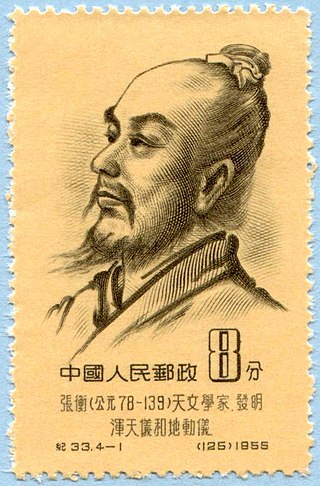

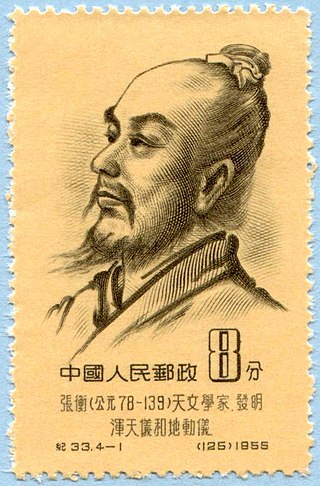

Zhang Heng, formerly romanized as Chang Heng, was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman who lived during the Han dynasty. Educated in the capital cities of Luoyang and Chang'an, he achieved success as an astronomer, mathematician, seismologist, hydraulic engineer, inventor, geographer, cartographer, ethnographer, artist, poet, philosopher, politician, and literary scholar.

Chinese poetry is poetry written, spoken, or chanted in the Chinese language, and a part of the Chinese literature. While this last term comprises Classical Chinese, Standard Chinese, Mandarin Chinese, Yue Chinese, and other historical and vernacular forms of the language, its poetry generally falls into one of two primary types, Classical Chinese poetry and Modern Chinese poetry.

Classical Chinese poetry is traditional Chinese poetry written in Classical Chinese and typified by certain traditional forms, or modes; traditional genres; and connections with particular historical periods, such as the poetry of the Tang dynasty. The existence of classical Chinese poetry is documented at least as early as the publication of the Classic of Poetry (Shijing). Various combinations of forms and genres have developed over the ages. Many or most of these poetic forms were developed by the end of the Tang dynasty, in 907 CE.

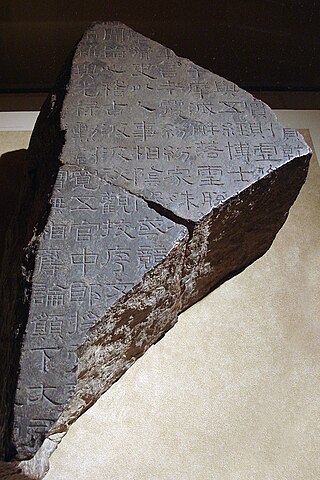

The Classic of Poetry, also Shijing or Shih-ching, translated variously as the Book of Songs, Book of Odes, or simply known as the Odes or Poetry, is the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, comprising 305 works dating from the 11th to 7th centuries BCE. It is one of the "Five Classics" traditionally said to have been compiled by Confucius, and has been studied and memorized by scholars in China and neighboring countries over two millennia. It is also a rich source of chengyu that are still a part of learned discourse and even everyday language in modern Chinese. Since the Qing dynasty, its rhyme patterns have also been analysed in the study of Old Chinese phonology.

Ban Gu was a Chinese historian, politician, and poet best known for his part in compiling the Book of Han, the second of China's 24 dynastic histories. He also wrote a number of fu, a major literary form, part prose and part poetry, which is particularly associated with the Han era. A number of Ban's fu were collected by Xiao Tong in the Wen Xuan.

Yuefu are Chinese poems composed in a folk song style. The term originally literally meant "Music Bureau", a reference to the imperial Chinese governmental organization(s) originally charged with collecting or writing the lyrics, later the term yuefu was applied to later literary imitations or adaptations of the Music Bureau's poems. The use of fu in yuefu is different from the other Chinese term fu that refers to a type of poetry or literature: although homonyms in English, the other fu is a rhapsodic poetry/prose form of literature.

The Chu ci, variously translated as Verses of Chu, Songs of Chu, or Elegies of Chu, is an ancient anthology of Chinese poetry including works traditionally attributed mainly to Qu Yuan and Song Yu from the Warring States period, and also a large number of works composed several centuries later, during the Han dynasty. The traditional version of the Chu ci contains 17 major sections, anthologized with its current contents by Wang Yi, a 2nd-century AD librarian who served under Emperor Shun of Han. The early Classical Chinese poetry is mainly known through the two anthologies the Chu ci and the Shi jing.

