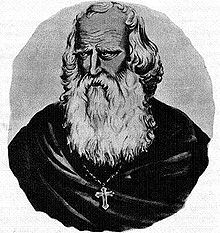

Gregory the Illuminator was the founder and first official head of the Armenian Apostolic Church. He converted Armenia from Zoroastrianism to Christianity in the early fourth century, making Armenia the first state to adopt Christianity as its official religion. He is venerated as a saint in the Armenian Apostolic Church and in some other churches.

Isaac or Sahak of Armenia was the catholicos of the Armenian Church from c. 387 until c. 438. He is sometimes known as Isaac the Great or Sahak the Parthian in reference to his father's Parthian origin. He was the last Armenian patriarch who was directly descended from Gregory the Illuminator, who converted the Kingdom of Armenia to Christianity in the early fourth century and became the first head of the Armenian Church. He supported Mesrop Mashtots in the creation of the Armenian alphabet and personally participated in the translation of the Bible into Armenian.

Mamikonian, or Mamikonean, was an Armenian aristocratic dynasty which dominated Armenian politics between the 4th and 8th centuries. They were the most notable noble house in Early Christian Armenia after the ruling Arsacid dynasty and held the hereditary positions of sparapet and dayeak, allowing them to play the role of kingmaker for the later Armenian kings. They ruled over extensive territories, including the Armenian regions of Tayk, Taron, Sasun, and Bagrevand, among others. The Mamikonians had a reputation as supporters of the Roman Empire in Armenia against Sasanian Iran, although they also served as viceroys under Persian rule. Their influence over Armenian affairs began to decline at the end of the 6th century and suffered a final, decisive blow after a failed rebellion against Arab rule over Armenia in 774/75.

Pap was king of Armenia from 370 until 374/375, and a member of the Arsacid dynasty. His reign saw a short, but notable period of stabilization after years of political turmoil. Although Armenia had been conquered and devastated by the Sassanid king Shapur II in 367/368, Pap was restored to the throne at a young age with Roman assistance in 370. Early in his reign, Armenia and Rome won a joint victory over the Persians at the Battle of Bagavan, and some former territories of the kingdom were reconquered by the efforts of his sparapet (general-in-chief) Mushegh Mamikonian. Although Pap's reign began with a reconciliation of the monarchy, nobility and church, his relations with the church soon deteriorated. Pap allegedly had the Patriarch of Armenia, Nerses I, poisoned, although some later historians doubt this narrative. Pap also eventually ran afoul of the Romans, who suspected him of colluding with the Persians. The emperor Valens unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate him in 373/374, but ultimately succeeded in having him killed in 374/375. He was succeeded by his nephew Varazdat as king.

Dvin was a large commercial city and the capital of early medieval Armenia. It was situated north of the previous ancient capital of Armenia, the city of Artaxata, along the banks of the Metsamor River, 35 km to the south of modern Yerevan. It is claimed it was one of the largest cities east of Constantinople prior to its destruction by the Mongols in the 13th century, but with an overall area of approximately 1 km2, it was far smaller than many of the great cities of Asia.

Varazdat was the king of Arsacid Armenia from 374/375 until 378. He was installed on the throne by the Roman emperor Valens after the assassination of his kinsman King Pap.

Khosrov III the Small was the king of Arsacid Armenia c. 330–338/339.

Arshak II, also written as Arsaces II, was an Arsacid prince who was King of Armenia from 350 until c. 364/367. Although Arshak's reign opened with a period of peace and stability, it was soon plagued by his conflicts with the Armenian church and nobility, as well as a series of wars between Rome and Persia, during which the Armenian king teetered between the warring sides. Arshak participated in the Roman emperor Julian's ill-fated campaign against Persia; after the consequent Perso-Roman Treaty of 363, Armenia was left to fend for itself against a renewed attack by the Persian king Shapur II. Faced with defections and rebellions among the Armenian nobility, Arshak was lured to Persia for peace negotiations with Shapur, after which he was imprisoned in the Castle of Oblivion in Khuzistan and is said to have committed suicide in captivity. Arshak's reign was followed by the conquest and devastation of Armenia by the Persians, although his son and heir Pap managed to escape and later ascended to the Armenian throne with Roman assistance.

Tiran known also as Tigranes VII, Tigranes or Diran was an Armenian prince who served as a Roman client king of Arsacid Armenia from 339 until 350. He was a contemporary of and is associated with the life of Sarkis the Warrior and his son, Martiros.

