Chinese poetry is poetry written, spoken, or chanted in the Chinese language, and a part of the Chinese literature. While this last term comprises Classical Chinese, Standard Chinese, Mandarin Chinese, Yue Chinese, and other historical and vernacular forms of the language, its poetry generally falls into one of two primary types, Classical Chinese poetry and Modern Chinese poetry.

Classical Chinese poetry is traditional Chinese poetry written in Classical Chinese and typified by certain traditional forms, or modes; traditional genres; and connections with particular historical periods, such as the poetry of the Tang dynasty. The existence of classical Chinese poetry is documented at least as early as the publication of the Classic of Poetry (Shijing). Various combinations of forms and genres have developed over the ages. Many or most of these poetic forms were developed by the end of the Tang dynasty, in 907 CE.

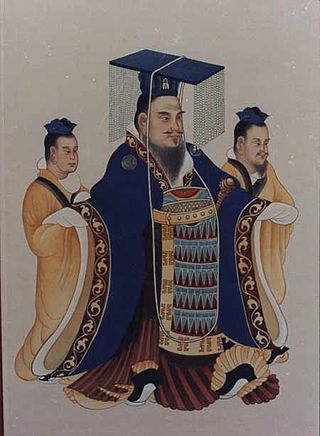

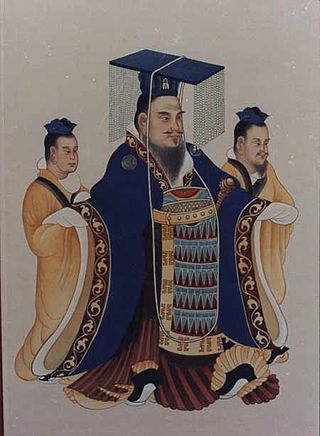

Emperor Wu of Han, born Liu Che and courtesy name Tong, was the seventh emperor of the Han dynasty from 141 to 87 BC. His reign lasted 54 years – a record not broken until the reign of the Kangxi Emperor more than 1,800 years later – and remains the record for ethnic Han emperors. His reign resulted in a vast expansion of geopolitical influence for the Chinese civilization, and the development of a strong centralized state via governmental policies, economical reorganization and promotion of a hybrid Legalist–Confucian doctrine. In the field of historical social and cultural studies, Emperor Wu is known for his religious innovations and patronage of the poetic and musical arts, including development of the Imperial Music Bureau into a prestigious entity. It was also during his reign that cultural contact with western Eurasia was greatly increased, directly and indirectly.

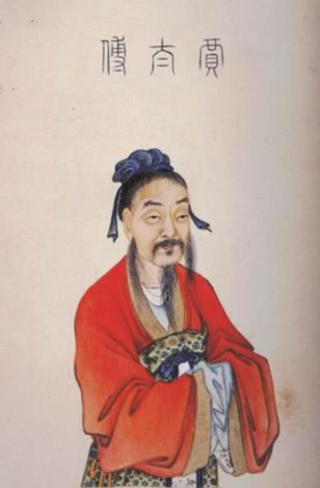

Tao Yuanming, also known as Tao Qian, was a Chinese poet and politician who was one of the best-known poets during the Six Dynasties period. He was born during the Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420) and died during the Liu Song (420–479) dynasty. Tao Yuanming spent much of his life in reclusion, living in the countryside, farming, reading, drinking wine, receiving the occasional guest, and writing poems in which he often reflected on the pleasures and difficulties of life, as well as his decision to withdraw from civil service. Tao's simple and direct style was somewhat at odds with the norms for literary writing in his time. In the Tang dynasty (618–907), he was well known as a recluse. During the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), influential literati figures such as Su Shi (1037–1101) declared him a paragon of authenticity and spontaneity in poetry, predicting that Tao Yuanming would achieve lasting literary fame. However, Tao Yuanming's inclusion in the 6th century literary anthology Wen Xuan argues for at least a beginning of fame in his own era, at least in his own birth area. Tao Yuanming would later be regarded as the foremost representative of what we now know as Fields and Gardens poetry. Tao Yuanming found inspiration in the beauty and serenity of the natural world close at hand. Tao Yuanming is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu by Jin Guliang.