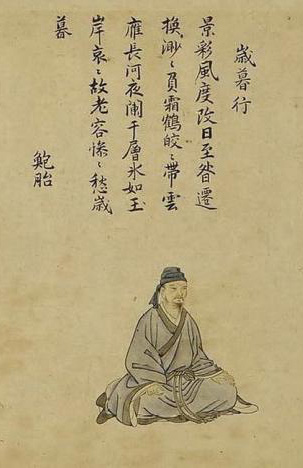

Sima Xiangru was a Chinese musician, poet, and politician who lived during the Western Han dynasty. Sima is a significant figure in the history of Classical Chinese poetry, and is generally regarded as the greatest of all composers of Chinese fu rhapsodies. His poetry includes his invention or at least development of the fu form, applying new metrical rhythms to the lines of poetry, which he mixed with lines of prose, and provided with several of what would in ensuing centuries become among a group of common set topics for this genre. Sima Xiangru was also versatile enough to write in the Chu ci style, while it was enjoying a renaissance, and he also wrote lyrics in what would become known as the yuefu formal style.

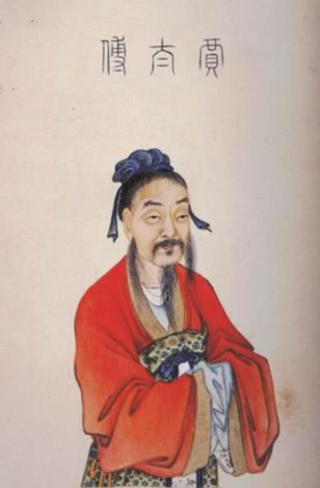

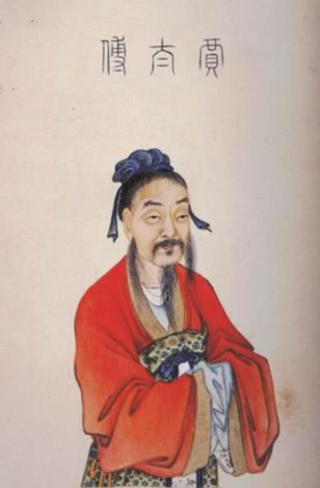

Jia Yi was a Chinese essayist, poet and politician of the Western Han dynasty, best known as one of the earliest known writers of fu rhapsody and for his essay "Disquisition Finding Fault with Qin", which criticises the Qin dynasty and describes Jia's opinions on the reasons for its collapse. In particular, he is famous for his two fu, On the Owl (鵩鳥賦) and his Lament for Qu Yuan (吊屈原賦). He is also the author of the treatise Xinshu (新書), containing political and educational insights.

Guo Pu, courtesy name Jingchun, was a Chinese historian, poet, and writer during the Eastern Jin period, and is best known as one of China's foremost commentators on ancient texts. Guo was a Taoist mystic, geomancer, collector of strange tales, editor of old texts, and erudite commentator. He was the first commentator of the Shan Hai Jing and so probably, with the noted Han bibliographer Liu Xin, was instrumental in preserving this valuable mythological and religious text. Guo Pu was the well educated son of a governor. He was a natural historian and a prolific writer of the Jin dynasty. He is the author of The Book of Burial, the first-ever and the most authoritative source of feng shui doctrine and the first book to address the concept of feng shui in the history of China, making Guo Pu the first person historically to define feng shui, and therefore, Guo Pu is usually called the father of feng shui in China.

Yang Xiong was a Chinese philosopher, poet, and politician of the Western Han dynasty known for his philosophical writings and fu poetry compositions.

Fu, often translated "rhapsody" or "poetic exposition", is a form of Chinese rhymed prose that was the dominant literary form in China during the Han dynasty. Fu are intermediary pieces between poetry and prose in which a place, object, feeling, or other subject is described and rhapsodized in exhaustive detail and from as many angles as possible. Fu's distinguishing characteristics include alternating rhyme and prose, varying line length, close alliteration, onomatopoeia, loose parallelism, and extensive cataloging of their topics. Classical fu composers often tried to use as wide a vocabulary as possible, and their compositions are usually replete with rare and archaic Chinese words. They were not sung like songs, but were recited or chanted.

The Wen Xuan, usually translated Selections of Refined Literature, is one of the earliest and most important anthologies of Chinese poetry and literature, and is one of the world's oldest literary anthologies to be arranged by topic. It is a selection of what were judged to be the best poetic and prose pieces from the late Warring States period to the early Liang dynasty, excluding the Chinese Classics and philosophical texts. The Wen Xuan preserves most of the greatest fu rhapsody and shi poetry pieces from the Qin and Han dynasties, and for much of pre-modern history was one of the primary sources of literary knowledge for educated Chinese.

New Songs from the Jade Terrace is an anthology of early medieval Chinese poetry in the romantic or semi-erotic "palace style" that dates to the late Southern dynasties period (420–589). Most editions of New Songs contain 670 poems by many different authors, mainly comprising pentasyllabic poetry but also some yuefu lyrical verse and other types of poems. New Songs was probably compiled around the early to mid-530s by Xu Ling, an official and scholar who served at the court of Xiao Gang, a crown prince of the Liang dynasty (502–587) who later ascended the throne as Emperor Jianwen of Liang.

