Background

Window glassmaking in the 1880s

Glass is made by starting with a batch of ingredients (mostly sand), melting it, forming the glass product, and gradually cooling it. [Note 1] The batch is placed inside a pot or tank that is heated by a furnace to roughly 3090 °F (1700 °C). [1] During the 1880s, window glass was made using the hand–blown cylinder glass method. [3] A crew led by a glassblower started the process of shaping the glass. A gatherer removed a glob of molten glass (called a gob) from the furnace using a blowpipe. [4] The blowpipe, with its gob, was then passed to a glassblower, who would blow into the pipe to start the creation of a hollow cylinder. The glassblower would enlarge the cylinder, sometimes with the assistance of a wooden mold. [3] Periodically the glassblower would reheat the cylinder to keep it elastic. The reheating was done at a section of the furnace called the glory hole, which was a small hole in the side of the furnace that was often at right angles to the main gathering hole. [5] A typical cylinder was up to five feet (1.5 m) long. [6] The cylinder was cooled and then cut at both ends (the "caps") by a craftsman called a cutter. [6] The cylinder, now a tube, was then cut lengthwise to prepare it for flattening. [7]

Glass products must be cooled gradually (annealed), or else they can become brittle and possibly break. [8] A long conveyor oven used for annealing is called a lehr. [9] In the case of window glass, a combination flattening oven and lehr could be used. [10] The glass tube was placed in the oven with the slit side up. Workers known as flatteners make sure the reheated cylinder unfolds into a flat sheet. [7] After the flat glass has moved from the hot end of the oven to the cool end, which can take hours, it is inspected, cut to the desired size, and packed. [11] The size of each piece of window glass varied, but was limited by the size of the cylinder. Statistics for unpolished window glass imported into the United States in 1880 show that about half of the tonnage consisted of glass above 10 inches (25 cm) by 15 inches (38 cm) in size and below 24 inches (61 cm) by 30 inches (76 cm). [12]

Most glass factories had a summer stop where the production was shut down for about six weeks. [13] This was done because the summer heat combined with the heat of the furnace to make the work environment almost unbearable for workers in the hot end (near molten glass). The summer stop also allowed time to perform maintenance on the facility without disrupting the production process. [13] Window glass workers spent more time adjacent to furnaces and ovens because they reheated their product, so some companies had summer stops that lasted from the beginning of May until the end of August. [6]

Because most glass plants melted their batch in a pot during the 1880s, the plant's number of pots was often used to describe a plant's capacity. The ceramic pots were located inside the furnace, and contained molten glass created by melting the batch of ingredients. [14] Tank furnaces, which were less common than pots in the 1880s, were essentially large brick pot furnaces with multiple workstations. A tank furnace is more efficient than a pot furnace, but more costly to build. [15] One of the major expenses for the glass factories is fuel for the furnace. [16] Wood and coal had long been used as fuel for glassmaking. An alternative fuel, natural gas, became a desirable fuel for making glass in the late 19th century because it is clean, gives a uniform heat, is easier to control, and melts the batch of ingredients faster. [17]

Belgian glassmakers

During the 1880s, Belgium was known for its window glass manufacturing, and about two thirds of the window glass it made was exported. [18] The window glass workers were skilled as glassblowers, gatherers, flatteners, and cutters—and these skills were learned in long apprenticeships. [19] Many of its window glass works, over 130 operating furnaces, were located in Charleroi, which is not far from the border with France. [20] In 1886, approximately 30 percent of the Belgian glassworkers were unemployed because of strikes and a recession. [21]

In America, natural gas was discovered in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana during the 1880s and 1890s—causing economic "gas booms". Politicians and businessmen in these American communities took advantage of the newfound fuel source to entice manufacturers, including glass makers, to locate their plants near the low–cost fuel sources. The glass manufacturers also needed skilled labor for their plants. [22] Thus, the American window glass plants needed skilled labor, and a good supply of skilled labor was available in Belgium. The Belgian window glass workers that came to America around this time made their product using the hand–blown cylinder method. [19] [Note 2] Among the Belgian glass workers that came to America was Leopold Mambourg (1860–1929), who started his American career at Pittsburg Plate Glass Company. [25]

Ohio glass industry

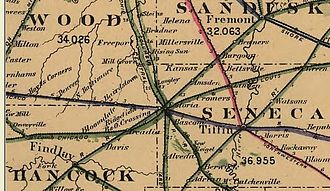

In the 1870s Ohio had a glass industry located principally in the eastern portion of the state, especially in coal-rich Belmont County. The Belmont County community of Bellaire, located on the Ohio side of the Ohio River across from Wheeling, West Virginia, was known as "Glass City" from 1870 to 1885. [26] In early 1886, a major discovery of natural gas (the Karg Well) occurred in northwest Ohio near the small village of Findlay. [27] Communities in northwestern Ohio began using low-cost natural gas along with free land and cash to entice manufacturing companies (especially glass makers) to start operations in their towns. [28] The enticement efforts were successful, and at least 70 glass factories existed in northwest Ohio between 1886 and the early 20th century. [29]

The city of Fostoria, already blessed with multiple railroad lines, was close enough to the natural gas that it was able to use a pipeline to make natural gas available to businesses. [30] Eventually, Fostoria had 13 different glass companies at various times between 1887 and 1920. [31] [Note 3] The gas boom in northwestern Ohio enabled the state to improve its national ranking as a manufacturer of glass (based on value of product) from 4th in 1880 to 2nd in 1890. [34] However, northwestern Ohio had serious problems with its gas supply by 1891, and the glass industry had over–expanded. [35] [Note 4] Some local companies, such as Fostoria Glass Company, decided to move elsewhere to be near better fuel supplies. [36]