Yuefu are Chinese poems composed in a folk song style. The term originally literally meant "Music Bureau", a reference to the imperial Chinese governmental organization(s) originally charged with collecting or writing the lyrics, later the term yuefu was applied to later literary imitations or adaptations of the Music Bureau's poems. The use of fu in yuefu is different from the other Chinese term fu that refers to a type of poetry or literature: although homonyms in English, the other fu is a rhapsodic poetry/prose form of literature.

The grand chancellor, also translated as counselor-in-chief, chancellor, chief councillor, chief minister, imperial chancellor, lieutenant chancellor and prime minister, was the highest-ranking executive official in the imperial Chinese government. The term was known by many different names throughout Chinese history, and the exact extent of the powers associated with the position fluctuated greatly, even during a particular dynasty.

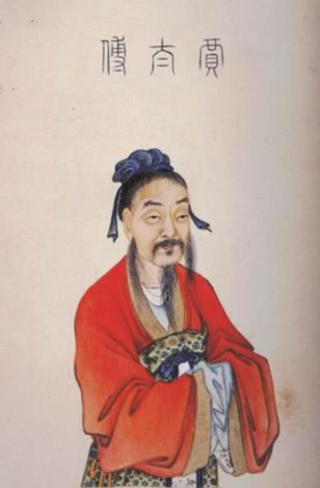

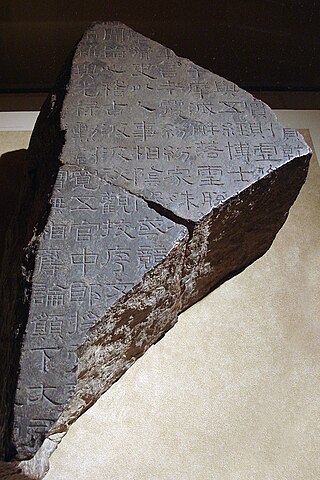

Jia Yi was a Chinese essayist, poet and politician of the Western Han dynasty, best known as one of the earliest known writers of fu rhapsody and for his essay "Disquisition Finding Fault with Qin", which criticises the Qin dynasty and describes Jia's opinions on the reasons for its collapse. In particular, he is famous for his two fu, On the Owl (鵩鳥賦) and his Lament for Qu Yuan (吊屈原賦). He is also the author of the treatise Xinshu (新書), containing political and educational insights.

Fu Xuan (217–278), courtesy name Xiuyi, was a Chinese historian, poet, and politician who lived in the state of Cao Wei during the Three Kingdoms period and later under the Jin dynasty. He was one of the most prolific authors of fu poetry of his time. He was a grandson of Fu Xie (傅燮), a son of Fu Gan (傅幹), and the father of Fu Xian (傅咸).

Shen Yue, courtesy name Xiuwen (休文), was a Chinese historian, music theorist, poet, and politician born in Huzhou, Zhejiang. He served emperors under the Liu Song dynasty, the Southern Qi dynasty, and the Liang dynasty of Southern Dynasties era.

The arts of China have varied throughout its ancient history, divided into periods by the ruling dynasties of China and changing technology, but still containing a high degree of continuity. Different forms of art have been influenced by great philosophers, teachers, religious figures and even political leaders. The arrival of Buddhism and modern Western influence produced especially large changes. Chinese art encompasses fine arts, folk arts and performance arts.

Classical Chinese poetry forms are poetry forms or modes which typify the traditional Chinese poems written in Literary Chinese or Classical Chinese. Classical Chinese poetry has various characteristic forms, some attested to as early as the publication of the Classic of Poetry, dating from a traditionally, and roughly, estimated time of around 10th–7th century BCE. The term "forms" refers to various formal and technical aspects applied to poems: this includes such poetic characteristics as meter, rhythm, and other considerations such as vocabulary and style. These forms and modes are generally, but not invariably, independent of the Classical Chinese poetry genres. Many or most of these were developed by the time of the Tang Dynasty, and the use and development of Classical Chinese poetry and genres actively continued up until the May Fourth Movement, and still continues even today in the 21st century.

