|

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

Milites were the trained regular footsoldiers of ancient Rome, and later a term used to describe "soldiers" in Medieval Europe.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

Milites were the trained regular footsoldiers of ancient Rome, and later a term used to describe "soldiers" in Medieval Europe.

These men were the non-specialist regular soldiers that made up the bulk of a legion's numbers. Alongside soldiering, they also performed guard duties, labour work, building and other non-combat roles, which increased their status in urban centers. [1] Milites would usually have to serve for several years before becoming eligible for training to become immunes and thus become specialists with better pay. [2] [3]

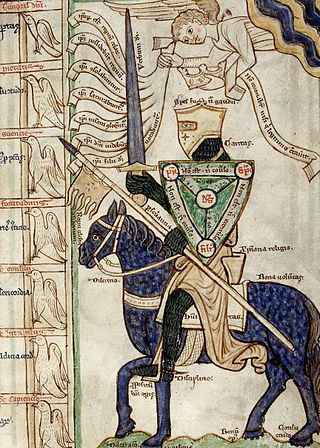

The Latin term eventually became synonymous with "soldier", a general term that, in Western Europe, became associated with the mounted knight, because they composed the professional military corps during the Early Medieval Era. [4] [5] [6] [7] The same term, however, was expanded to mean less distinguished infantry soldiers (milites pedites). [7] [8] During the 13th century the term referred to the mounted horsemen who lacked knight-status, but still had similar properties and obligations to the dubbed knights. [9]

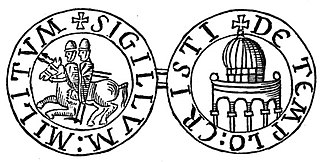

Other usages include the "Milites Templi," referring to the Knights Templar, or Milites Sancti Jacobi (Order of Santiago). [10] [11] [12]

From the Latin root, "Miles" derived words such as "Military" and "Militia".

Adhemarde Monteil was one of the principal figures of the First Crusade and was bishop of Puy-en-Velay from before 1087. He was the chosen representative of Pope Urban II for the expedition to the Holy Land. Remembered for his martial prowess, he led knights and men into battle and fought beside them, particularly at the Battle of Dorylaeum and Siege of Antioch. Adhemar is said to have carried the Holy Lance in the Crusaders’ desperate breakout at Antioch on 28 June 1098, in which superior Islamic forces under the atabeg Kerbogha were routed, securing the city for the Crusaders. He died in 1098 due to illness.

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a military order of the Catholic faith, and one of the wealthiest and most popular military orders in Western Christianity. They were founded c. 1119, headquartered on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and existed for nearly two centuries during the Middle Ages.

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ancient Greek hippeis (ἱππεῖς) and Roman equites.

Medieval warfare is the warfare of the Middle Ages. Technological, cultural, and social advancements had forced a severe transformation in the character of warfare from antiquity, changing military tactics and the role of cavalry and artillery. In terms of fortification, the Middle Ages saw the emergence of the castle in Europe, which then spread to the Holy Land.

Saracen was a term used both in Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Petraea and Arabia Deserta. The term's meaning evolved during its history of usage. During the Early Middle Ages, the term came to be associated with the tribes of Arabia.

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of various chivalric orders; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed by chivalrous social codes. The ideals of chivalry were popularized in medieval literature, particularly the literary cycles known as the Matter of France, relating to the legendary companions of Charlemagne and his men-at-arms, the paladins, and the Matter of Britain, informed by Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, written in the 1130s, which popularized the legend of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table.

The Battle of Hattin took place on 4 July 1187, between the Crusader states of the Levant and the forces of the Ayyubid sultan Saladin. It is also known as the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, due to the shape of the nearby extinct volcano of that name.

A warrior is a person specializing in combat or warfare, especially within the context of a tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracy, class, or caste.

