Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall sandwiched between an inner cytoplasmic cell membrane and a bacterial outer membrane.

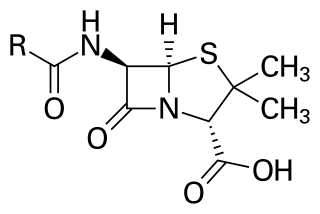

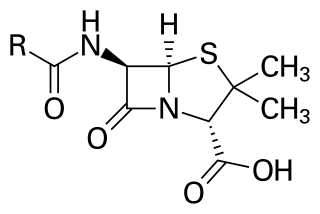

Penicillins are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from Penicillium moulds, principally P. chrysogenum and P. rubens. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum using deep tank fermentation and then purified. A number of natural penicillins have been discovered, but only two purified compounds are in clinical use: penicillin G and penicillin V. Penicillins were among the first medications to be effective against many bacterial infections caused by staphylococci and streptococci. They are still widely used today for different bacterial infections, though many types of bacteria have developed resistance following extensive use.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, also known as gonococcus (singular), or gonococci (plural), is a species of Gram-negative diplococci bacteria isolated by Albert Neisser in 1879. It causes the sexually transmitted genitourinary infection gonorrhea as well as other forms of gonococcal disease including disseminated gonococcemia, septic arthritis, and gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum.

Neisseria is a large genus of bacteria that colonize the mucosal surfaces of many animals. Of the 11 species that colonize humans, only two are pathogens, N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae.

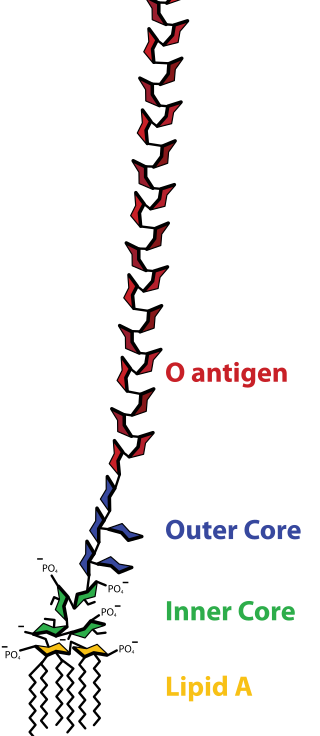

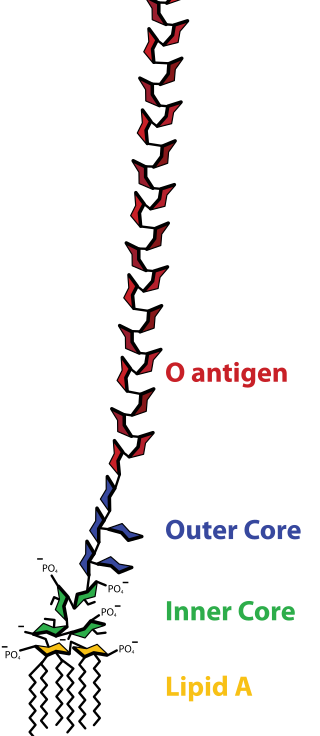

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are large molecules consisting of a lipid and a polysaccharide that are bacterial toxins. They are composed of an O-antigen, an outer core, and an inner core all joined by covalent bonds, and are found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli and Salmonella. Today, the term endotoxin is often used synonymously with LPS, although there are a few endotoxins that are not related to LPS, such as the so-called delta endotoxin proteins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis.

MeNZB was a vaccine against a specific strain of group B meningococcus, used to control an epidemic of meningococcal disease in New Zealand. Most people are able to carry the meningococcus bacteria safely with no ill effects. However, meningococcal disease can cause meningitis and sepsis, resulting in brain damage, failure of various organs, severe skin and soft-tissue damage, and death.

The bacteria capsule is a large structure common to many bacteria. It is a polysaccharide layer that lies outside the cell envelope, and is thus deemed part of the outer envelope of a bacterial cell. It is a well-organized layer, not easily washed off, and it can be the cause of various diseases.

Neisseria meningitidis, often referred to as the meningococcus, is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia, a life-threatening sepsis. The bacterium is referred to as a coccus because it is round, and more specifically a diplococcus because of its tendency to form pairs.

A diplococcus is a round bacterium that typically occurs in the form of two joined cells.