Guo Maoqian was a Song dynasty poetry anthologist. He compiled an important collection of lyrical pieces in his work Anthology of Yuefu Poetry (樂府詩集), which contains almost all of the surviving Music Bureau style, or Yuefu from the Han dynasty through the Tang dynasty and to the Five Dynasties, and which includes such famous poems as "Hua Mulan".

Han poetry as a style of poetry resulted in significant poems which are still preserved today, and whose origins are associated with the Han dynasty era of China, 206 BC – 220 AD, including the Wang Mang interregnum. The final years at the end of the Han era often receive special handling for purposes of literary analysis because, among other things, the poetry and culture of this period is less than typical of the Han period, and has important characteristics of its own, or it shares literary aspects with the subsequent Three Kingdoms period. This poetry reflects one of the poetry world's more important flowerings, as well as being a special period in Classical Chinese poetry, particularly in regard to the development of the quasipoetic fu; the activities of the Music Bureau in connection with the collection of popular ballads and the resultant development of what would eventually become known as the yuefu, or as the rhapsodic formal style; and, finally, towards the end of the Han dynasty, the development of a new style of shi poetry, as the later development of the yuehfu into regular, fixed-line length forms makes it difficult to distinguish in form from the shi form of poetic verse, and at what point specific poems are classified as one or the other is somewhat arbitrary. Another important poetic contribution from the Han era is the compilation of the Chuci anthology, which contains some of the oldest and most important poetic verses to be preserved from ancient China, as well as the transmission of the Shijing anthology.

Jian'an poetry or Chien-an poetry, refers to the styles of Chinese poetry particularly associated with the end of the Han dynasty and the beginning of the Six Dynasties era of China. This poetry category is particularly important because, in the case of the Jian'an poetic developments, there is a special difficulty in matching the chronology of changes in poetry with the usual Chinese dynastic chronology based on the political leadership of the times. For example, according to Burton Watson, the first major poet of the new shi style that emerged at this time was Cao Zhi, one of the sons of Cao Cao, a family which came into power at the end of Han and developed further during the Three Kingdoms era of the Six Dynasties period.

Six Dynasties poetry refers to those types or styles of poetry particularly associated with the Six Dynasties era of China. This poetry reflects one of the poetry world's more important flowerings, as well as being a unique period in Classical Chinese poetry, which, over this time period, developed a poetry with special emphasis on romantic love, gender roles, and human relationships. The Six Dynasties era is sometimes known as the "Age of Fragmentation", because China as a whole through this period lacked unification as a state, at least for any extended period of time; and, instead, many states rose and fell, often overlapping in existence with other states. Which of the various states and dynasties constituted the "6" dynasties of the Six Dynasties period varies somewhat according to which of the traditional selection criteria are chosen. The Six Dynasties era covers several somewhat overlapping main periods including all of the following: the Three Kingdoms (220–280), Jin dynasty, the Sixteen Kingdoms, and the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589). Sometimes, chronological discrepancies occur in regard to the turbulent political events of the time, from which these traditional historical-era designations derive, together with the somewhat different chronology of poetic developments. Thus, neither the lives of the poets nor the trends in their poetry fit gently and neatly together with these period dates. Furthermore, conversions to the Common Era dating system can create further complications. However, regardless of the chronological difficulties, major developments of poetry during the Six Dynasties include formalizing the distinction between the Jian'an era regular yuefu and the shi style poetry, further development of the fu, theoretical work on technique, and the preservation of both Six Dynasties and earlier poetry by collecting and publishing many of the pieces which survive today into various anthologies consisting all or in part of poetry.