A military order is a Christian religious society of knights. The original military orders were the Knights Templar, the Knights Hospitaller, the Order of Saint James, the Order of Calatrava, and the Teutonic Knights. They arose in the Middle Ages in association with the Crusades, both in the Holy Land, the Baltics, and the Iberian peninsula; their members being dedicated to the protection of pilgrims and Christians, as well as the defence of the Crusader states. They are the predecessors of chivalric orders.

Peter Bartholomew was a French soldier and mystic who was part of the First Crusade as part of the army of Raymond of Saint-Gilles. Peter was initially a servant to William, Lord of Cunhlat.

The crusading movement was a framework of ideologies and institutions that described, regulated, and promoted the Crusades. Members of the Church defined the movement in legal and theological terms based on the concepts of holy war and pilgrimage. Theologically, the movement merged ideas of Old Testament wars that were instigated and assisted by God with New Testament ideas of forming personal relationships with Christ. Crusading was a paradigm that grew from the encouragement of the Gregorian Reform of the 11th century and the movement declined after the Reformation. The ideology continued after the 16th century, but in practical terms dwindled in competition with other forms of religious war and new ideologies.

A man-at-arms was a soldier of the High Medieval to Renaissance periods who was typically well-versed in the use of arms and served as a fully-armoured heavy cavalryman. A man-at-arms could be a knight, or other nobleman, a member of a knight's or nobleman's retinue, or a mercenary in a company serving under a captain. Such men could serve for pay or through a feudal obligation. The terms knight and man-at-arms are often used interchangeably, but while all knights equipped for war were men-at-arms, not all men-at-arms were knights.

During the period of the Crusades, turcopoles were locally recruited mounted archers and light cavalry employed by the Byzantine Empire and the Crusader states. A leader of these auxiliaries was designated as Turcopolier, a title subsequently given to a senior officer in the Knights Templars and the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, in charge of the coastal defences of Rhodes and Malta.

The siege of Jerusalem was waged by European forces of the First Crusade, resulting in the capture of the Holy City of Jerusalem from the Muslim Fatimid Caliphate, and laying the foundation for the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem, which lasted almost two centuries. The capture of Jerusalem was the final major battle of the first of the Crusades to occupy the Holy Land begun in 1095. A number of eyewitness accounts of the siege were recorded, the most quoted being that from the anonymous Gesta Francorum.

The Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, also called Order of the Holy Sepulchre or Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, is a Catholic order of knighthood under the protection of the Holy See. The pope is the sovereign of the order. The order creates canons as well as knights, with the primary mission to "support the Christian presence in the Holy Land". It is an internationally recognized order of chivalry.

Conor Kostick is an Irish historian and writer living in Dublin. He is the author of many works of history and fiction. A former chairperson of the Irish Writers Union and member of the board of the National Library of Ireland, he has won a number of awards.

Gervase of Bazoches, who is also known as Gervaise, was Prince of Galilee from 1105/1106 until his death. He was born into a French noble family but migrated to the Holy Land, where King Baldwin I of Jerusalem made him senechal in the early 1100s and appointed him prince of Galilee in 1105/1106. Gervase was captured during a raid by Toghtekin, atabeg of Damascus, who had Gervase executed after Baldwin I refused to surrender three important towns in exchange for Gervase's release.

The Battle of Civetot was fought between the forces of the People's Crusade and of the Seljuk Turks of Anatolia on 21 October 1096. The battle brought an end to the People's Crusade, before the Princes' Crusade.

The miles Christianus or miles Christi is a Christian allegory based on New Testament military metaphors, especially the Armor of God metaphor of military equipment standing for Christian virtues and on certain passages of the Old Testament from the Latin Vulgate. The plural of Latin miles (soldier) is milites or the collective militia.

Helen J. Nicholson FRHistS FLSW is Emerita Professor of Medieval History and former Head of the History Department at Cardiff University. She is a world-leading expert on the military religious orders and the Crusades, including the history of the Templars.