Catalysis is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst. Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quickly, very small amounts of catalyst often suffice; mixing, surface area, and temperature are important factors in reaction rate. Catalysts generally react with one or more reactants to form intermediates that subsequently give the final reaction product, in the process of regenerating the catalyst.

Chymotrypsin (EC 3.4.21.1, chymotrypsins A and B, alpha-chymar ophth, avazyme, chymar, chymotest, enzeon, quimar, quimotrase, alpha-chymar, alpha-chymotrypsin A, alpha-chymotrypsin) is a digestive enzyme component of pancreatic juice acting in the duodenum, where it performs proteolysis, the breakdown of proteins and polypeptides. Chymotrypsin preferentially cleaves peptide amide bonds where the side chain of the amino acid N-terminal to the scissile amide bond (the P1 position) is a large hydrophobic amino acid (tyrosine, tryptophan, and phenylalanine). These amino acids contain an aromatic ring in their side chain that fits into a hydrophobic pocket (the S1 position) of the enzyme. It is activated in the presence of trypsin. The hydrophobic and shape complementarity between the peptide substrate P1 side chain and the enzyme S1 binding cavity accounts for the substrate specificity of this enzyme. Chymotrypsin also hydrolyzes other amide bonds in peptides at slower rates, particularly those containing leucine at the P1 position.

Enzymes are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. Almost all metabolic processes in the cell need enzyme catalysis in order to occur at rates fast enough to sustain life. Metabolic pathways depend upon enzymes to catalyze individual steps. The study of enzymes is called enzymology and the field of pseudoenzyme analysis recognizes that during evolution, some enzymes have lost the ability to carry out biological catalysis, which is often reflected in their amino acid sequences and unusual 'pseudocatalytic' properties.

In chemistry, homogeneous catalysis is catalysis where the catalyst is in same phase as reactants, principally by a soluble catalyst a in solution. In contrast, heterogeneous catalysis describes processes where the catalysts and substrate are in distinct phases, typically solid-gas, respectively. The term is used almost exclusively to describe solutions and implies catalysis by organometallic compounds. Homogeneous catalysis is an established technology that continues to evolve. An illustrative major application is the production of acetic acid. Enzymes are examples of homogeneous catalysts.

In acid catalysis and base catalysis, a chemical reaction is catalyzed by an acid or a base. By Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, the acid is the proton (hydrogen ion, H+) donor and the base is the proton acceptor. Typical reactions catalyzed by proton transfer are esterifications and aldol reactions. In these reactions, the conjugate acid of the carbonyl group is a better electrophile than the neutral carbonyl group itself. Depending on the chemical species that act as the acid or base, catalytic mechanisms can be classified as either specific catalysis and general catalysis. Many enzymes operate by general catalysis.

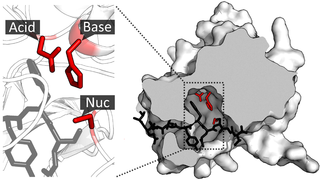

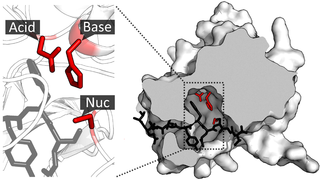

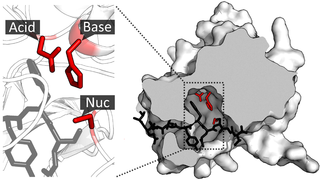

A catalytic triad is a set of three coordinated amino acids that can be found in the active site of some enzymes. Catalytic triads are most commonly found in hydrolase and transferase enzymes. An acid-base-nucleophile triad is a common motif for generating a nucleophilic residue for covalent catalysis. The residues form a charge-relay network to polarise and activate the nucleophile, which attacks the substrate, forming a covalent intermediate which is then hydrolysed to release the product and regenerate free enzyme. The nucleophile is most commonly a serine or cysteine amino acid, but occasionally threonine or even selenocysteine. The 3D structure of the enzyme brings together the triad residues in a precise orientation, even though they may be far apart in the sequence.

Enzyme kinetics is the study of the rates of enzyme-catalysed chemical reactions. In enzyme kinetics, the reaction rate is measured and the effects of varying the conditions of the reaction are investigated. Studying an enzyme's kinetics in this way can reveal the catalytic mechanism of this enzyme, its role in metabolism, how its activity is controlled, and how a drug or a modifier might affect the rate.

Frank Henry Westheimer NAS ForMemRS APS was an American chemist. He taught at the University of Chicago from 1936 to 1954, and at Harvard University from 1953 to 1983, becoming the Morris Loeb Professor of Chemistry in 1960, and Professor Emeritus in 1983. The Westheimer medal was established in his honor in 2002.

The alpha effect refers to the increased nucleophilicity of an atom due to the presence of an adjacent (alpha) atom with lone pair electrons. This first atom does not necessarily exhibit increased basicity compared with a similar atom without an adjacent electron-donating atom, resulting in a deviation from the classical Brønsted-type reactivity-basicity relationship. In other words, the alpha effect refers to nucleophiles presenting higher nucleophilicity than the predicted value obtained from the Brønsted basicity. The representative examples would be high nucleophilicities of hydroperoxide (HO2−) and hydrazine (N2H4). The effect is now well established with numerous examples and became an important concept in mechanistic chemistry and biochemistry. However, the origin of the effect is still controversial without a clear winner.