The History of fu poetry covers the beginnings of the Chinese literary genre of fu. The term fu describes literary works which have certain characteristics of their own. English lacks an equivalent native term. Sometimes called "rhapsodies", sometimes called "rhyme-prose", fu are characterized by qualities of both poetry and prose: both are obligatory. The fu form of literary work is a treatment in a poetic manner, wherein some topic of interest, such as an exotic object, a profound feeling, or an encyclopedic subject is described and rhapsodized upon, in exhaustive detail and various angles of view. And, for a piece to be truly considered to be within the fu genre, it must follow the rules of this form, in terms of structure, meter, and so on.

Geese are an important motif in Chinese poetry. Examples of goose imagery have an important place in Chinese poetry ranging from the Shijing and the Chu Ci poets through the poets of Han poetry and later poets of Tang poetry such as Li Bai, Wang Wei, Du Fu, and the Xiaoxiang poetry, especially in the poetry of the Song dynastic era. Various poetic concepts could be communicated by the inclusion of the imagery of geese in a poem, and the understanding of allusions to a goose or geese can help provide key insights into the poems of Classical Chinese poetry. Chinese sources typically distinguish between two types of geese, the domestic goose, and the wild goose: of the two, the wild goose is the more important for poetry, whether as significant of migratory seasonal change, or as "bearing a message of love from afar", by persons separated by a great distance, or as the "lone goose", bereft of both mate and flock.

The Advisors Alliance is a 2017 Chinese two-part television series based on the life of Sima Yi, a government official and military general who lived in the late Eastern Han dynasty and Three Kingdoms period of China. The series starred Wu Xiubo as the main character, with Liu Tao, Li Chen, Janine Chang, Tang Yixin, Yu Hewei and Wang Luoyong playing supporting roles. The first part of the series started airing on Jiangsu TV and Anhui TV on 22 June 2017. The second part started airing on Youku on 8 December 2017.

The military history of the Jin dynasty and the Sixteen Kingdoms encompasses the period of Chinese military activities from 266 AD to 420 AD. The Jin dynasty is usually divided into the Western Jin and Eastern Jin in Chinese historiography. Western Jin lasted from its usurpation of Cao Wei in 266 to 316 when the Uprising of the Five Barbarians split the empire and created a number of barbarian states in the north. The Jin court relocated to Jiankang, starting the era of Eastern Jin, which ended in 420 when it was usurped by Liu Yu, who founded the Liu Song dynasty.

Zhuang Ji had the courtesy name (zi) of Fuzi (夫子), literally, "the Master"; and, he was later sometimes referred to as Yan Ji (嚴忌) due to a naming taboo based on the personal name of an emperor titled. Zhuang Ji flourished in the second century BCE as an early Han dynasty writer of literature and court attendant. He is notable for being one of the most published poets ever, due to having authored the piece "Ai shi ming", or "Alas That My Lot Was Not Cast", collected in the repeatedly re-published Chuci collection of verse: although just because Zhuang Ji's work was prolifically published as being included in a popular and early anthology does not necessarily mean that he has been notable for his poetic excellence. None of his other works are known to have survived. Zhuang Ji's biography is also sparse, although he is known to have been born in Wu state and later found refuge in Liang state. Both Wu and Liang were then semi-independent states, regions of the Han dynasty, directly controlled by their local ruler, in these two cases members of the royal house of Han. Zhuang Ji pursued a literary career, from which he attained his fame, though he seems to have at least initially made a living attending his local ruler's court, though in what function is unknown. During Zhuang Ji's life, political turmoil and social upheaval greatly informed his contributions to literature, indeed this kind of state of affairs is very evident in "Ai shi ming". THEREFORE Zhuang Ji aspired to eventually join the central imperial court of Han to further his career or literary pursuits is unknown; however, it is known that he found patronage in two different regional state courts, in his native Wu, and later in Liang, then a center of literary activity. Zhuang Ji experienced turbulent and dangerous events which happened to occur in the places in which he dwelt, yet still found time and energy for a literary calling.