneuver used by medical professionals to treat one common cause of vertigo, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) of the posterior or anterior canals of the ear. The maneuver works by allowing free-floating particles, displaced otoconia, from the affected semicircular canal to be relocated by using gravity, back into the utricle, where they can no longer stimulate the cupula, therefore relieving the patient of bothersome vertigo. The maneuver was developed by the physician John M. Epley, and was first described in 1980.

Vestibular migraine (VM) is vertigo with migraine, either as a symptom of migraine or as a related neurological disorder.

An endolymphatic sac tumor (ELST) is a very uncommon papillary epithelial neoplasm arising within the endolymphatic sac or endolymphatic duct. This tumor shows a very high association with Von Hippel–Lindau syndrome (VHL).

Migraine may be treated either prophylactically (preventive) or abortively (rescue) for acute attacks. Migraine is a complex condition; there are various preventive treatments which disrupt different links in the chain of events that occur during a migraine attack. Rescue treatments also target and disrupt different processes occurring during migraine.

A labyrinthectomy is a procedure used to decrease the function of the labyrinth of the inner ear. This can be done surgically or chemically. It may be done to treat Ménière's disease.

Cochlear hydrops is a condition of the inner ear involving a pathological increase of fluid affecting the cochlea. This results in swelling that can lead to hearing loss or changes in hearing perception. It is a form of endolymphatic hydrops and related to Ménière's disease. Cochlear hydrops refers to a case of inner-ear hydrops that only involves auditory symptoms and does not cause vestibular issues.