In poetry, metre or meter is the basic rhythmic structure of a verse or lines in verse. Many traditional verse forms prescribe a specific verse metre, or a certain set of metres alternating in a particular order. The study and the actual use of metres and forms of versification are both known as prosody.

Poetry is a form of literary art that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, literal or surface-level meanings. Any particular instance of poetry is called a poem and is written by a poet.

Chinese poetry is poetry written, spoken, or chanted in the Chinese language, and a part of the Chinese literature. While this last term comprises Classical Chinese, Standard Chinese, Mandarin Chinese, Yue Chinese, and other historical and vernacular forms of the language, its poetry generally falls into one of two primary types, Classical Chinese poetry and Modern Chinese poetry.

Classical Chinese poetry is traditional Chinese poetry written in Classical Chinese and typified by certain traditional forms, or modes; traditional genres; and connections with particular historical periods, such as the poetry of the Tang dynasty. The existence of classical Chinese poetry is documented at least as early as the publication of the Classic of Poetry (Shijing). Various combinations of forms and genres have developed over the ages. Many or most of these poetic forms were developed by the end of the Tang dynasty, in 907 CE.

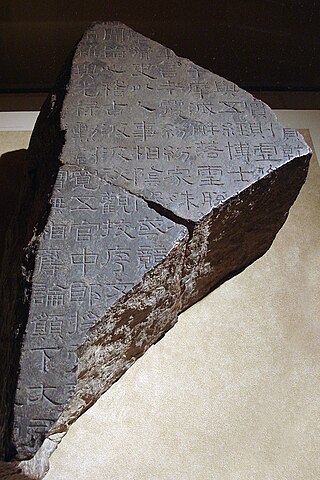

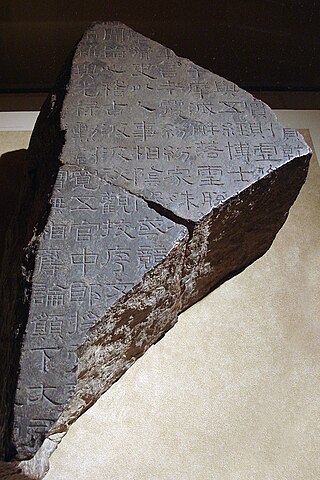

The Classic of Poetry, also Shijing or Shih-ching, translated variously as the Book of Songs, Book of Odes, or simply known as the Odes or Poetry, is the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, comprising 305 works dating from the 11th to 7th centuries BC. It is one of the "Five Classics" traditionally said to have been compiled by Confucius, and has been studied and memorized by scholars in China and neighboring countries over two millennia. It is also a rich source of chengyu that are still a part of learned discourse and even everyday language in modern Chinese. Since the Qing dynasty, its rhyme patterns have also been analysed in the study of Old Chinese phonology.

Cí, also known as chángduǎnjù and shīyú, is a type of lyric poetry in the tradition of Classical Chinese poetry that also draws upon folk traditions. Cí, also known as "song lyrics," use various poetic meters derived from a base set of fixed pattern forms, using fixed-rhythm, fixed-tone, and line-lengths varying according that of the model examples. The rhythmic and tonal pattern of the cí are based upon certain, definitive musical song tunes (cípái), and in many cases the name of the musical tune is given in the title of a cí piece, in a form such as "after ...."

Shi and shih are romanizations of the character 詩/诗, the Chinese word for all poetry generally and across all languages.

Yuefu are Chinese poems composed in a folk song style. The term originally literally meant "Music Bureau", a reference to the imperial Chinese governmental organization(s) originally charged with collecting or writing the lyrics, later the term yuefu was applied to later literary imitations or adaptations of the Music Bureau's poems. The use of fu in yuefu is different from the other Chinese term fu that refers to a type of poetry or literature: although homonyms in English, the other fu is a rhapsodic poetry/prose form of literature.

The Three Hundred Tang Poems is an anthology of poems from the Chinese Tang dynasty (618–907). It was first compiled around 1763 by Sun Zhu (1722–1778), who was a Qing Dynasty scholar and was also known as Hengtang Tuishi. Various later editions also exist. All editions contain slightly more than 300 total poems. The number 300 was a classic number for a poetry collection due to the influence of the Classic of Poetry, which was generally known as The Three Hundred Poems.

The arts of China have varied throughout its ancient history, divided into periods by the ruling dynasties of China and changing technology, but still containing a high degree of continuity. Different forms of art have been influenced by great philosophers, teachers, religious figures and even political leaders. The arrival of Buddhism and modern Western influence produced especially large changes. Chinese art encompasses fine arts, folk arts and performance arts.