Christianity first spread to Armenia prior to the official adoption of the faith in the early fourth century, although the details are obscure. In the early fourth century, the Kingdom of Greater Armenia adopted Christianity as its state religion, becoming the first state to do so. The Arsacid king of Armenia at the time, Trdat, was converted by Gregory the Illuminator, who became the first head of the Armenian Church. The traditional date for the conversion of Armenia is 301, although many alternative dates have been proposed by scholars. While Armenia's church structure was established at this time, it took longer for Christianity to fully take root in the country. The greatest progress came after the invention of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop Mashtots and the translation of the Bible and liturgy into Armenian in the fifth century.

Sahak I was a catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church and the first of several catholicoi during the Albaniosid Dynasty in fourth century.

Mushegh I Mamikonian was an Armenian military officer from the Mamikonian family who occupied the hereditary office of sparapet (generalissimo) of the Kingdom of Armenia under the Arsacid kings Pap and Varazdat. He took part in the Armenian resistance against the forces of the Sasanian monarch Shapur II, notably taking part in the Battle of Bagavan, where the Iranian forces were defeated. He was the regent of Armenia under the young and inexperienced Varazdat, who eventually suspected him of posing a danger to his rule, and thus had him executed, in 377/8.

Arshak III, also known as Arsaces III or Arsak III was an Arsacid prince who served as a Roman client king of Armenia from 378 until 387. Arshak III is often known as the last serving Roman client king of Armenia. During his reign, the part of Armenia that Arshak III governed was under Roman rule from the Peace of Acilisene.

Husik I or Yusik was hereditary patriarch of the Armenian Church of the Gregorid line during the reign of the Arsacid king Tiran. He was the son of Vrtanes I, his predecessor as patriarch, and the grandson of Gregory the Illuminator, the founder of the Armenian Church. His patriarchate is dated to 341–347. He came into conflict with the monarchy and was assassinated on the king's orders. He is venerated as a saint in the Armenian Church.

Vramshapuh was a noble of the Arsacid dynasty who served as the Sasanian client king of Armenia from 389 until his death in 414. He is mainly remembered for presiding over the creation of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop Mashtots.

The Battle of Bagavan or the Battle of Vagabanta was fought in 371 near the settlement of Bagavan, in the district of Bagrevand in Greater Armenia, between a joint Roman-Armenian force and a Sassanid army, with the Romans and Armenians emerging victorious. It is recorded by the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, as well as the Armenian historian Faustus of Byzantium.

Anak the Parthian was a Parthian noble who, according to the Armenian tradition, was the father of Gregory the Illuminator, who converted Armenia to Christianity in the early fourth century. Anak is said to have killed King Khosrov of Armenia at the incitement of the Sasanians, leading to his own murder and the extermination of his family, except for the child Gregory, who was saved and taken to Roman territory. The details and historicity of this account have been debated by historians.

Khosrov IV, called Khosrov III in some sources, was a noble of the Arsacid dynasty who served as the Sasanian client king of Armenia from 384/385 until 389 and again from 414 to 415 or 417 to 418. He was appointed king of Armenia by the Sasanian king, who gave Khosrov his sister in marriage. During his reign, Armenia was partitioned into Roman and Sasanian sectors with the Peace of Acilisene in 387. Khosrov reigned in the eastern, Sasanian part, while his relative Arshak III reigned in the western, Roman part. He reigned for about five years before being denounced by the Armenian nobility for conspiring with Rome and deposed and deported to Iran. He was briefly restored to the throne after the death of his brother and successor Vramshapuh, but he died not long after that.

The Castle of Oblivion, also known as the Prison of Oblivion or the Fortress of Oblivion, was a castle and political prison of the Sasanian Empire located in Khuzestan in southwestern Iran. According to the Buzandaran Patmutʻiwnkʻ and Procopius' Persian War, the name referred to the fact that it was forbidden to mention the name of the castle or its prisoners. It may be identifiable with the fortress of Agabana mentioned by Ammianus Marcellinus as the place of Arshak II's imprisonment. According to Claudia Ciancaglini and Giusto Traina, the Armenian form berd Anush is a borrowing from an unattested Middle Persian name which may be reconstructed as *anōš bard. The form Anyush is a later reinterpretation or Armenianization of the original word, identifying it with the common word anyush 'forgotten'. Ciancaglini argues that the original meaning of the name was not 'Castle of Oblivion'—a sense derived from the Armenian etymological reinterpretation—but rather 'immortal, imperishable fortress'.

Buzandaran Patmutʻiwnkʻ was a history of 4th-century Armenia, presumably composed in the 470s. The author of the work is unknown. Until recently it had been assumed that it was written by a certain Faustus ; however, his existence is now disputed. Nina Garsoïan argues that the author was an anonymous cleric who was sympathetic to the nobility and had some competence in preaching. The book starts with the death of Gregory the Illuminator in 331 and concludes with the partition of Armenia between Iran and Rome in 387.