This article needs additional citations for verification .(February 2013) |

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

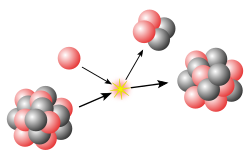

In physics, mirror nuclei are a pair of isobars of two different elements where the number of protons of isobar one (Z1) equals the number of neutrons of isobar two (N2) and the number of protons of isotope two (Z2) equals the number of neutrons in isotope one (N1); in short: Z1 = N2 and Z2 = N1. This implies that the mass numbers of the isotopes are the same: N1 + Z1 = N2 + Z2.

Examples of mirror nuclei include:

| Isobar 1 | Z1 | N1 | Isobar 2 | Z2 | N2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3H | 1 | 2 | 3He | 2 | 1 |

| 14C | 6 | 8 | 14O | 8 | 6 |

| 15N | 7 | 8 | 15O | 8 | 7 |

| 24Na | 11 | 13 | 24Al | 13 | 11 |

Pairs of mirror nuclei have the same spin and parity. If we constrain to odd number of nucleons (A=Z+N) then we find mirror nuclei that differ from one another by exchanging a proton by a neutron. Interesting to observe is their binding energy which is mainly due to the strong interaction and also due to Coulomb interaction. Since the strong interaction is invariant to protons and neutrons one can expect these mirror nuclei to have very similar binding energies. [1] [2]

In 2020 strontium-73 and bromine-73 were found to not behave as expected. [3] The ground state of 73

35Br has spin and parity 1/2−, whereas the ground state of 73

38Sr was inferred to have spin and parity 5/2−, matching a low-lying 27 keV excited state of 73

35Br. [4]