Jueju, or Chinese quatrain, is a type of jintishi that grew popular among Chinese poets in the Tang dynasty (618–907), although traceable to earlier origins. Jueju poems are always quatrains; or, more specifically, a matched pair of couplets, with each line consisting of five or seven syllables.

Vietnamese poetry originated in the form of folk poetry and proverbs. Vietnamese poetic structures include Lục bát, Song thất lục bát, and various styles shared with Classical Chinese poetry forms, such as are found in Tang poetry; examples include verse forms with "seven syllables each line for eight lines," "seven syllables each line for four lines", and "five syllables each line for eight lines." More recently there have been new poetry and free poetry.

The Music Bureau served in the capacity of an organ of various imperial government bureaucracies of China: discontinuously and in various incarnations, the Music Bureau was charged directly, by the emperor, or indirectly, through the royal government to perform various tasks related to music, poetry, entertainment, or religious worship. These tasks included both musical and lyrical research and development, and also directing performances.

Han poetry as a style of poetry resulted in significant poems which are still preserved today, and whose origins are associated with the Han dynasty era of China, 206 BC – 220 AD, including the Wang Mang interregnum. The final years at the end of the Han era often receive special handling for purposes of literary analysis because, among other things, the poetry and culture of this period is less than typical of the Han period, and has important characteristics of its own, or it shares literary aspects with the subsequent Three Kingdoms period. This poetry reflects one of the poetry world's more important flowerings, as well as being a special period in Classical Chinese poetry, particularly in regard to the development of the quasipoetic fu; the activities of the Music Bureau in connection with the collection of popular ballads and the resultant development of what would eventually become known as the yuefu, or as the rhapsodic formal style; and, finally, towards the end of the Han dynasty, the development of a new style of shi poetry, as the later development of the yuehfu into regular, fixed-line length forms makes it difficult to distinguish in form from the shi form of poetic verse, and at what point specific poems are classified as one or the other is somewhat arbitrary. Another important poetic contribution from the Han era is the compilation of the Chuci anthology, which contains some of the oldest and most important poetic verses to be preserved from ancient China, as well as the transmission of the Shijing anthology.

Jian'an poetry or Chien-an poetry, refers to the styles of Chinese poetry particularly associated with the end of the Han dynasty and the beginning of the Six Dynasties era of China. This poetry category is particularly important because, in the case of the Jian'an poetic developments, there is a special difficulty in matching the chronology of changes in poetry with the usual Chinese dynastic chronology based on the political leadership of the times. For example, according to Burton Watson, the first major poet of the new shi style that emerged at this time was Cao Zhi, one of the sons of Cao Cao, a family which came into power at the end of Han and developed further during the Three Kingdoms era of the Six Dynasties period.

Gushi, is one of the main poetry forms defined in Classical Chinese poetry, literally meaning "old poetry" or "old style poetry": gushi is a technical term for certain historically exemplary poems, together with later poetry composed in this formal style.

Regulated verse – also known as Jintishi – is a development within Classical Chinese poetry of the shi main formal type. Regulated verse is one of the most important of all Classical Chinese poetry types. Although often regarded as a Tang dynasty innovation, the origin of regulated verse within the Classical Chinese poetic tradition is associated with Shen Yue (441–513), based on his "four tones and eight defects" (四聲八病) theory regarding tonality. There are three types of regulated verse: the eight-lined lüshi, the four-lined jueju, and the linked couplets of indeterminate length pailu. All regulated verse forms are rhymed on the even lines, with one rhyme being used throughout the poem. Also, and definitionally, the tonal profile of the poem is controlled. Furthermore, semantic and tonal parallelism is generally required of certain interior couplets. During the Tang dynasty, the "Shen-Song" team of Shen Quanqi and Song Zhiwen greatly contributed to the development of this Classical Chinese verse form.

Yuan poetry refers to those types or styles of poetry particularly associated with the era of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), in China. Although the poetic forms of past literature were continued, the Yuan period is particularly known for the development of the poetic aspects included in the complex mix of different art forms which characterize Chinese opera, namely the qu or fixed-tone pattern type of verses that were delivered by the actors of these shows. Although the language of Yuan poetry is still generally considered to be Classical Chinese, a certain vernacular aspect reflecting linguistic changes can be seen in some of the fixed-rhythm verse forms, such as Yuan ci and qu. Certain aspects of Yuan poetry can be understood in the context of the social and political changes which took place as part of the process of the Mongol conquest of the Jin and Song Dynasties and their subsequent establishment of the Yuan dynasty.

Cao Cao (155–220) was a warlord who rose to power towards the final years of the Eastern Han dynasty and became the de facto head of government in China. He laid the foundation for what was to become the state of Cao Wei (220–265), founded by his son and successor Cao Pi, in the Three Kingdoms period (220–280). Poetry, among other things, was one of his cultural legacies.