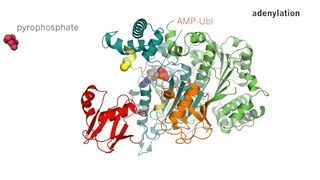

Enzyme catalysis is the increase in the rate of a process by a biological molecule, an "enzyme". Most enzymes are proteins, and most such processes are chemical reactions. Within the enzyme, generally catalysis occurs at a localized site, called the active site.

William Wallace Cleland (January 6, 1930 – March 6, 2013, often cited as W. W. Cleland, and known almost universally as "Mo Cleland", was a University of Wisconsin-Madison biochemistry professor. His research was concerned with enzyme reaction mechanism and enzyme kinetics, especially multiple-substrate enzymes. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1985.

The Hajos–Parrish–Eder–Sauer–Wiechert reaction in organic chemistry is a proline catalysed asymmetric aldol reaction. The reaction is named after the principal investigators of the two groups who reported it simultaneously: Zoltan Hajos and David Parrish from Hoffmann-La Roche and Rudolf Wiechert and co-workers from Schering AG. Discovered in the 1970s the original Hajos-Parrish catalytic procedure – shown in the reaction equation, leading to the optically active bicyclic ketol – paved the way of asymmetric organocatalysis. The Eder-Sauer-Wiechert modification lead directly to the optically active enedione, through the loss of water from the bicyclic ketol shown in figure.

Larry E. Overman is Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at the University of California, Irvine. He was born in Chicago in 1943. Overman obtained a B.A. degree from Earlham College in 1965, and he completed his Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1969, under Howard Whitlock Jr. Professor Overman is a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was the recipient of the Arthur C. Cope Award in 2003, and he was awarded the Tetrahedron Prize for Creativity in Organic Chemistry for 2008.

Asymmetric hydrogenation is a chemical reaction that adds two atoms of hydrogen to a target (substrate) molecule with three-dimensional spatial selectivity. Critically, this selectivity does not come from the target molecule itself, but from other reagents or catalysts present in the reaction. This allows spatial information to transfer from one molecule to the target, forming the product as a single enantiomer. The chiral information is most commonly contained in a catalyst and, in this case, the information in a single molecule of catalyst may be transferred to many substrate molecules, amplifying the amount of chiral information present. Similar processes occur in nature, where a chiral molecule like an enzyme can catalyse the introduction of a chiral centre to give a product as a single enantiomer, such as amino acids, that a cell needs to function. By imitating this process, chemists can generate many novel synthetic molecules that interact with biological systems in specific ways, leading to new pharmaceutical agents and agrochemicals. The importance of asymmetric hydrogenation in both academia and industry contributed to two of its pioneers — William Standish Knowles and Ryōji Noyori — being awarded one half of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

A diffusion-limited enzyme catalyses a reaction so efficiently that the rate limiting step is that of substrate diffusion into the active site, or product diffusion out. This is also known as kinetic perfection or catalytic perfection. Since the rate of catalysis of such enzymes is set by the diffusion-controlled reaction, it therefore represents an intrinsic, physical constraint on evolution. Diffusion limited perfect enzymes are very rare. Most enzymes catalyse their reactions to a rate that is 1,000-10,000 times slower than this limit. This is due to both the chemical limitations of difficult reactions, and the evolutionary limitations that such high reaction rates do not confer any extra fitness.

Jeremy Randall Knowles was a professor of chemistry at Harvard University who served as dean of the Harvard University faculty of arts and sciences (FAS) from 1991 to 2002. He joined Harvard in 1974, received many awards for his research, and remained at Harvard until his death, leaving the faculty for a decade to serve as Dean. Knowles died on 3 April 2008 at his home.

Thomas C. Bruice was a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at University of California, Santa Barbara. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1974. He was a pioneering researcher in the area of chemical biology, and is one of the 50 most cited chemists.

Gordon G. Hammes is a distinguished service professor of biochemistry, emeritus, at Duke University, professor emeritus at Cornell University, and member of United States National Academy of Sciences. Hammes' research involves the study of enzyme mechanisms and enzyme regulation.

Borinic acid, also known as boronous acid, is an oxyacid of boron with formula H

2BOH. Borinate is the associated anion of borinic acid with formula H

2BO−

; however, being a Lewis acid, the form in basic solution is H

2B(OH)−

2.

Supramolecular catalysis is not a well-defined field but it generally refers to an application of supramolecular chemistry, especially molecular recognition and guest binding, toward catalysis. This field was originally inspired by enzymatic system which, unlike classical organic chemistry reactions, utilizes non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, cation-pi interaction, and hydrophobic forces to dramatically accelerate rate of reaction and/or allow highly selective reactions to occur. Because enzymes are structurally complex and difficult to modify, supramolecular catalysts offer a simpler model for studying factors involved in catalytic efficiency of the enzyme. Another goal that motivates this field is the development of efficient and practical catalysts that may or may not have an enzyme equivalent in nature.