Meningococcal disease describes infections caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis. It has a high mortality rate if untreated but is vaccine-preventable. While best known as a cause of meningitis, it can also result in sepsis, which is an even more damaging and dangerous condition. Meningitis and meningococcemia are major causes of illness, death, and disability in both developed and under-developed countries.

Elizabethkingia meningoseptica is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium widely distributed in nature. It may be normally present in fish and frogs; it may be isolated from chronic infectious states, as in the sputum of cystic fibrosis patients. In 1959, American bacteriologist Elizabeth O. King was studying unclassified bacteria associated with pediatric meningitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, when she isolated an organism that she named Flavobacterium meningosepticum. In 1994, it was reclassified in the genus Chryseobacterium and renamed Chryseobacterium meningosepticum(chryseos = "golden" in Greek, so Chryseobacterium means a golden/yellow rod similar to Flavobacterium). In 2005, a 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree of Chryseobacteria showed that C. meningosepticum along with C. miricola were close to each other but outside the tree of the rest of the Chryseobacteria and were then placed in a new genus Elizabethkingia named after the original discoverer of F. meningosepticum.

Capnocytophaga is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria. Normally found in the oropharyngeal tract of mammals, they are involved in the pathogenesis of some animal bite wounds and periodontal diseases.

Cefodizime is a 3rd generation cephalosporin antibiotic with broad spectrum activity against aerobic gram positive and gram negative bacteria. Clinically, it has been shown to be effective against upper and lower respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, and gonorrhea. Cefodizime is a bactericidal antibiotic that targets penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) 1A/B, 2, and 3 resulting in the eventual death of the bacterial cell. In vivo experimental models of infection showed that bacterial clearance by this drug is at least as effective compared with other 3rd generation cephalosporins. It has similar adverse effect profile to other 3rd generation cephalosporins as well, mainly being limited to gastrointestinal or dermatological side effects.

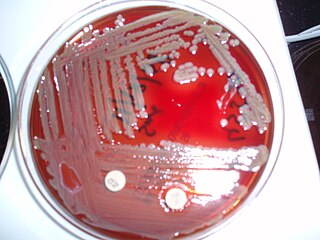

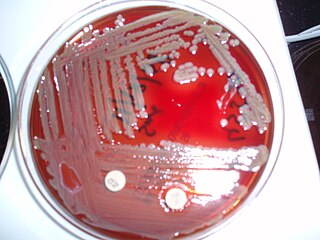

Thayer–Martin agar is a Mueller–Hinton agar with 5% chocolate sheep blood and antibiotics. It is used for culturing and primarily isolating pathogenic Neisseria bacteria, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis, as the medium inhibits the growth of most other microorganisms. When growing Neisseria meningitidis, one usually starts with a normally sterile body fluid, so a plain chocolate agar is used. Thayer–Martin agar was initially developed in 1964, with an improved formulation published in 1966.

Neisseria lactamica is a gram-negative diplococcus bacterium. It is strictly a commensal species of the nasopharynx. Uniquely among the Neisseria they are able to produce β-D-galactosidase and ferment lactose.

Gonococcemia is a rare complication of mucosal Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection, or Gonorrhea, that occurs when the bacteria invade the bloodstream. It is characterized by fever, tender hemorrhagic pustules on the extremities or the trunk, migratory polyarthritis, and tenosynovitis. It also rarely leads to endocarditis and meningitis. This condition occurs in 0.5-3% of individuals with gonorrhea, and it usually presents 2–3 weeks after acquiring the infection. Risk factors include female sex, sexual promiscuity, and infection with resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. This condition is treated with cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone antibiotics.

IgA protease is an enzyme. This enzyme catalyses the following chemical reaction[reaction equation needed]

Neisseria cinerea is a commensal species grouped with the Gram-negative, oxidase-positive, and catalase-positive diplococci. It was first classified as Micrococcus cinereus by Alexander von Lingelsheim in 1906. Using DNA hybridization, N. cinerea exhibits 50% similarity to Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

The NYC medium or GC medium agar is used for isolating Gonococci.

Neisseria polysaccharea was described in 1983 and is characterized by its ability to produce acid from glucose and maltose and polysaccharide from sucrose. It is nonpathogenic. Strains of this species were previously identified as nontypable strains of N. meningitidis. Strains of N. polysaccharea also may have been misidentified previously as N. subflava because their ability to produce polysaccharide from sucrose was not determined. Other Neisseria species have been be misidentified as N. polysaccharea by acid production tests and supplemental tests.