The Ben Youssef Madrasa is an Islamic madrasa (college) in Marrakesh, Morocco. Functioning today as a historical site, the Ben Youssef Madrasa was the largest Islamic college in the Maghreb at its height. The madrasa is named after the adjacent Ben Youssef Mosque built by the Almoravid Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf in the early 12th century, and was commissioned by the Saadian sultan Abdallah al-Ghalib in the 16th century.

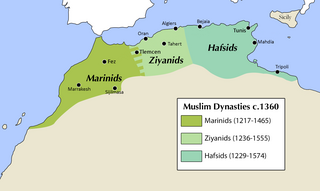

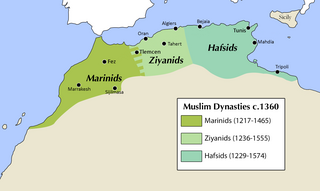

The Marinid Sultanate was a Berber Muslim empire from the mid-13th to the 15th century which controlled present-day Morocco and, intermittently, other parts of North Africa and of the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain) around Gibraltar. It was named after the Banu Marin, a Zenata Berber tribe. The sultanate was ruled by the Marinid dynasty, founded by Abd al-Haqq I.

Moroccan architecture reflects Morocco's diverse geography and long history, marked by successive waves of settlers through both migration and military conquest. This architectural heritage includes ancient Roman sites, historic Islamic architecture, local vernacular architecture, 20th-century French colonial architecture, and modern architecture.

Zellij is a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled tile pieces. The pieces were typically of different colours and fitted together to form various patterns on the basis of tessellations, most notably elaborate Islamic geometric motifs such as radiating star patterns. This form of Islamic art is one of the main characteristics of architecture in the western Islamic world. It is found in the architecture of Morocco, the architecture of Algeria, early Islamic sites in Tunisia, and in the historic monuments of al-Andalus. From the 14th century onwards, zellij became a standard decorative element along lower walls, in fountains and pools, on minarets, and for the paving of floors.

The Bou Inania Madrasa or Bu 'Inaniya Madrasa is a madrasa in Fes, Morocco, built in 1350–55 CE by Abu Inan Faris. It is the only madrasa in Morocco which also functioned as a congregational mosque. It is widely acknowledged as a high point of Marinid architecture and of historic Moroccan architecture generally.

The Zawiya of Moulay Idris II is a zawiya in Fez, Morocco. It contains the tomb of Idris II, who ruled Morocco from 807 to 828 and is considered the main founder of the city of Fez. It is located in the heart of Fes el-Bali, the UNESCO-listed old medina of Fez, and is considered one of the holiest shrines in Morocco. The current building experienced a major reconstruction under Moulay Ismail in the early 18th century which gave the sanctuary its overall current form, including the minaret and the mausoleum chamber with its large pyramidal roof.

The Al-Attarine Madrasa or Medersa al-Attarine is a madrasa in Fes, Morocco, near the Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque. It was built by the Marinid sultan Uthman II Abu Said in 1323-5. The madrasa takes its name from the Souk al-Attarine, the spice and perfume market. It is considered one of the highest achievements of Marinid architecture due to its rich and harmonious decoration and its efficient use of limited space.

The Grand Mosque of Tangier is the historic main mosque of Tangier, Morocco, located in the city's old medina. While the design of the current mosque dates from the early 19th century during the Alaouite period, the site has been occupied by a succession of religious buildings since antiquity.

Funduq al-Najjarin is a historic funduq in Fes el Bali, the old medina quarter in the city of Fez, Morocco.

Sahrij Madrasa or Madrasa al-Sahrij is a madrasa in Fez, Morocco. The madrasa is located inside Fes el Bali, the old medina quarter of the city. The madrasa dates back to the 14th century during the golden age of Fez under Marinid rule. The madrasa is located near Al Andalus Mosque and is also connected to another, smaller, madrasa built at the same time, the Sba'iyyin Madrasa.

The Bab Guissa Mosque is a medieval mosque in northern Fes el-Bali, the old city of Fez, Morocco. It is located next to the city gate of the same name, and also features an adjoining madrasa.

The R'cif Mosque is a Friday mosque in Fes el-Bali, the old city (medina) of Fez, Morocco. It has one of the tallest minarets in the city and overlooks Place R'cif in the heart of the medina.

The Chrabliyine Mosque is a Marinid-era mosque in Fez, Morocco.

The architecture of Fez, Morocco, reflects the wider trends of Moroccan architecture dating from the city's foundation in the late 8th century and up to modern times. The old city (medina) of Fes, consisting of Fes el-Bali and Fes el-Jdid, is notable for being an exceptionally well-preserved medieval North African city and is classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A large number of historic monuments from different periods still exist in it today, including mosques, madrasas, synagogues, hammams (bathhouses), souqs (markets), funduqs (caravanserais), defensive walls, city gates, historic houses, and palaces.

Tala'a Kebira is one of the longest and most important streets in Fes el-Bali, the old city (medina) of Fes, Morocco. The street runs roughly east to west, starting near the Bab Bou Jeloud and Bab Mahrouk gates in the west and ending at the al-Attarine Madrasa in the east, near the Qarawiyyin Mosque. It constitutes one of the main souq streets in the old city and a number of important historic monuments are built along it.

The al-Hamra Mosque or Red Mosque is a Marinid-era mosque in Fes, Morocco. It is a local Friday mosque located on the Grande Rue of Fes el-Jdid, the palace-city founded by the Marinid rulers.

The Lalla Aouda Mosque or Mosque of Lalla 'Awda is a large historic mosque in Meknes, Morocco. It was originally the mosque of the Marinid kasbah (citadel) of the city, built in 1276, but was subsequently remodeled into the royal mosque of the Alaouite sultan Moulay Isma'il's imperial palace in the late 17th century.

Funduq Sagha is a historic funduq in Fes el Bali, the old medina quarter in the city of Fez, Morocco.

Hammam al-Mokhfiya is a historic hammam (bathhouse) in the medina of Fes, Morocco. It is located in the neighbourhood of the same name (al-Mokhfiya), south of Place R'cif. Based on its similarities in layout and decoration with other historic hammams in the region, it has been dated to the mid-14th century, during the reign of the Marinid sultan Abu Inan or slightly after. The hammam is richly decorated with carved stucco and carved wood in its changing room, as well as zellij tiling in its steam rooms. The hammam was part of the habous (endowment) of the Qarawiyyin Mosque.

The Maristan of Granada was a bimaristan (hospital) in Granada, Spain. It was built in the 14th century during the Nasrid period and demolished in the 19th century.