The Music Bureau served in the capacity of an organ of various imperial government bureaucracies of China: discontinuously and in various incarnations, the Music Bureau was charged directly, by the emperor, or indirectly, through the royal government to perform various tasks related to music, poetry, entertainment, or religious worship. These tasks included both musical and lyrical research and development, and also directing performances.

Han poetry as a style of poetry resulted in significant poems which are still preserved today, and whose origins are associated with the Han dynasty era of China, 206 BC – 220 AD, including the Wang Mang interregnum. The final years at the end of the Han era often receive special handling for purposes of literary analysis because, among other things, the poetry and culture of this period is less than typical of the Han period, and has important characteristics of its own, or it shares literary aspects with the subsequent Three Kingdoms period. This poetry reflects one of the poetry world's more important flowerings, as well as being a special period in Classical Chinese poetry, particularly in regard to the development of the quasipoetic fu; the activities of the Music Bureau in connection with the collection of popular ballads and the resultant development of what would eventually become known as the yuefu, or as the rhapsodic formal style; and, finally, towards the end of the Han dynasty, the development of a new style of shi poetry, as the later development of the yuehfu into regular, fixed-line length forms makes it difficult to distinguish in form from the shi form of poetic verse, and at what point specific poems are classified as one or the other is somewhat arbitrary. Another important poetic contribution from the Han era is the compilation of the Chuci anthology, which contains some of the oldest and most important poetic verses to be preserved from ancient China, as well as the transmission of the Shijing anthology.

Six Dynasties poetry refers to those types or styles of poetry particularly associated with the Six Dynasties era of China. This poetry reflects one of the poetry world's more important flowerings, as well as being a unique period in Classical Chinese poetry, which, over this time period, developed a poetry with special emphasis on romantic love, gender roles, and human relationships. The Six Dynasties era is sometimes known as the "Age of Fragmentation", because China as a whole through this period lacked unification as a state, at least for any extended period of time; and, instead, many states rose and fell, often overlapping in existence with other states. Which of the various states and dynasties constituted the "6" dynasties of the Six Dynasties period varies somewhat according to which of the traditional selection criteria are chosen. The Six Dynasties era covers several somewhat overlapping main periods including all of the following: the Three Kingdoms (220–280), Jin dynasty, the Sixteen Kingdoms, and the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589). Sometimes, chronological discrepancies occur in regard to the turbulent political events of the time, from which these traditional historical-era designations derive, together with the somewhat different chronology of poetic developments. Thus, neither the lives of the poets nor the trends in their poetry fit gently and neatly together with these period dates. Furthermore, conversions to the Common Era dating system can create further complications. However, regardless of the chronological difficulties, major developments of poetry during the Six Dynasties include formalizing the distinction between the Jian'an era regular yuefu and the shi style poetry, further development of the fu, theoretical work on technique, and the preservation of both Six Dynasties and earlier poetry by collecting and publishing many of the pieces which survive today into various anthologies consisting all or in part of poetry.

Wang Bao, courtesy name Ziyuan (子淵), was a Chinese poet during the Western Han Dynasty. He was well versed in the Classical Chinese poetry tradition. He was involved in the Chu Ci poetry revival which took place in the second part of Emperor Xuan's reign, and which led to the creation of poetry that would eventually form part of the early poetry anthology by the same name, compiled by Wang Yi. Chu Ci means "literature of Chu", Chu being the area of a former independent kingdom, located in what was from the viewpoint of the Han Dynasty the south of China. Wang Bao is particularly known today as the author of the Chu Ci section "Nine Regrets". His poetry was not as famous as "Li Sao" or "Heavenly Questions". Indeed sometimes Qu Yuan has been credited as the author of his poetry. Wang Bao's works were included in one of the two major early anthologies of Chinese poetry which has helped to secure Wang Bao's legacy as a poet and author. Wang Bao became famous during the reign of Han Dynasty emperor Emperor Xuan, and he attended the courts of the emperor and the prince, his presumptive heir.

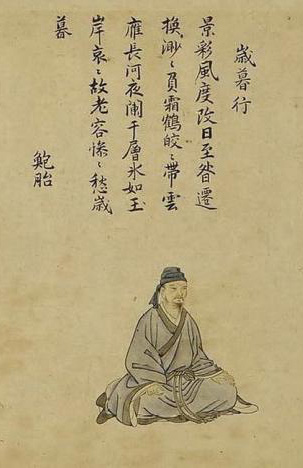

Bao Zhao was a Chinese poet, writer, and official known for his shi poetry, fu rhapsodies, and parallel prose who lived during the Liu Song dynasty (420–479). Bao's best known surviving work is his "Fu on the Ruined City", a long fu rhapsody on the ruined city of Guangling.

Liu Xijun, also known as Princess Xijun (細君公主), Princess of Jiangdu or the Princess of Wusun, was a princess of the Han dynasty sent to marry the King of Wusun as marriage alliance. A poem said to be by her is one of the earliest known Chinese poems attributable to a named woman.